Author: Eleni Kapsokoli, PhD, University of Piraeus, Piraeus, Greece

DOI: https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.22.3.5

Review paper

Received: October 9, 2021

Accepted: December 1, 2021

Abstract: During the last two decades, the growing threat of Islamic terrorism has raised numerous security challenges for both states and non-state actors. Cyberspace is weaponized by actors who conduct malicious activities, in order to achieve their goals. Terrorist organizations reflect the darker side of cyberspace. Terrorists use cyberspace to collect data, raise funds, conduct propaganda, spread radical ideologies and hate speech as well as for the purposes of radicalization, recruitment and operational planning. Social media platforms provide a fertile ground to extend the radical ideologies, to spread terror and to connect with people who share the same views. ISIS is considered a pioneer in utilizing the benefits that cyberspace offers. The Western Balkans is a region where ISIS is recruiting foreign fighters and lone-wolves. The European Union is the driving force for the activation of Western Balkans in countering cyberterrorism and developing relevant strategies.

Keywords: Islamic terrorism, cyberterrorism, media jihad, Western Balkan, Kosovo, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovin,

INTRODUCTION

The rapid development of the use of the Internet and the emerging information society, have led to the study of potential risks in a society. According to the latest statistics, there are 5.107 billions of cyberspace users that exchange an enormous amount of data on a daily basis (Internet Live Stats, 2021). It also found that users of cyberspace are "active" for at least 6.5 hours per day, Facebook users are 2.85 billion and 3.96 billion use social media platforms (Bryant, 2001). Cyberspace is a field of socio-political and military confrontation, in which terrorism is also active. There is a darker side to cyberspace, which is constantly challenging individual and collective security. From the above arises the question to what extent and how the development of information and communication technologies (ICTs) has affected the phenomenon of terrorism.

According to existing sources after 9/11, terrorism is constantly evolving in terms of its characteristics and means of action, but not in terms of its goals. The symbiotic relationship between terrorism and cyberspace is dominant and well-established (Hoffman, 2006, p. 56). According to Marshal McLuhan, without communication, terrorism does not exist (Torres Soriano, 2008, p. 2). The goal of both sides is to attract a larger audience for a long time. For terrorists, the biggest failure is to be ignored by their target audience (Dowling, 1986, p. 1). Terrorists exploit the benefits of cyberspace, they learn from the mistakes of the past and adapt to the needs and conditions of the present and the future (Kapsokoli, 2019, p. 677).

The EU’s perception on cybersecurity is rather broad and comprises all the cyber related threats (e.g. cybercrime, cyberespionage, hacking, cyberattacks and online terrorist activities). The Western Balkans’ national counter terrorism and counter violence and extremism strategies are influenced by the EU approach, which confirms the so-called “Brussels Effect”, meaning the embracing of European standards and regulations (Bradford, 2020). The Western Balkans states have adopted national strategies that address solely countering violence and extremism. They perceive terrorist activities like online radicalization, recruitment, funding and propaganda, under the prism of jihadism terrorism. Also, they do not include cyberattacks on information systems by terrorist organizations in their above strategies.

The purpose of the paper is to analyze how ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) uses cyberspace in the Western Balkans region and the counterterrorism strategies developed by these states. In order to achieve that, we will first analyze the use of cyberspace by terrorist organizations. In a latter phase, we will review the strategies that both the EU and the Western Balkan states (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, Serbia and North Macedonia) have developed in order to counter cyberterrorism, online radicalization and violent extremism. The end goal is to identify the shortcomings in the present strategies.

CYBERTERRORISM: CONCEPTUAL UNCLARITY

Cyberterrorism is a new wave of terrorism, with the same content but different way of expression. Terrorism seeks to gain attention through the publicity generated by its actions. The social media platforms facilitate the spreading of such messages (Collins, 1997, p. 1). Without publicity, terrorist actions won’t reach a broader audience and generate fear. Only by reproducing and transmitting terror and fear will terrorists be able to bring about the desired political change (Hoffman, 2006, p. 40). Cyberspace is the main means of transforming terrorism in modern times.

Cyberterrorism is becoming the latest catchphrase, however only a few people can grasp the true meaning of the term. Since the 2000s, both media and government reports have overstated the potential threat of cyberterrorism. The cyberterrorism hype has proven unwarranted, since no major disruption to national critical infrastructure (such as a “cyber 9/11”) has occurred.

There is no commonly accepted definition of cyberterrorism. The existence of numerous definitions in the literature highlights the need for adopting a clear conceptual framework on what consists an act of cyberterrorism. Cyberterrorism has entered the political jargon to describe a politically motivated attack on computers, networks and information systems or essential services (Oleksiewicz, 2017, p.p. 142-143). In 1997, Pollitt defined cyberterrorism as “a deliberate, politically motivated attack carried out by non-state groups or clandestine agents against information, computer systems, software and data with the result that people not participating in the fighting experience the violence” (Pollitt, 1998, p.p. 8–10).

