Authors:

Assist. Prof. Hichem Derradji, University of Biskra, Algeria, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1767-6256

Dr. Ali Madouni, University of Biskra, Algeria, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7575-8607

DOI: https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.23.3.3

Review paper

Received: March 10, 2022

Accepted: September 5, 2022

Abstract

This study aims to highlight the significant role played by the escalating security policies in obstructing development efforts in the African continent, despite the tremendous financial support of international donor institutions with the aim of advancing development in the continent; the process of imparting security to the internal scene in these countries remained for decades diverting all those allocated budgets towards

the sectors of militarisation, armament and security, by using a discourse that carries within its core all forms of existential threat, such as promoting the threat of international terrorism, which allows these countries to use exceptional methods in dealing with such dangers, while ensuring the international approval of the donors involved in these policies by virtue of the advantages they benefit from that are related to the other side of the hidden agenda of the process of securitisation of development, which provides them with a guarantee of the continuation of their economic interests.

Keywords: Securitisation, Armaments, Militarization, development, Africa.

Introduction

For decades, the African continent witnessed organized looting of its natural resources and capabilities by the major colonial powers. This region is rich in its various resources, and African labor was vital fuel for the industrial revolution in Europe during the nineteenth century.

With the emergence of the liberation waves during the middle of the last century, most African states gave development projects the highest priority in their political agenda. They tried to work on the provision of all requirements for the success of these projects. Post-colonialism - in addition to the emergence of many problems related to the borders inherited from colonialism at the time, are all factors that forced these newly independent states to change their priorities towards the security sectors and the resulting armament and militarization projects. However, the abrupt shift did not eliminate the traditional interest of the continent in development, with many voices within the continent working to defend the development option until the events of September 11, 2001, which abruptly changed the course of events as terrorist attacks on the two World Trade Towers in the United States of America which led this latter to declare a global war on terrorism.

In order to ensure the success of this new security approach, all parties, whether major Western countries, donors, or African governments, used the discourse of securitization. This discourse implies the existence of an existential threat that affects the physical or moral survival of a security reference, an individual, a group, or a state. Alternatively, identity and the process of securitizing an issue aim to legitimize politicians to international institutions and conclude exceptional arrangements to secure the threatened entity from various dangers. The main objective of the securitization process in Africa was to give legitimacy to the armaments and militarisation projects launched by the various successive governments in the region, which pivotally affected the path of faltering development for many years.

Methodology

We will try to theoretically address many of the problems associated with the process of taking over the international development aid and changing its course towards the military and security sectors, depending on the theory of securitization for several considerations, foremost of which is the theory's superior ability to analyze and explain the mechanisms of the process of securitizing development on the continent. This theory's basic premise is based on an attempt to negate the objective condition of security and consider it a result of a set of practices and discourses. It leads us theoretically to the mechanisms that transform the question from a political viewpoint to a security problem. The latter is used by promoting the existence of an existential danger that targets the fundamental policy of the state and society, including the establishment of work to prepare public opinion to tolerate violations that the securitization process may cause. These are the violations that international donors and African governments are trying to conceal under the state of exception, which has grown in popularity in the aftermath of 2001, emphasizing the possibility of addressing a variety of concerns beyond the scope of its standard policy.

Securitization of development: a cognitive entry

Development is a critical issue that has become increasingly entwined with security concerns. Development securitization policies became visible during the 1990s, especially regarding the emergence of internal armed conflicts in the Third World Countries and increased crime and violence in developing economies in urban areas. In the same context, policymakers and researchers attributed the phenomenon of armed conflict and crime to economic inequality, underdevelopment, and the absence of development. This causal link was reinvented after11 September 2001 to provide scientific explanations for the phenomenon of terrorism. After that, it constituted a fundamental shift in the relationship between development and security, directly manifested in the development aid provided by Western countries and international donor organizations to Africa's poorest countries.

Western aid and international development have undergone many changes, gradually shifting towards focusing on the policies of securitization and militarization, especially in the hot spots in the so-called “global war on terrorism." Despite the different interpretations of this process, there seems to be a widespread agreement on two related issues: first, that securitization has had a harmful and undesirable impact on key development areas such as social life, human rights, and governance reform, second that the security agenda in the global war on terrorism has been set and promoted by Western actors.

These parties believe that weak governments with complete control over their lands will effectively fuel terrorism. Thus, supporting these weak governments with security and military aid and diverting development budgets towards armament and security sectors becomes a top priority.

Tony Blair, the former British Prime Minister, stated in 2004: 'We know that poverty and insecurity lead to weak states that can serve as safe havens for terrorists and other criminals... Al-Qaeda had already been active before September 11, 2001. They have and continue to have bases in Africa; they hide in regions that are difficult for weak governments to manage, and from there, they plot their next strikes, which might take place anywhere in the world, including Africa.'

They went beyond being just an attempt to achieve a set of security goals for Western donor countries at the expense of development. Many ruling political regimes in Africa have helped this trend, as it is a trend that intersects with their narrow interests, despite its intense conflict with the interests of poor peoples and the various development requirements on the continent. This method ensures their longevity and continuity as long as they protect Western interests in their countries. Many voices have rejected the securitization process, especially in light of its policies aiming to integrate official development assistance into the national security framework. In contrast, many local organizations in Africa have expressed their concerns about prioritizing security at the expense of humanitarian goals, which, according to them, undermines development efforts and diverts money from poverty-reduction projects elsewhere; they attempt to argue that assistance used to prevent terrorism will not benefit the poorest in need. However, they are more likely to be recruited by terrorist organizations. Consequently, the results may contradict the donors' expectations, as the African opposition and jurists have increasingly noted. The United States has raised the value of its foreign assistance to Africa very clearly after September 11, 2001, and it raises many questions about the hidden goals behind this accelerating increase. (See Table No. 1).