There are narrow and broad definitions of cyberterrorism. The narrow definitions restrict the perception of what constitutes cyberterrorism, solely to cyberattacks (e.g. the use of ICTs to target critical infrastructure). A narrow definition was coined by Denning, defines cyberterrorism as “the convergence of cyberspace and terrorism. It refers to unlawful attacks and threats against computers, networks and the information stored therein. Further, to qualify as cyberterrorism, an attack should result in violence against persons or property, or at least cause enough harm to generate fear” (Denning, 2000).

On the other hand, broad definitions include a variety of malicious cyber activities which are labelled as cyberterrorism (e.g. online terrorist content). Gordon and Ford claim that a broader conception of cyberterrorism is needed in order to understand the true potential that cyberspace offers to terrorist activities (Gordon & Ford, 2002, p.p. 637, 642-643). They argue that by viewing cyberterrorism restrictively, as a means of targeting computers, the understanding of the phenomenon is too limited. Instead, they call for a broader understanding of the term, to include all terrorist actions (terrorism matrix) conducted through cyberspace and not just cyberattacks as such.

TERRORIZING VIA CYBERSPACE

Ayman al Zawahiri stated that “I tell you we are in a battle, and more than half of it is taking place in the battlefield of the media. We are in a media battle in a race for the hearts and minds of our Ummah” (Al Zawahiri, 2005).

Terrorism has tried to spread fear through cyberspace and social media in order to pose a threat to international security, peace and the stability of the international system. The main role of ICT’s in terrorism is crucial and has transformed the way terrorist operations are conducting. Spreading extremist beliefs around the world at a rapid pace is an important tool for radicalizing, recruiting and training terrorists.

Al Qaeda and ISIS are making extensive use of cyberspace and social media, turning terrorism into an even more complex and multi-layered phenomenon. They use increasingly decentralized electronic networks to learn and spread technical knowledge. These communities operate outside the physical control zones of groups, exploit emerging technologies, and develop new technological solutions when communications and their organizational structure are challenged. This cycle of innovation and adaptation poses a challenge in relation to counterterrorist operatios.

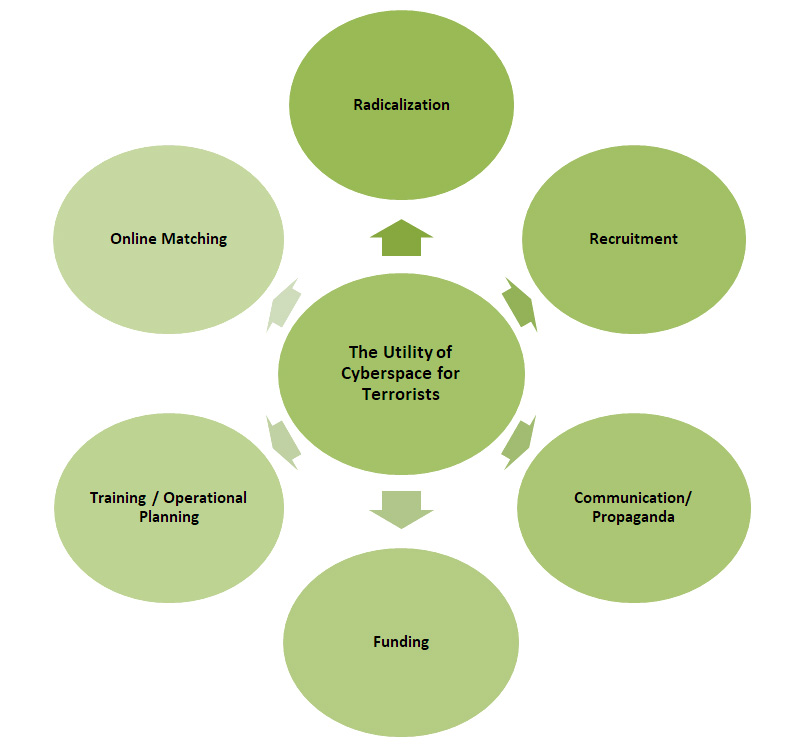

Terrorists are using cyberspace for purposes such as recruitment, radicalization, operational planning, training, propaganda, communication, free expression, funding and online matching (see figure 1).

The communication strategy of terrorists in cyberspace is facilitated by the above activities to achieve three main goals, the pursuit of attention, the recognition and gaining of respect and finally the legitimacy in certain target audiences (Nacos, 2010, p. 258). Depending on the type of terrorist organization, the above objectives differ. In general, terrorists seek to increase the impact of their messages on the recipient regardless of whether they achieve their short-term and long-term political goals.