Table. 1. U.S. Development assistance to selected African Countries 1998-2005 (Thousand Dollars).

|

Angola

|

Djibouti

|

Eritrea

|

Ethiopia

|

Kenya

|

Mali

|

Nigeria

|

Years

|

|

13,000

|

0

|

11,200

|

42,885

|

19,500

|

37,500

|

7,000

|

1998

|

|

14,019

|

0

|

10,175

|

42,702

|

20,470

|

35,372

|

16,917

|

1999

|

|

9,996

|

0

|

8,827

|

39,738

|

31,373

|

35,248

|

37,500

|

2000

|

|

9,963

|

0

|

10,119

|

40,647

|

33,199

|

33,679

|

54,304

|

2001

|

|

11,174

|

0

|

10,908

|

43,257

|

41,110

|

36,176

|

58,034

|

2002

|

|

12,365

|

2,000

|

10,160

|

50,438

|

51,398

|

40,402

|

71,296

|

2003

|

|

11,300

|

0

|

6,290

|

52,763

|

44,110

|

38,596

|

56,151

|

2004

|

|

11,674

|

0

|

6,386

|

54,720

|

44,133

|

34,767

|

59,314

|

2005

|

|

Rwanda

|

Somalia

|

South Africa

|

Sudan

|

Tanzania

|

Uganda

|

Years

|

|

7,500

|

4,000

|

70,100

|

0

|

19,700

|

44,764

|

1998

|

|

14,755

|

1,500

|

54,816

|

0

|

21,951

|

49,106

|

1999

|

|

16,120

|

0

|

46,167

|

0

|

23,822

|

49,012

|

2000

|

|

4,164

|

3,000

|

50,027

|

4,500

|

21,103

|

49,878

|

2001

|

|

18,502

|

2,767

|

57,708

|

11,131

|

24,808

|

59,724

|

2002

|

|

22,296

|

3,372

|

62,958

|

18,871

|

37,809

|

68,297

|

2003

|

|

18,160

|

999

|

52,006

|

61,763

|

28,200

|

61,642

|

2004

|

|

18,527

|

986

|

50,800

|

81,000

|

26,988

|

54,744

|

2005

|

Source: (Rhetoric and Reality: US-Africa Relations since 9/11, 2008)

All countries classified in the reports of the U.S. State Department as strategic allies in the war on terrorism, except for Eritrea, witnessed an increasing amount of aid. However, the largest share of this development aid after 2001 was obtained by Sudan, whose funding increased by 94.4 percent, a country classified in three successive reports of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on global terrorism as one of the seven state sponsors of terrorism. Undoubtedly, the increase in funding reflects U.S. security concerns within Sudan.

In his 2015 speech, former European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker announced the creation of the European Emergency Trust Fund for Africa. One billion is intended to support 117 aid programs, focusing on economic development, job creation, governance, food security, health care, and migration management. However, the financing allocations to the Fund have witnessed a significant increase; according to the latest reports issued by the auditors for 2018, 4,1bil€, including three 7bil€, from the European Union budget and European development funds. The Fund currently supports 26 African countries in three regions: Lake Chad and the Sahel, the Horn of Africa, and North Africa.

According to Ms. Bettina Jakobsen, a member of the European Court of Auditors, the Fund's primary goal is to address the issue of migration, and she criticized the Fund's performance after three years of work by saying:

'If we consider the unprecedented challenges and the size of the budget presented, the Fund should be more focused and direct its supportive efforts towards specific actions capable of addressing migration.’

The follow-up to the aid programs provided by the Fund to the African countries benefiting from these programs leads us to emphasize the security importance of this aid, away from all the declared developmental reasons. Most African countries are mainly considered source countries for illegal immigration and are a growing concern for decision-makers and the European political class.

The war on terrorism: The best pretext to justify securitization

Even though Africa is home to many terrorist organizations, practically all of them belong to two major organizations: Al-Qaeda and Daesh, where all other sub-organizations usually rush to hide under the pretext of one of these two organizations. These are classified under the international terrorist organizations that Western countries are working to combat by providing material and logistical support to African governments.

Throughout the fifth and sixth sessions of the Sixth Committee meeting of the 74th session of the United Nations, this prompted the delegates of some African countries to invite the attendees to help them financially in the fight against terrorist groups. Many African governments have waged their war on terrorism. At the same time, the delegate of Burkina Faso stressed the seriousness of the security situation in West Africa; he called on bilateral and multilateral partners to provide more support. In contrast, the delegate of Cameroon said: 'The danger and threat cannot be addressed by a country alone; rather, there should be concerted efforts by many parties.'

On this basis, Western countries and donors are working to support these African governments to eliminate these organizations through several projects supervised directly or within the framework of aid provided by international institutions. (See Table No. 2)

Table. 2. U.N. Projects to strengthen counterterrorism

|

Amount

|

Region/Country

|

Project name

|

Year of

Approval

|

|

$921,880

|

Group of Five for the Sahel (Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger,

and Chad)

|

Supporting the regional efforts of the G5 Sahel countries in combating

terrorism and preventing violent extremism

|

2016

|

|

$1,014.818

|

the Sahel and North Africa

|

Strengthening the capabilities of African countries to combat the use

of the Internet for terrorist purposes

|

2017

|

|

$694,540

|

SouthernAfricaRegion

|

Supporting SADC Countries to Strengthen the Rule of Law-Based Criminal

Justice Response to Preventing Terrorism and Violent Extremism

|

2017

|

|

$2,016,522

|

Djibouti

|

Strengthening forensic capabilities of Djiboutian law enforcement

entities in order to bring terrorists to justice

|

2017

|

Source: (United Nations Peace and Development Trust Fund, 2020)

Meanwhile, France, Germany, and other donors led an international alliance for the Sahel. It received the support of the African Development Bank, the World Bank, and the United Nations Development Programme. The alliance's portfolio currently includes more than 800 approved, ongoing, or understudy projects with a value of 11,6bil€of which alliance members invested nearly €1,9 bil€in the G5 Sahel countries during 2018.

As for the United States of America, in its strategy to combat terrorism, it relied on a soft fight against terrorism, an idea inspired by the Soft Power Theory of Joseph Nye. On this basis, after11 September 2001, the American administration launched several support projects in Africa in order to besiege terrorism and dry up its sources, the most important of which can be highlighted in the:

- Pan Sahel Initiative 2002:

The United States of America put forward the African Sahel Initiative with West African countries (Mali, Mauritania, Chad, Niger) in November 2002, after which the State Department allocated financial aid worth 7,75 mil US$ aimed at strengthening the military capabilities of these countries, through training operations, in addition to the participation of Units of the U.S. Special Forces and the Navy that are in joint operations with the local armed forces.

- Trans-Saharan Counter-Terrorism Partnership Initiative (TSCTP) 2005:

The partnership is a multi-faceted, multi-year U.S. strategy between the United States of America and many African countries (Algeria, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Tunisia). The partnership aims to build resilient institutions capable of preventing counterterrorism in comprehensive and long-term ways by working to enable partner countries to provide effective and accountable security and judicial services that allow for strengthening citizens' cooperation with and trust in law enforcement agencies, in addition to developing institutions concerned with combating terrorism such as border security, prison security, and reintegration efforts.