Figure 1: The utility of cyberspace for terrorists

Terrorists are radicalized due to prior criminal record, mental health condition, family background and their social circle (Nesser, 2008). They feels like “scapegoats” or “victims” due to social inequality and injustice, pushing them to adopt radical and extreme positions. Quintan Wiktorowicz referred that Islamic radicalization includes a “cognitive opening” which is triggered by a crisis (personal, economic, social, political and religious). During this phase, the person is more vulnerable to radical ideas, values and beliefs, and readjusts these to its daily life (Wiktorowicz, 2005, p.p. 75-97).

Online matching, a trend introduced by ISIS, aims to identify women to serve as proper companions for ISIS fighters. Women travelling to the Caliphate (Syria and Iraq), were left with the impression that their life would be ideal. Nevertheless, they soon realized that they could not escape and were forced to stay, in order to ensure the survival of their families (Loveluck, 2020). ISIS promoted marriage and childbirth which contribute to the growth and expansion of the Caliphate. The women were responsible for the education of their children and the spreading of radical ideology to “produce” real and proper Muslims, fighters and future representatives of ISIS (Vale, 2019).

Cyberspace can facilitate the creation of groups of like-minded people who use it for the above activities (Fielder, 2013, p.p. 161-194). Therefore, in addition to being a potential target, a person can be used to influence, mobilize, intimidate another person or a whole population, its use has a social and psychological operational impact (Chapsos, 2010, p. 31). Radicalization will occur after the conversion and recruitment of an individual or a group of individuals, because their manipulation will be effective when they become the pawns for the execution of their actions. What they have created is a combination of propaganda and psychological warfare with the display of violence in public, as if it were a kind of marketing (Schmid, 2005, p.p. 127-136).

ISIS’S “ONLINE FOLLOWERS”

Western Balkans is multiracial, multiethnic and religiously divided inside their states. The religious’ division is between Orthodox Christianity, Catholicism, and Islam. The Islamic terrorism appeared in the Western Balkans during the early 1990’s when mujahedeen assisted the likeminded warriors during the Yugoslavia’s dissolution, which contributed to violent extremist and terrorism in the region (Bieber, 2003, p. 50). Former members of Islamic terrorist organizations, immigrated to Western Balkans and joined Muslim communities. As the result, the EU is facing the “home grown” jihadists who are Muslim immigrants or citizens that have been radicalized (Qehaja, 2016). In recent years, most jihadists are acting by themselves, as “lone-wolves”. Their actions are result of the processes of self-radicalization and self-training by using sources and material from the Internet.

Albania is a state with significant online terrorist content. Aleksandra Bogdani from BIRN highlights that “While the state grapples with returnee fighters and regulating mosques, experts say youngsters are still being radicalised online and warn of potential ‘lone wolf’ attacks”. Young Albanians are victims of online radicalization due to the limited religious knowledge and the extended use of social media networks which are the sources of ISIS propaganda (BIRN, 2016, p.p. 4-8). A serious example is Ebu Beklisa (Daci) who published a video on YouTube in June 2015 that threatened Albanians with terrorist activities in Albania and other Balkan states in case they do not embrace ISIS (Flamur Vesaj, 2015).

In North Macedonia, Fazli Sulja and Muhamed Shehu had published photographs to their social media profiles from their terrorist activities in the Syria (Stojkovski & Kalajdziovski, 2018, p. 36). The above terrorists felt like living an adventure and shared it with their followers to attract attention and respect. Another case, is the creation of a YouTube channel and Facebook page “Minber Media” by Rexhep Memishi with terrorist content which had million views and thousand followers (Stojkovski & Kalajdziovski, 2018, p.p. 19-20).

In September 2014, the Serbian authorities charged four ISIS terrorists for financing terrorist activities and recruiting fighters online (BIRN, 2016, p. 44). On July 2015, ISIS uploaded a video on YouTube in which, they issued threats against Serbia for future jihadist’s terrorist actions and the imposition of sharia law in the other countries of the Western Balkans. The video was published one day before prime-minister’s visit, Aleksandar Vučić to Srebrenica in order to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the slaughter of Bosnian Muslims during the war for the Yugoslav succession. In March 2016, a video was published in the social media in which armed men were burning the Serbian flag dressed in uniforms of the Bosnian Muslim army from the time of the wars in the 1990’s.

In 2016, ISIS published a video in which they requested the assassination of the mufti Zukorlić and identified him as a traitor who had brought disgrace to his position of imam for having been elected a member of parliament in a Christian state (Kyuchukov, 2018, p. 95).