- U.S. Military Command AFRICOM 2008

AFRICOM was established on6 February 2007 by U.S. President George W. Bush. It officially entered service on October 01, 2008, as a new security agency responsible for all African countries except for Egypt, which remains under the supervision of the Central Command. The leadership has provided significant financial assistance over the past few years, supporting stability and security in West Africa and the Sahel region.

The war on international terrorism has constituted a powerful excuse for political actors inside and outside the continent to explain resorting to securitization, especially if we knew that the war gives the superior ability to invoke the state of exception and find legal justifications for improper behavior.

The hidden agenda of securitizing development in Africa

Despite the clarity of the stated reasons behind which donors and African governments try to hide, there are many other hidden reasons that theorists of Copenhagen School for Security Studies call the hidden agenda, as this agenda is divided according to the gains of each party into two main parts. The first is tied to the agendas of local governments seeking an exceptional circumstance to legitimize their continued rule other than democratic legal norms. In contrast, the second is related to donors' agendas seeking to achieve both security and economic aims concurrently.

For African governments, the state of emergency is the perfect tool to undermine democracy under the (pretext) of constitutional legitimacy. It is a good argument for why more power is needed. Why do power holders care about human rights, legislative restrictions, or other institutions while the country is under threat or attack? Thus, states of emergency can help dismantle democracy and undermine the resistance to its demise. The opposition can easily be described as unpatriotic for its defiance of the government when the state is endangered and requires unity.

An authoritarian tendency grows when official institutions are disrupted and all powers are concentrated in the president's hands, especially in the absence of rules, regulations, exceptions, and emergency states. In many countries, constitutions stipulate the necessity of resorting to emergency measures in exceptional cases without legislation or legalization accompanying them or even without temporal control of the situation. This made it exceed thirty years in some African countries. All African countries have suffered authoritarian rule under the pretext of emergency laws in exceptional circumstances endangering the state and its institutions, whether during internal ethnic conflicts that have remained a feature of African state-building or during the global war on terrorism by the USA after11 September 2001.

In this context, statistics and data indicate that more than two-thirds of the continent's countries live under a state of emergency; African citizens have experienced this state since independence until today, which is more complex than usual. Many African citizens still live under this state with its consequences, from suppression and violation of public freedoms to restrictions on development and the absence of democracy.

The search for the exceptional case and hiding behind emergency laws express the reality of democracy and ill democracy in the continent. It represents a good argument for staying in power without developing legitimacy. Despite their failure to achieve development, most governments are still hiding behind security legitimacy and their war on terrorism and organized crime, which entitles them to their people and international public opinion to dispose of their budgets and the loans they obtain to serve their interests.

The hidden agenda is not limited to achieving the interests of local governments in Africa only and many of the donors' economic interests who contribute to the securitization process to ensure their interests in the continent. The military spending of African countries comes at the top of the hidden agenda of the donors, as the process of securitization requires more flows of arms that the major countries are working to provide to these countries.

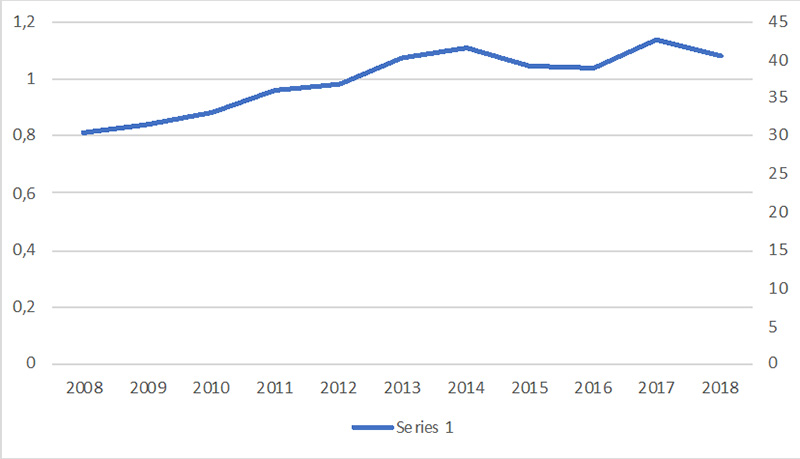

Military spending in Africa in 2017 amounted to about 42,6bilUS$, while the total spending from 2008 to 2018 amounted to 409,3bilUS$. An ascending graph confirms the increasing governmental trend in the continent towards armament and attention to the military aspects and modernizing the armies despite the global economic crisis and its various repercussions on most African economies, which approved many austerity measures to confront them. (See Figure No. 01)

The graph in Figure 01 indicates an increasing escalation of military spending on the African continent from 2008 (to)2017, with a modest recession that did not last long until it rose again, quickly surpassing the effects of the economic crisis. However, this rapid recovery raises many questions about the sources of financing these huge deals in light of the lack of liquidity associated with the decline in oil prices. In the same context, the list of the largest arms suppliers in Africa between 2013-2017 recorded the United States of America, Russia, France, Germany, China, the United Kingdom, Spain, Israel, Italy, and the Netherlands. Most of these countries are among Africa's leading suppliers of loans and aid; hence, the securitization process is more evident in this element of the donors' covert objective.

Fig.1. Military expenditure (graph) in Africa (2008-2018).

Source: Prepared by researchers based on Arms, Disarmament, and International Security reports issued by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (YEARBOOK 2018 and 2019)

This agenda mainly aims to achieve a set of strategic goals for the donors in the short and long terms, as the increase in military expenses in the African countries receiving aid reflects an extensive Western program that works to recover aid funds on the one hand and secure oil supplies on the continent through the use of local armies in guarding significant companies operating in the continent.

The role of securitization discourse in controlling public opinion

The process of securitization development in the African continent stems from the strength of the discourse used. However, when searching the impact and importance of discourse, it seems appropriate to start by asking about the importance of words and language, which was answered by Richard Jackson when he said: 'Words are never neutral, they are not. They not only describe the world, but they also help to make the world.

The use of binary terms, the foundational nature of language, emotional connections, and historical ramifications of particular terms and signs; make discourse a powerful tool loaded with value. In this position, discourse must be seen as a synonym for power. Michel Foucault argues that the entire systems in a society decide the types of discourse that this society accepts and makes accurate. Such discourses are usually produced by a few significant political and economic bodies (the university, the army, and the media.