In Montenegro, we have a phenomenon of “online preaching”, where Salafists-jihadists preachers (supporters of violent jihadism/takfirism) create an online class of believers in order to enhance their beliefs (Becirevic, 2018a, p. 3). Their preaching is more like a religious lecture and such examples of online jihadists’ preachers are Safer Kuduzovic and Elvedin Pezic (Becirevic, 2018a, p.p. 9-13). In May 2016, threats against three Muslim Montenegrins from Slakovic’s hometown Bar were published on his Facebook account, calling them “renegades who think they are Muslims”. In July 2016, a video was published with an armed man calling Muslims of Montenegro to join him in Syria or conduct terrorist actions against infidels in their regions (BIRN, 2016, p. 32-33).

Lavdrim Muhaxheri (Abu Abdullah al Kosovo) was self-declared as “commander of Albanians in Syria and Iraq” (American Foreign Policy Council, 2017, p. 573). He was a notorious ethnic-Kosovar ISIS leader, who first joined Jabhat al Nusra (affiliated with Al Qaeda). In 2013, a video showed Muhaxheri with two tanks as a background, requesting other Kosovars to join the jihad (Kraja, 2017, p. 24). He published a video in July 2014 with the beheading of a man who was accused of spying ISIS on behalf of Iraqi government (Moore, 2017). Another video is the Clanging of the Swords in 2014 released by Al Furqan Media. Muhaxheri appeared in this video with his Kosovo passport in one hand and a sword in the other hand, from the viewers to join jihad. In 2015, a video showed that he killed a man with a rocket (Conway & Brady, 2018, p.p. 76-77).

Ferizi (nickname Th3Dir3ctorY) was a member of a hacker group known as KHS (Kosova Hacker's Security), which aimed at Serbia's information infrastructure, but also delivered cyberattacks on international organizations (Alkhouri, Kassirer & Nixon, 2016, p. 5). Ferizi was convicted for unlawful access to a protected computer without permission for receiving information and providing material support to ISIS (information about 1,300 soldiers), for potential physical attacks (Department of Justice, 2016).

In a 20-minute video which was produced and published by AlHayat Media Center in the 2015, “Honor is in the jihad: a message to the people of the Balkans”, most of the “main characters” were Bosnian (Weiss, 2015). Salahuddin al-Bosni (Ines Midzic) and Abu Jihad al Bosni stated that “If you can, put explosives under the cars, in their houses, all over them. If you can, take poison and put it in their drink or food. Make them die, make them die of poisoning, kill them wherever you are. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, in Serbia, in Sandzak [a region in south-west Serbia]. You can do it” (Borger, 2015).

Despite the activities that promote their ideal lives in the self-proclaimed Caliphate, there is another aspect of religious discussions in the form of preaching and lecture. To be more specific, not all discussions have a violent and extremist content, because Salafists are not only jihadists, but also religious people with more “puritanical ideas”. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, most radical Bosnians use online platforms and free lectures delivered by jihadists preachers (Da’is) to attract more followers, who record videos to promote their ideology, posting lectures that are subject of discussion (Bećirević, Halilović & Azinović, 2017, p. 28). Videos with preaching are by Safet Kuduzovic who requested in July 2016, the deaths of Jews who curse the Prophet (Becirevic, 2018b, p.p. 18-19).

A REVIEW OF WESTERN BALKANS’S COUNTERING CYBERTERRORISM STRATEGIES

During the period 2012-2017 more than 1.000 terrorists travelled from Western Balkans to Iraq and Syria (Azinovic & Beciveric, 2017). The Western Balkans is one of the top cells of radicalized terrorists that become foreign fighters (Zakem, Rosenau & Johnson, 2017, p. 25). The recruiters manipulated the nationalist feelings of the citizens, the fragile regional peace and the internal conflicts, in order to develop a terrorist network (Azinovic, 2018, p. 15).

The national strategies of Western Balkans on counterterrorism are influenced by the EU. Currently, the Western Balkans states have adopted national strategies that address solely countering violence and extremism, and terrorism (conventional) and not cyberterrorism directly. Nevertheless, their national strategies address a wider matrix of terrorist activities, such as radicalization, recruitment, funding, propaganda and planning of terrorist actions, but their approach is under the prism of conventional terrorism. The trigger to develop strategies to combat violent extremism and online radicalization was ISIS (Von Behr, 2013).

ALBANIA

Albania adopted its first National Strategy on Counter Violence and Extremism in November 2015 and has four strategic objectives: 1) strengthen coordination at the local, national, and international levels, 2) encourage local research to improve the understanding of the conditions, factors and drivers of radicalization, 3) build community resilience and narrow the breeding ground for radicalization and violent extremism through tailored preventive community-based education and 4) reduce the impact of violent extremist propaganda and recruitment online by using social media to develop and disseminate alternative positive messages (promoting democratic values) (The Coordination Center for Countering Violent Extremism- Albania, 2015, 5).

Also, it had an Action Plan for its implementation in October 2017 (2017-2019) which mentions the following 1) focus on prevention and education of communities (families with rehabilitee foreign fighters), 2) support with social and economic means vulnerable groups, 3) provide psychological support to the terrorism victims and 4) strengthen community resilience with cultural and religious tolerance. All the above demands funding which is limited (Azinovic & Beciveric, 2017, p. 28).

The need of effective coordination and engagement of all stakeholders in this effort, was the creation of National CVE Coordinator in July 2016 and the Coordination Center for Countering Violent Extremism- Albania (CVE Center, 2017). Many fighters and their families who returned from Syria and Iraq, wanted to cut the ties with the terrorist organizations and become a part of society, but the process of rehabilitation is difficult due to the lack of proper programs of rehabilitation and de-radicalization in and out of prisons, the existence of stereotypes and the capacity and funding of these efforts (Azinovic & Beciveric, 2017, p. 29). But there are fighters who deceived the authorities and are still active. Albania developed a harmonized approach in many terrorist areas such as the push and pull factors of radicalization which can be more effective with programs of awareness, education, and employment and minimize the stereotypes.

NORTH MACEDONIA

North Macedonia adopted its National Strategy for CVE (2018-2022) in February 2018 which referred that “terrorist radicalization is a dynamic process whereby an individual comes to accept terrorist violence as a possible, perhaps even legitimate, course of action” (Government of the Republic of Macedonia, 2018, p. 10). Its goals are to refine and improve training and support for religious communities to counter online radicalization (Government of the Republic of Macedonia, 2018, p.p. 16-20). The Strategy was criticized by both the US and EU due to lack of references on online radicalization. The National Committee for Countering Violent Extremism and Countering Terrorism (NCCVECT) was established in August 2017 to oversee (non)-state (institutional) capacities and to enhance the cooperation between national and local authorities in the field of training and supporting for religious communities to counter online radicalization (Government of the Republic of Macedonia, 2018, p. 21).

The NCCVECT developed a strategy regarding the rehabilitation and reintegration of foreign fighters, of preventive measures with raising of awareness, strengthening of resilience against extremist and combat propaganda. Moreover, the NCCVECT created the local Community Action Teams (CATs) in September 2019 in order to strengthen the Local Institutional Capacity of the Community Action Team and Relevant Stakeholders, to strengthen the capacity of the local community and to create a platform for Youth Involvement (Strong Cities, 2019).

BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA

Bosnia and Herzegovina adopted a Strategy for Preventing and Combating Terrorism 2015-2020, which is an amended version of the previous security and counterterrorism strategies. This strategy does not specifically refer to online radicalization but only addresses that violent extremism and radicalization leads to terrorism and refers to new terrorist challenges (foreign fighters) but does not define them. The Strategy points out “special preventive measures to combat misuse of the Internet for terrorist purposes (widespread hate speech, hate crimes, discrimination, terrorist propaganda, radicalization, recruitment, financing, supporting and planning of terrorist activities)”. It also points out the possibility of prosecutions and imposition of sanctions for the potential terrorist activities.

The Strategy focuses on seven areas: legislation, institutional capacity and building, prevention, education- awareness, protection, investigation and response to terrorist activities. It has also issued an Action Plan for Implementation in October 2016 (2015) which includes measures of rehabilitation for the returned foreign fighters and the promotion of religious tolerance. These measures are not yet operationalized.

MONTENEGRO

Montenegro adopted the Strategy for Countering Violent Extremism 2016 – 2018 in December 2015 and an Action Plan for its implementation. The Strategy states that radicalization is achieved through the extremist propaganda with the use of ICT’s and social networks (Government of Montenegro, 2018, p. 2). It includes measures for de-radicalization and rehabilitation for foreign fighters and violent extremists (social programs and psychological support). The CVE strategy identified four key priority areas 1) understanding of drivers of radicalization in order to prevent them, 2) establishment of national-local partnerships and improvement of the capacities of the cybercrime unit, 3) implementation of joint activities as a response to drivers of radicalization and 4) implementation of monitoring and evaluation in order to eliminate future terrorist activities (Government of Montenegro, 2018, p. 5). Furthermore, Montenegro adopts a Cybersecurity Strategy 2018-2021 (2017), which refers to cyberterrorism and cybercrime (creation of terrorist organizations, attacks by individuals or groups, organized crime) (Government of Montenegro, 2017).

KOSOVO

Kosovo adopted a National Strategy on Prevention of Violent Extremism and Radicalization Leading to Terrorism 2015-2020 and an Action Plan for Implementation by 2020. The Strategy refers that the biggest threats appear to be ISIS and some Kosovo citizens that have been radicalized and joined this group. It points out four strategic objectives, 1) early identification of causes, factors and target groups, 2) prevention of violent extremism and radicalization, 3) intervention with the purpose of preventing the threat arising from violent radicalism and 4) de-radicalization and rehabilitation of radicalized persons. The Strategy refers that online radicalization is developed through the use of social media (YouTube, Skype, Facebook, Twitter, etc.), as well as that cyberspace facilitates ISIS in order to radicalize and recruit individuals. It addresses that the main problems of radicalization and terrorism are the unemployment and the social alienation, which facilitate the online recruiter to radicalize young people during an open forum or in a school (Government of Kosovo, 2015, p.p. 4, 14-16).