After September 11, 2001, the security discourse contributed to securitization in Africa that exceeded all perceptions. The discourse's strength over the development discourse is its dual effect on the global and local levels. The United States of America and Western countries have adopted macro securitization, while African countries have been working to rotate the securitization discourse locally. The main features of the discourse of macro securitization have been formed through several critical variables, which can be summarized: First, the rise of the language of dualities; Good/Evil, Civilisation/Barbarism, which in turn gave rise to a new structural division of the world based on; Us/them, explicitly manifested in George Bush Jr's famous speech: "You are with us, or you are with the terrorists." Second, the excessive use of historical parallels through repeated allusions to the Cold War and World War(s), and third, the constant invocation of militarism and exclusion, which made the idea of the war on terrorism, bear a solid and integrated project.

The excessive use of the language of binaries within the discourse of macro securitization gave a general perception that the United States and its allies are leading a battle that does not accept neutrality, which contributed to expanding the scope of their alliance to include a large number of countries in the world. Whoever does not join the alliance is classified within the corresponding alliance. Former British Prime Minister Tony Blair called Africa a scar on the world's conscience.' However, the new and growing interest in the continent is part of the increasing securitization that has gradually shifted all interactions from 'development/humanity' to 'danger/fear/threat.' According to him, the framework of the war on terrorism helped the war on terrorism but did not do much for the continent's accumulated development issues.

Following the dominance of the macro securitization discourse on the international stage, most countries, led by African countries, entered the international war on terrorism and rearranged their priorities in response to the new agenda, with security taking precedence over other projects such as the development democratic trajectories.

Many African countries have adopted the securitization discourse and started to transform their official discourse from mobilizing national capacities and energies for construction and development to a new security discourse based on maximizing the threat and ways to confront it, such as the search for exceptional states, emergency laws, and the overthrow of all norms and laws of defiance, on this basis, in order to confront and eradicate these risks.

This new security discourse is based mainly on exaggerating the threat of terrorist groups through the official speeches of officials or through the various local media, which have occupied the topics of bombings and terrorist operations, the activity of the security forces and the army in combating them, at the forefront of the headlines within them. It creates an abnormal general atmosphere within their societies characterized by fear and insecurity. It pushes them to be more cautious and live in the shadow of mistrust among citizens.

It seems important to emphasize that the combination between the discourse of macro securitization adopted by the major countries and donors and the discourse of securitization at the local level supervised by African governments has led to the complete dominance of security over the development discourse. Donors have become less interested in development than in fighting terrorism, which intersects with the interests of local governments and regimes. The new discourse found an excellent opportunity to impose their survival and continuity away from the opposition. The rhetorical practice and speech act included in the securitization discourse directly aim to control global and local public opinion alike, which gives the international and local political actors that adopt this discourse the legitimacy to use all legitimate and illegal methods in the context of their war on terrorism on the one hand and implement their agenda hidden on the other hand.

In this context, world public opinion constitutes a significant obstacle to the policies of major countries in the African continent, especially with the increasing role of Western media and investigative journalism in uncovering the hidden agenda threads of the declared war on terrorism on the continent. Therefore, the discourse of macro securitization plays a pivotal role in controlling world public opinion to ensure that it does not influence the formulation and implementation of policies used in the continent.

Shifting from speech to militarisation

After the success of great powers and local governments in promoting the discourse of securitization at the international and local levels, the second step comes from the mechanisms of the process, which aims to shift towards more militarisation on the African continent by adopting a new strategy based on transferring development budgets towards various security sectors, and the consequences on that of a significant rise in armaments budgets.

It should be highlighted in this context that a significant shift in development budgets towards the security sectors was realized mainly as a result of the discourse of macro securitization, directly embodied in development aid directed to African countries, which were automatically transformed after the events of the September 11 into security aid targeting armies and security institutions. However, our main subject to discuss is represented in the remainder of development aid that donors failed to retain. Local governments also shifted to security sectors even though their developmental component was preserved in financing contracts.

Several anti-corruption reports indicate that transferring funds from the development sector to the defense sector is followed in many African countries. This is often done in complete secrecy due to what is said about the military sector as different from other parts of the public sector in at least two ways: The first is the need for secrecy in the area of national security, and the second is the highly political nature of spending decisions related to the military sector, especially decisions to acquire arms.

Numerous international studies and reports indicate the significant increase in the size of the budgets of armies, and the growth of arms supply operations in Africa during the past two decades, despite successive economic crises that prompted many African countries to adopt austerity policies that did not seem to include the military sectors that maintained their budgets.

Reinforcement of authoritarianism

The securitization of development in Africa has contributed to many negative results over recent years. The state of exception that accompanied the securitization process at the local level ensured the continuity of the ruling regimes away from democratic requirements, reinforcing the authoritarian tendency in the continent's countries, as well as deepening the state of underdevelopment at all levels due to the developmental decline in contrast to the priority of the security sectors. Due to the continent's direct reliance on foreign aid, the practice of securitization has also contributed to the consolidation of dependence.

Since the early 1990s, democracy and good governance have been central tenets of development discourse and politics, with donors proclaiming the importance of freedom, rights, and accountability for development and prosperity; however, the democratization process seems to have stalled in many African countries. While foreign aid flows freely to some of the continent's most authoritarian and repressive countries, Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Uganda have attracted significant donor support.

In the same context, the governance of four of the ten most essential aid recipients in Africa (Ethiopia, Mozambique, Rwanda, and Uganda) are authoritarian regimes that do not allow democratic participation and criminalize political opposition. At the same time, bilateral and multilateral donors consistently claim to promote democracy, good governance, and human rights on the continent. While democracy in some other countries has a better situation, multiparty elections have become a regular event across the continent. Nevertheless, when describing the results of two decades of democracy promotion, observers conjure weighty terms such as electoral dictatorships, competitive authoritarianism, and hybrid regimes.

In Rwanda, for example, the post-genocide era was characterized by a divided society led by a government that came to power through rebel forces, prompting civil war leader Paul Kagame to initiate a transition to civilian rule. The constitution and later the parliament were agreed upon, beginning with the first cell-level elections (the village sub-committee) in 1999 and provincial-level elections in 2001. However, what happened after that, the dismissal of the prime minister, the banning of the single significant opposition party in the country, the closure of political space, the maintenance of the status of fear, the disappearance of critical voices, the increased muzzling of the press, and the attack on civil society organizations, clearly indicate the faltering path of democratization in the country. Increasingly totalitarian, the course of elections intended to decorate the political facade was preserved. After assuming the presidency of Rwanda by acclamation in 2000 as the victorious leader in the war and then being elected in 2003, 2010, and 2017, Kagame amended the constitution in 2015 to allow him to remain in the presidency for three more periods ending in 2034.