The four strategic objectives will be carried out with assistance of State agencies, institutions, civil society, religious communities, media companies and international organizations (Azinovic & Beciveric, 2017, p.p. 38-39). For the achievement of these goals, there is a need for better training and awareness to have a joint action in counter cyberterrorism and CVE activities. The main obstacles to achieve them are the insufficiency of the education system as well as the lack of funding and coordination. Quilliam Foundation and Kosovo government made an online campaign on Facebook and YouTube with the hashtag #NotAnotherBrother to combat the online propaganda of ISIS and to create a counter narrative (Kraja, 2017, p. 38).

SERBIA

Serbia adopted the National Strategy for the Prevention and Countering of Terrorism 2017-2021 and an Action Plan for Implementation in 2017. It pointed out the threat of radical Islamic movements and organizations that are responsible for radical behavior which leads to terrorist actions. It defined four strategic objectives 1) prevention of terrorism, violent extremism and radicalization, 2) protection by detection and elimination of terrorism threats and system weaknesses, 3) criminal prosecution of terrorists while respecting human rights, the rule of law and democracy and 4) system response in case of terrorist attack.

The first strategic objective presented five sub-objectives, the first one is the “Hi-tech communication systems and digital networks resilient to spreading of radicalization and violent extremism” which can affect a person indirect to commit a terrorist action and by using best practices and having a proper cooperation, the counter terrorist services could confront the spreading of terrorist propaganda and hate speech. The second important sub-objective is the “Skill of strategic communication” which highlights the use of Internet for recruitment and radical preaching which lead to terrorist actions. The Strategy referred to the potential threats of foreign fighters from Iraq and Syria and their terrorist activities (Government of Serbia, 2017, p.p. 3-6).

THE REGIONAL PERSPECTIVE

The EU in order to counter terrorist threats, adopted strategies and policies, established relevant institutions and agencies, and developed partnerships with third states and international organizations (Argomaniz, Bures & Kaunert 2015, p. 197). The EU tries to have a more active role in countering terrorism and reduce the radicalization and violent extremism in the Western Balkans region. The timeline of the EU’s attempts include the Action Oriented Paper on Improving Cooperation on Organised Crime, Corruption, Illegal immigration and Counterterrorism (2006) and the Council Conclusions on Cooperation with Western Balkan Countries on the fight against organized crime and terrorism (2008). In December 2015, the EU announced the Initiative on the Integrative and Complementary Approach to Counter Terrorism and Violent Extremism in the Western Balkans (Western Balkan Counterterrorism Initiative- WBCTi) (Kudlenko, 2019, p.p. 503-514; Council of the European Union, 2015).

The Strategy for the Western Balkans: EU sets out new flagship initiatives and support for the reform-driven region (European Commission, 2018b) compared to the previous ones, emphasizes more on counterterrorism and prevention and countering of violent extremism. The Joint Action Plan on Counter-Terrorism for the Western Balkans (European Commission, 2018a) focuses on the EU and Western Balkans cooperation on counterterrorism and countering of violent extremism. It includes five objectives:

1. A framework for countering terrorism and preventing/countering violent extremism,

2. Effective prevention and countering of violent extremism,

3. Effective information exchange and operational cooperation,

4. Build capacity to combat money laundering and terrorism financing and

5. Strengthen the protection of citizens and infrastructure.

The second objective highlights that they should address terrorist content online and reduce it through the creation of counter narratives and the support in capacity and training from EU Internet Referral Unit of Europol’s European Counter Terrorism Center. It mentioned the Western Balkan Counter-Terrorism Initiative (WBCTi) as part of the Integrative Internal Security Governance (IISG).

The IISG enables a coordinated, aligned and sustainable effort regarding internal security governance in the Western Balkans region. It is based on the following three pillars:

1. The WBCTi,

2. The WBCSCi (Western Balkans Counter Serious Crime Initiative) and

3. The WBBSi (Western Balkans Border Security Initiative) (IISG, 2021).

It is an EU-supported effort to respond to the developments related to terrorism, violent extremism and radicalization by maximizing the potential of regional cooperation. It identifies the legislative, institutional and operational needs, responses, analysis of gaps, synergies and approaches regarding internal security.