This entire authoritarian tendency did not prevent donors from providing aid to Rwanda. Instead, aid policies have witnessed a noticeable increase during the past two decades and a more vital link to the ongoing securitization operations under the pretext of the threat posed by the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda, which is known to be very active in neighboring Congo, expressing in reverse the role of securitization and foreign aid in deepening authoritarianism in Rwanda.

On the other hand, Knox Chitiyo, Head of the Africa Programme at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), noted: ‘Britain has a lot of financial investments, symbolic and emotional connections in Rwanda, and the irony of this relationship is that Britain needs Rwanda more than the latter.’

Due to the high growth rates in recent years, the flourishing Rwandan economy makes the country's investment environment a magnet for significant countries trying to take advantage of these opportunities.

In Ethiopia, violations of public freedoms and human rights are among the essential features that the successive ruling authorities have not abandoned over the country for decades. They did not disappear with the changes from one political system to another; although their forms and degrees are varied, their situation is under the political system. The current one is witnessing great controversy and an accelerating movement, especially in recent years. Recent political studies have attempted to highlight the Ethiopian political system's authoritarian nature and provide critical insights into the ruling People's Revolutionary Democratic Front's concept of revolutionary democracy and its continuous development policies to control the masses. Perhaps the most significant factor that has helped it in this direction is its increasing ability to attract increasing amounts of international aid in recent years, establishing itself as one of the world's largest recipients of state development assistance, raising numerous questions about the state of extreme contradiction between the absence of democracy and the continuation of the flow of development assistance.

Since the 2005 national elections, the Ethiopian government has enacted restrictive laws and regulations governing the press and civil society organizations, as well as authoritarian measures to combat terrorist threats, such as restricting civil and political rights, which prompted many academics in the context of analyzing the Ethiopian political system to launch many descriptions such as guardianship, the new electoral authoritarianism, and the totalitarian one-party state.

In order to explain this paradox, some observers stressed the ability of the Ethiopian government to manipulate the international development discourse and firmly confront international donors to direct the Official Development Aid (ODA) to meet its political priorities. In contrast, others pointed to donor naivety or ignorance of domestic political dynamics and actual decision-making processes. At the same time, a third trend believes that Western geopolitical priorities in the global war on terrorism outweigh the promotion of human rights and democracy, giving the Ethiopian government a solid card to play in ensuring the continuation of development aid. Other causes are listed, such as the work of the International Assistance Agency, which has selected Ethiopia as an example of the efficiency of its work. The third proposition related to the global war on terrorism is consistent with the declared reasons for the securitization of development in Africa; it pushes us to support this interpretation, especially in light of the practical outcomes of the securitization process at the level of the country's political situation in its aspect related to the dimensions of democracy, human rights, and citizenship.

The situation is not much different in Uganda. On January 29, 1986, Yoweri Museveni was sworn in as president. At that time, he and the popular resistance movement had to find solutions to find quick solutions to the problem of legitimacy after they came to power by force, which prompted Museveni to say at the time: ‘The Ugandan people are a source of sovereignty,’ in an attempt to gain popular support.

However, what happened after that confirms the exact opposite. Uganda was isolated in the non-party system after the president banned political parties from the activity and imposed candidacy in elections based on personal merit. According to the National Resistance Movement, this measure aims to prevent sectarianism, which motivated the president to mention it when he asserted that this system suits Africa better than any other form of Western democracy, claiming that political parties are due to the nature of rural areas. Ugandan society will inevitably turn to play on the strings of ethnicity, region, language, and religion rather than national interests. This remained the case until 2005 when political parties and associations were allowed to operate again.

However, these political parties find in front of them the ruling popular resistance movement, with its solid and undisputed style and practices, as it works to confront any opposition group that poses a real threat to the government with repression, imprisonment, harassment, and systematic intimidation, which prompted many specialists to describe the current Ugandan regime as being a—dictatorship and intolerant.

It adopts more militarisation in dealing with political activists, human rights defenders, and all dissenting voices in the country. The Committee to Protect Journalists recorded a more than tenfold increase in attacks on journalists in Uganda between 2008 and 2011. The security forces were responsible for more than 90 percent of these attacks. Not to mention the shooting of protesters by the security services in several protest stations, such as April 2007, September 2009, and April 2011, the Ugandan regime also responded to what is believed to be strong opposition by arbitrarily closing independent newspapers and radio stations.

In this context, many researchers believe that this continued militarisation of the Ugandan political system would not have occurred without international assistance, especially from Western donors who remained silent about various violations of Museveni's regime. Even more than that, these are due to their direct contribution to strengthening its ability. Since the mid-1990s, donor officials in Washington, London, and Brussels have increasingly promoted the Ugandan regime in neighboring countries and at regional and international levels as a vital counterterrorism provider. Furthermore, peacekeeping solutions have facilitated the military intervention of Ugandan forces in Somalia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and South Sudan.

The Ugandan regime has benefited from significant shifts in the international and regional context since 1986 in order to gradually secure its relations with donors and increase the amount of international support directed towards its military and security forces, as donors have committed to help build and strengthen a military system in Uganda by agreeing to gradual securitization for their relationship with Museveni's government. In doing so, they contributed to creating an increasingly authoritarian state.

Consolidation and dependency

Social anthropologists see dependency theory as one of the most pessimistic theories in social studies. At the macro level, this structural theory stems from a central premise that it is impossible to understand the processes and problems in Africa without looking at the broader socio-historical context of the expansion in Western Europe (industrial and commercial capitalism) and the colonialism of these places by Western economies. According to Walter Rodney, colonialism was not just a system of exploitation. However, its primary objective was to return the profits made in Africa to the so-called homeland, which means, from the perspective of dependency, a process of frequent relocation of the surplus values created by African labor using African resources. On this basis, the development of Europe can be seen as part of the same dialectical processes which led to Africa's backwardness. In other words, Europe's domination of Africa impeded the continent's economic development for five consecutive centuries, during which Europe benefited from its confrontation with Africa.

In the same context, this socio-historical viewpoint supports many economic studies, such as development studies, that have been examined from various perspectives in Africa. Most of them unanimously support the common thesis of underdevelopment, which is an essential principle in the discussion of dependency, especially given the invocation of many concepts and the main variables along the way.