The WBCTi act at the Western Balkans region and member of this initiative is Turkey, Croatia and Moldova. It has the support of various important EU institutions such as European Commission, Council of the EU, the European External Action Service and the EU Counter Terrorism Coordinator. It aims to strengthen cooperation between the EU and the Western Balkans region. Its main goal is the support and development of counterterrorism and prevention and countering of violent extremism. It also points out the monitoring of Internet for terrorist content and the creation of counter-narrative social media campaigns (WBCTi, 2018).

CONCLUSIONS

After reviewing the relevant literature and national strategies on countering cyberterrorism and online violent extremism, we identified the following gaps. An important issue is the lack of conceptual clarity on key terms such as cyberterrorism, online radicalization, violent extremism and counterterrorism. A major obstacle to counter cyberterrorism is the fact that not all of the Western Balkans have developed the necessary strategies and that some of the existent strategies have not entered into force yet. Moreover, there are still activities on the dark web and other online platforms that are unknown to the counterterrorism authorities. Furthermore, there is no harmonization and standardization regarding the joint actions, legislation and approaches of all the actors involved. Additionally, the sharing of information and best practices is limited.

Adding to that, lack of resources (police personnel, prosecutors, technology and training) and lack of educational and awareness programs constrain the effectiveness of counter cyberterrorism efforts. The partial cooperation between private sector (IT and social media companies), public sector (civil society organizations, national institutions, and police) and citizens is a significant obstacle in achieving mutual trust, multileveled coordination and communication. It goes without saying, that there should be a balance between protection of human rights, internet freedoms, anonymity and privacy, and the enhancing of surveillance practices related to online terrorist content. Initiatives such as the implementations of the Radicalisation Awareness Networks in the Western Balkans project points to the right direction.

Citate:

APA 6th Edition

Kapsokoli, E. (2021). Cyber-jihad in the Western Balkans. National security and the future, 22 (3), 37-58. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.22.3.5

MLA 8th Edition

Kapsokoli, Eleni. "Cyber-jihad in the Western Balkans." National security and the future, vol. 22, br. 3, 2021, str. 37-58. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.22.3.5 Citirano DD.MM.YYYY.

Chicago 17th Edition

Kapsokoli, Eleni. "Cyber-jihad in the Western Balkans." National security and the future 22, br. 3 (2021): 37-58. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.22.3.5

Harvard

Kapsokoli, E. (2021). 'Cyber-jihad in the Western Balkans', National security and the future, 22(3), str. 37-58. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.22.3.5

Vancouver

Kapsokoli E. Cyber-jihad in the Western Balkans. National security and the future [Internet]. 2021 [pristupljeno DD.MM.YYYY.];22(3):37-58. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.22.3.5

IEEE

E. Kapsokoli, "Cyber-jihad in the Western Balkans", National security and the future, vol.22, br. 3, str. 37-58, 2021. [Online]. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.22.3.5

REFERENCES

1. Alkhouri, L., Kassirer, A. & Nixon, A. (2016). Hacking for ISIS: The emergent cyber threat landscape. Flashpoint.

2. Al Zawahiri, A. (9 July 2005). Letter to al Zawahiri to al Zarqawi. Federation of American Scientists. https://irp.fas.org/news/2005/10/letter_in_english.pdf

3. American Foreign Policy Council. (2017). The World Almanac of Islamism 2017. Rowman and Littlefield. Lanham.

4. Argomaniz, J., Bures, O. & Kaunert, C. (May 2015). A Decade of EU Counter-Terrorism and Intelligence: A Critical Assessment. Intelligence & National Security 30(2-3).

5. Azinovic, V. & Beciveric, E. (2017). A Waiting Game: Assessing and Responding to the Threat from Returning Foreign Fighters in the Western Balkans. Regional Cooperation Council. Sarajevo. https://www.rcc.int/pubs/54/a-waiting-game-assessing-and-responding-to-the-threat-from-returning-foreign-fighters-in-the-western-balkans

6. Azinovic, V. (2018). Regional Report: Understanding violent extremism in the Western Balkans. British Council-Extremism Research Forum.

7. Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN). (2016). Balkan Jihadists: the Radicalisation and Recruitment of Fighters in Syria and Iraq.

8. Becirevic, E. (2018a). Extremism Research Forum: Montenegro Report. British Council-Extremism Research Forum.

9. Becirevic, E. (2018b). Extremism Research Forum: Bosnia and Herzegovina Report. British Council-Extremism Research Forum.

10. Becirevic, E., Halilovic, M. & Azinovic, V. (March 2017). Radicalisation and violent extremism in the Western Balkans. British Council-Extremism Research Forum.

11. Bieber, F. (2003). The Serbian opposition and civil society: Roots of the delayed transition in Serbia. International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society, 17(1).