Over the decades, the Nigerian economy has been characterized by escalating inflation, a variable exchange rate exacerbated by currency depreciation, continuous dependency on imports, widespread unemployment, and dilapidated infrastructure, which characterize Nigeria's development challenges due to dependence. The historical impact on the foreign capitalist economies in North America and Europe is primarily due to its distorted post-colonial economic legacy, which response clearly to the fluctuations of the international capitalist system. . It is characterized by a low production base and direct and permanent dependence on foreign markets, foreign aid, and imported technology.

This brought a debate about a variety of issues, including development aid, foreign investments, and foreign loans, as well as the relationship between these issues and adopted development strategies, as well as the growing use of security policies to achieve donor objectives without regard for local development objectives such as poverty reduction, education, and health.

The deteriorating development situation in one of the wealthiest countries in Africa reflects the state of dependency that the political system inherited from colonialism. Even this dependence became an inevitable result of this process, all by drawing security tracks. The process of securitization through foreign aid and foreign loans contributed to its consolidation. A new one completely departs from development paths and is linked to the donors' agenda in combating international terrorism and ensuring their control over its natural resources and wealth.

Deepening the state of underdevelopment

Instead, the matter took another turn. After more than five decades of independence, most African countries have not succeeded in eliminating the state of underdevelopment inherited from colonialism, as their natural resources, the vast human capital, and the diversity of their social and economic background did not help them in this long endeavor. Quite the opposite, the successive political regimes and governments in Africa deepened the backwardness of the continent after its abject failure to achieve the desired development.

This prompted many researchers to find scientific explanations for the state of underdevelopment in Africa, as a broad majority of those saw that the state of backwardness and poor economic performance of Africa was mainly due to the wrong choices made by African leaders, as they are not able to accept new policies compatible with the resources of the continent, on the one hand. They, on the contrary, cannot make their own political decisions, so they are a political weapon for foreign governments and donors, working to protect their interests instead of working on the domestic prosperity of their countries.

The state of underdevelopment that the African continent has reached is an inevitable and natural result of the imbalance between the parties to the tripartite equation - security, militarism, and development - as this equation indicate an inverse relative relationship. On this basis, it is possible to rely on external narratives of African underdevelopment in linking colonialism and the crisis of underdevelopment in post-colonial Africa, especially in light of what we saw previously in the problems of dependency and neo-colonialism. The presence of other civil factors also disrupted development. It contributed to deepening the state of underdevelopment on the continent, as the local ruling class sought for decades behind rent and primitive accumulation of wealth, in addition to the endemic, systematic, and accidental nature of corruption in public life across regions and the impact of this phenomenon on the development of the region.

As a result, the continent is experiencing an underdevelopment crisis due to increasing securitization policies and the marginalization of development favoring security. This is only one of the many manifestations of these policies that Western countries and donors bear in the first place, without overlooking the negative role played by the ruling political elites.

Conclusion

Immediately after the September 11, 2001 attacks, the securitization process on the African continent experienced a remarkable acceleration, as the United States of America and its European allies in the West resorted to using development aid in their war on international terrorism, prompting them to use the discourse of macro securitization to express the significant threat it poses. Terrorism, which later had a significant impact on African political institutions, tended to adopt the same vocabulary at the local level.

The declared reasons for adopting securitization policies on the African continent met, as the major countries, African governments, and regimes agreed on the main goal behind these policies: to fight terrorism. However, the two parties: The principal countries and the African governments, differed in their hidden agenda behind this trend, while the significant countries were discussing achieving several economic goals for the donors, such as recovering the aid money they were paying to these countries through arms deals concluded under the misleading securitization process, in addition to ensuring the security of African oil supplies. The multinational companies on the continent, African governments, and ruling regimes were looking forward to searching for the exceptional state provided by the securitization process, enabling it to continue ruling away from the exorbitant costs of democracy and the peaceful transfer of power.

The securitization process in Africa begins with the dominance of the security rhetoric over the continent's development discourse. The discourse of securitization in this context is divided into two main parts:

The first is related to the discourse of macro securitization launched by the major powers, which aims to prepare targeted public opinion for exploiting development aid to achieve security goals.

While the second is related to the discourse of securitization at the local level, which is launched by governments and ruling regimes in Africa and aims, in turn, to control local public opinion and to implement the securitization agenda exceptionally away from all forms of opposition, so it proceeds to transfer development budgets towards the security and military sectors quickly. And without any objection from donors who were setting many conditions related to democracy and ensuring the disbursement of funds in their development banks before the rhetoric of macro securitization. The securitization of development in Africa has contributed to the formation and worsening of numerous challenges relating to the continent's governance and development systems. It has encouraged securitization policies in the following ways:

- The strengthening of authoritarian tendencies in many countries of the continent, where the exceptional situation imposed by the securitization process affected the path of democratic transition that began at the end of the eighties. The state of emergency in connection with the fight against international terrorism has expanded across the continent, and regimes have used it to target opponents and all voices asking for reform and change.

- Consolidating dependency by linking African economies to development aid and external loans directly contributed to the exacerbation of the indebtedness situation that most of the continent's countries mortgaged to donors, whether states or international institutions, which was then called neo-colonialism in Africa.

- Deepening the state of underdevelopment through increased attention to the security sectors and neglect of development.

Citate:

APA 6th Edition

Derradji, H. i Madouni, A. (2022). The securitisation of development in Africa: causes, mechanism, and consequences. National security and the future, 23 (3), 49-82. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.23.3.3

MLA 8th Edition

Derradji, Hichem i Ali Madouni. "The securitisation of development in Africa: causes, mechanism, and consequences." National security and the future, vol. 23, br. 3, 2022, str. 49-82. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.23.3.3 Citirano DD.MM.YYYY.

Chicago 17th Edition

Derradji, Hichem i Ali Madouni. "The securitisation of development in Africa: causes, mechanism, and consequences." National security and the future 23, br. 3 (2022): 49-82. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.23.3.3

Harvard

Derradji, H., i Madouni, A. (2022). 'The securitisation of development in Africa: causes, mechanism, and consequences', National security and the future, 23(3), str. 49-82. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.23.3.3

Vancouver

Derradji H, Madouni A. The securitisation of development in Africa: causes, mechanism, and consequences. National security and the future [Internet]. 2022 [pristupljeno DD.MM.YYYY.];23(3):49-82. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.23.3.3

IEEE

H. Derradji i A. Madouni, "The securitisation of development in Africa: causes, mechanism, and consequences", National security and the future, vol.23, br. 3, str. 49-82, 2022. [Online]. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.23.3.3

Notes:

1 Bernard Jonathan, "Environmental Security Theories: A Critical Look at an Ambiguous Concept," ( Master's Degre, the University of Quebec in Montreal,2007), 33.

2 Barry Buzan. Ole Waever, Jaap de Wilde, Security: A New Framework for Analysis. (London: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1998) 25.

3 Matt McDonald, " Securitization and the Construction of Security. " European Journal of International Rela-tions, The University of Warwick, 2008, 563-587, https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066108097553.

4 Lars Buur, Steffen Jensen, Finn Stepputat, The Se-curity-Development Nexus: Expressions of Sovereignty and Securitisation in Southern Africa. (Stockholm : Elanders Gotab AB, 2007), 09

5 Lars Buur, Steffen Jensen, Finn Stepputat. Op, cit, 09.

6 Jonathan Fisher, David Anderson, « Authoritarianism and The Securitization of Development in Africa.» International Affairs, The Royal Institute of International Affairs, (2015),131–151, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12190.

7 Lars Buur, Steffen Jensen, Finn Stepputat. Op, cit, 09.

8 Jaroslav Petřík, «Securitisation of Official Develop-ment aid: Analysis of current debate.» International Peace Research Conference, Leuven, Belgium Con-flict Resolution and Peace-Building Commission, (14-19 July 2008), 06.

9 Rhetoric and Reality: US-Africa Relations since 9/11, op cit.

10 European Commission, "The E.U.'s Key Partnership with Africa." The State of The Union In 2017, 03.

11 The E.U. trust fund for Africa: a flexible instrument, but not sufficiently targeted, according to the European Court of Auditors, Obtained:https://www.africa-newsroom.com/press/eu-trust-fund-for-africa-flexible-emergency-tool-but-lacking-focus-say-auditors?lang=fr, Day: 03/25/2020, at 17:15.

12 Ibid.

13 Meetings Coverage And Press Releases, " Dele-gates Call for Critical Financial Support to Combat Terrorist Groups, as Sixth Committee Continues Debate on Eliminating Global Menace. " United Nations, Lookhttps://www.un.org/press/en/2019/gal3594.doc.htm, On 20/20/2020, at 12:20.

14 Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs, "France's action in the Sahel". See https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/politique-etrangere-de-la-france/securite-desarmement-et-non-proliferation/terrorisme-l-action-internationale-de-la-france/l-action-de-la-france-au-sahel/article/l-action-de-la-france-au-sahel, day 04/20/2020, at 12:41.

15 William F.S. Miles, "Deploying Development to Counter Terrorism: Post-9/11 Transformation of U.S. Foreign Aid to Africa". African Studies Review, Vol-ume: 55, Issue: 03, (December 2012), https://www.jstor.org/stable/43904847, 31.

16 Stephen Ellis, " Briefing: The Pan-Sahel Initiative. " African Affairs, Royal African Society, N: 412, (2004), www.jstor.org/stable/3518567,459-464.

17 U.S. Department of State. " Trans-Sahara Counter-terrorism Partnership," Bureau of International Narcot-ics and Law Enforcement Af-fairs:https://www.state.gov/trans-sahara-counterterrorism-partnership/, 05/25/2020, 11:48.

18 Alex Amaechi Ugwuja, " The United States Africa Command (Africom) And Africa's Security in The Twenty-first Century. " Renaissance University Journal of Management and Social Sciences (RUJMASS) Vol: 4, N°: 1, July 2018. 61-84.

19 Anna L Uhrmann, Bryan Rooney, " When Democra-cy Has A Fever: the States of Emergency as a Symp-tom and Accelerator of Autocratization." Working Pa-per, The Varieties of Democracy Institute, Sweden: Department of Political Science, University of Gothen-burg, (2019), https://privpapers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3345155, 11.

20 Armaments, Disarmament and International Securi-ty: Yearbook 2018. SIPRI: Stockholm, 2018,202

21 Ibid, 240.

22 Chris Rossdale, " The Constitutive Effects for Conflict and Insecurity of The Post-9/11 Discourse on Terrorism ". E-International Relations, (June 11, 2009),02, https://www.e-ir.info/pdf/1507

23 Chris Rossdale, op, cit, 02

24 Ibid, 03.

25 Rita Abrahamsen. " Blair's Africa: The Politics of Se-curitization and Fear. " Alternatives: Global, Local, Po-litical 30, no, (2005, January 01),55, https://doi.org/10.1177/030437540503000103.

26 Wuyi Omitoogun, Eboe Hutchful, " Budgeting for the Military Sector in Africa: The Processes and Mecha-nisms of Control. " Stockholm: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, ( 2006), 15.

27 Rita Abrahamsen, " Discourses of democracy, prac-tices of autocracy: shifting meanings of democracy in the aid–authoritarianism nexus."Aid and Authoritarianism in Africa: Development Without Democracy, ed. Tobias Hagmann and Filip Reyntjens(London: Zed Books, 2016), 21.

28 Tobias Hagmann, Filip Reyntjens. " Aid and Authori-tarianism in Sub-Saharan Africa After 1990 ", Aid and Authoritarianism in Africa: Development Without De-mocracy, ed. Tobias Hagmann and Filip Reyntjens (London: Zed Books, 2016), 01.

29 Rita Abrahamsen. " Discourses of democracy, prac-tices of autocracy: shifting meanings of democracy in the aid–authoritarianism nexus. " Op cit, 21.

30 Zoë Marriage, " Aid to Rwanda: unstoppable rock, immovable post. " Aid and Authoritarianism in Africa: Development Without Democracy, ed. Tobias Hag-mann and Filip Reyntjens(London: Zed Books, 2016), 50-51.

31 Ibid, 51.

32 Ibid, 61.

33 Haben Fecadu, " OP-ED: Ethiopia must end the cul-ture of impunity to heal from decades of human rights violations. " (June 02, 2020): https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/06/oped-ethiopia-must-end-culture-of-impunity-to-heal-from-decades-of-human-rights-violations/

34 Emanuele Fantini, Luca Puddu. " Ethiopia And International Aid: Development Between High Modernism and Exceptional Measures ". Aid and Authoritarianism in Africa: Development Without Democracy, ed. Tobias Hagmann and Filip Reyntjens(London: Zed Books, 2016), 91.

35 Emanuele Fantini, Luca Puddu, Op cit, 92.

36 Ibid, 91.

37 Simone Gavazzi, " Democracy in Uganda. " Final Pa-per:https://www.academia.edu/40725915/Democracy_in_Uganda, 9/7/2020, at 14:52.

38 David M. Anderson, Jonathan Fisher." authoritarian-ism and the securitization of development in Uganda. " Aid and Authoritarianism in Africa: Development Without Democracy, ed. Tobias Hagmann and Filip Reyntjens(London: Zed Books, 2016), 61.

38 Ibid. 68.

40 Ibid. 68.

41 Jephias Matunhu," A critique of modernization and dependency theories in Africa: Critical assessment." African Journal of History and Culture, Vol: 3 (5), (June 2011), https://www.academia.edu/11724003/A_critique_of_moderniza-tion_and_dependency_theories_in_Africa_Critical_assessment, 68.

42 Luke Amadi, " Africa: Beyond the "new" dependency: A political economy. " African Journal of Political Science and International Relations, Vol: 6(8), (December 2012), 192, https://doi.org/10.5897/AJPSIR12.022.

43 Jack Jackson, Nkwocha Ifeoma Better, Boroh Stan-ley Ebitari. " Dependency and Third World Underde-velopment: Examining Production-Consumption Disarticulation In Nigeria." African Research Review, Vol: 10, N°: 4, (September 2016), 208-210, https://doi: 10.4314/afrrev.v10i4.15.

44 Negussie Siyum, " Why Africa Remains Underdevel-oped Despite Its Potential? Which Theory Can Help Africa Develop? ". Open Access Biostat Bioinform, Volume: 1, Issue: 2, (February 2018), https://crimsonpublishers.com/oabb/pdf/OABB.000506.pdf, 2-3.

45 Augustine A.O, " The Crisis of Underdevelopment in Sub-Saharan Africa: Multi-dimensional Perspectives." Journal of Political Sciences & Public Affairs, Volume: 6, Issue: 4, (October 18, 2018), 08, https://doi: 10.4172/2332-0761.1000338.

Bibliography:

1. Abrahamsen, R. (2005, January 01). Blair's Africa: The Politics of Securitization and Fear. Alternatives, 30(01). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/030437540503000103

2. Abrahamsen, R. (2016). Discourses of democracy, practices of autocracy: shifting meanings of democracy in the aid–authoritarianism nexus. In F. R. Tobias Hagmann, Aid and Authoritarianism in Africa: Development Without Democracy. London: Zed Books.

3. Amadi, L. (2012, December). Africa: Beyond the "new" dependency: A political economy. African Journal of Political Science and International Relations, pp. 191-203. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5897/AJPSIR12.022

5. A.O., A. (2018, October 18). The Crisis of Underdevelopment in Sub-Saharan Africa: Multidimensional Perspectives. Journal of Political Sciences & Public Affairs. doi:DOI: 10.4172/2332-0761.1000338

6. Armaments, Disarmament, And International Security. (2018). Yearbook. Stockholm: SIPRI. https://www.sipri.org/yearbook/2018

7. Buzan. B., O. W. (1998). Security: A New Framework for Analysis.London: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

8. Bernard, J. (2007, janvier). LesThéories de la Sécurité Environnementale : Regard Critique sur un Concept ambigu. Montréal, Université du Québec, canada.

9. Commission Européenne. (2017). Partenariat Clé de L’UE avec L’afrique. Bruxelles: Union européenne.

10. David M. Anderson, J. F. (2016). Authoritarianism and the securitization of development in Uganda. In F. R. Tobias Hagmann, Aid and Authoritarianism in Africa: Development Without Democracy. London: Zed Books.

12. EmanueleFantini, L. P. (2016). Ethiopia And International Aid: Development Between High Modernism and Exceptional Measures. In F. R. Tobias Hagmann, Aid and Authoritarianism in Africa: Development Without Democracy. London: Zed Books.

16. Jack Jackson, N. I. (2016, September). Dependency and Third World Underdevelopment: Examining Production-Consumption Disarticulation In Nigeria. African Research Review, pp. 205-223. doi:DOI: 10.4314/afrrev.v10i4.15

17. Jonathan Fisher, D. A. (2015, January). Authoritarianism and The Securitization of Development in Africa. International Affairs, pp. 131–151. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12190

18. Lars Buur, S. J. (2007). The Security-Development Nexus: Expressions of Sovereignty and Securitisation in Southern Africa. Stockholm: ElandersGotab AB.

19. Marriage, Z. (2016). Aid to Rwanda: unstoppable rock, immovable post. In F. R. Tobias Hagmann, Aid and Authoritarianism in Africa: Development Without Democracy. London: Zed Books.

20. Matunhu, J. (2011, June). A critique of modernization and dependency theories in Africa. . https://www.academia.edu/11724003/A_critique_of_modernization_and_dependency_theories_in_Africa_Critical_assessment

21. McDonald, M. (2008, December). Securitization and the Construction of Security. European Journal of International Relations, pp. 563-587. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066108097553

22. Meetings Coverage And Press Releases. (2020, February 20). Delegates Call for Critical Financial Support to Combat Terrorist Groups, as Sixth Committee Continues Debate on Eliminating Global Menace.

https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/gal3594.doc.htm23. Miles, W. F. (2012, DECEMBER). Deploying Development to Counter Terrorism: Post-9/11 Transformation of U.S. Foreign Aid to Africa. African Studies Review, 55(03), pp. 27-60.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/4390484725. Petřík, J. (2008). Securitization of Official Development Aid: Analysis of current debate. 2008 International Peace Research Conference (pp. 01-12). Leuven: Belgium Conflict Resolution and Peace-Building Commission.

27. Rossdale, C. (2009, June 11). The Constitutive Effects for Conflict and Insecurity of The Post-9/11 Discourse on Terrorism. E-International Relations, pp. 0111.

https://www.eir.info/pdf/150729. Tobias Hagmann, F. R. (2016). Aid and Authoritarianism in Sub-Saharan Africa After 1990. In F. R. Tobias Hagmann, Aid and Authoritarianism in Africa: Development Without Democracy. London: Zed Books.

31. Ugwuja, A. A. (2018, July). The United States Africa Command (Africom) And Africa's Security in The Twenty-first Century. University Journal of Management and Social Sciences (RUJMASS), 04(01), pp. 61-84.

33. WuyiOmitoogun, E. H. (2006). Budgeting for the Military Sector in Africa: The Processes and Mechanisms of Control. Stockholm: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.