12. Borger, J. (25 June 2015). Isis targets vulnerable Bosnia for recruitment and attack. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jun/25/isis-targets-vulnerable-bosnia-for-recruitment-and-attack

13. Bradford, A. (2020). The Brussels Effect: How the European Union Rules the World. Oxford University Press.

14. Bryant, R. (2001). What kind of space is cyberspace?. Minerva- An Internet Journal of Philosophy.

15. Chapsos, Ι. (2010). Suicide Terrorism, modern martyrs or exploited prey at the altar of politics?. Journal of European Security and Defence Issues.

16. Collins B. (1997). The Future of Cyberterrorism. Crime and Justice International.

17. Conway, M. & Brady, S. (December 2018). A new virtual battlefield, How to prevent online radicalisation in the cyber security realm of the Western Balkans. Regional Cooperation Council.

18. Council of the European Union. (16 November 2015). Draft Council Conclusions on the Integrative and Complementary Approach to Counter-Terrorism and Violent Extremism in the Western Balkans. Brussels. https://www.eumonitor.eu/9353000/1/j9vvik7m1c3gyxp/vjz39avtvkxq

19. CVE Center. (2017). Council of Ministers Decision on the Creation of the Center of Coordination in Countering Violent Extremism. https://cve.gov.al/key-documents/?lang=en

20. Denning, D.E. (2000). Cyberterrorism: Testimony before the special oversight panel on terrorism committee on armed services US House of Representatives. Focus on Terrorism.

21. Department of Justice. (23 September 2016). ISIL-Linked Kosovo Hacker Sentenced to 20 Years in Prison. https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/isil-linked-kosovo-hacker-sentenced-20-years-prison

22. Dowling, R.E. (1986). Terrorism and the media: a rhetorical genre. Journal of Communication. Willey Online Library.

23. European Commission. (October 2018a). Joint Action Plan on Counter-Terrorism for the Western Balkans. https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/system/files/2018-10/20181005_joint-action-plan-counter-terrorism-western-balkans.pdf

24. European Commission. (February 2018b). Strategy for the Western Balkans: EU sets out new flagship initiatives and support for the reform-driven region. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_18_561

25. Fielder, JD. (2013). The Internet and dissent in authoritarian states. Conflict and Cooperation in Cyberspace. CRC Press. 1st Edition.

26. Flamur Vesaj. (30 December 2015). Albania charges Imam with recruiting for ISIS. Balkan Insight. BIRN. Tirana. https://balkaninsight.com/2015/12/30/jihad-ii-the-criminal-file-of-the-former-imam-sent-to-court-12-29-2015/

27. Gordon S. & Ford R. (November 2002). Cyberterrorism?. Computers & Security 21(7). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/222546033_Cyberterrorism

28. Government of Kosovo. (September 2015). Strategy on prevention of violent extremism and radicalization leading to terrorism 2015-2020. Pristina.

29. Government of Montenegro. (2017). Cyber Security Strategy of Montenegro 2018-2021.

30. Government of Montenegro. Ministry of Justice. (December 2018). Countering Violent Extremism Strategy 2016-2018. Podgorica.

31. Government of Serbia. (2017). National Strategy for the prevention and countering of terrorism for 2017-2021.

32. Government of the Republic of Macedonia. National Committee for Countering Violent Extremism and Countering Terrorism. (February 2018). National Strategy of the Republic of Macedonia for countering violent extremism (2018-2022). Skopje.

33. Hoffman, B. (2006). Inside Terrorism. 2nd Edition. Columbia University Press.

34. IISG. (2021). Integrative Internal Security Governance. https://wb-iisg.com/ last access 13/11/2021.

35. Internet Live Stats. https://www.internetlivestats.com/internet-users/ last access 13/11/2021.

36. Kapsokoli, E. (2019). The transformation of Islamic terrorism through cyberspace: the case of ISIS. Proceedings of the 18th European Conference on Cyber Warfare and Security in Coimbra, Portugal 4-5 July 2019. University of Coimbra.

37. Kraja, G. (September 2017). The Islamic State Narrative in Kosovo. Kosovar Center for Security Studies. Orishtine.

38. Kudlenko, A. (2019). The Western Balkan counter-terrorism initiative (WBCTi) and the capability of the EU as a counter-terrorism actor. Journal of Contemporary. European Studies, 27(4).

39. Kyuchukov, L. (2018). Balkan Islam: a barrier or a bridge for radicalization?. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. Sofia.

40. Loveluck, L. (28 June 2020). In Syrian camp for women and children who left ISIS caliphate, a struggle even to register names. Washington Post.

41. Moore, J. (8 June 2017). Who is Lavdrim Muhaxheri? ISIS Balkans Commander, Architect of Israel World Cup Plot, Now Dead. Newsweek.

42. Nacos, B.L. (2010). Terrorism and Counterterrorism. Penguin Academics.

43. Nesser, P. (2008). How did Europe’s Global Jihadis Obtain Training for the Militant Causes?. Norwegian Defence Research Establishment’s Terrorism Research Group. Norway.

44. Oleksiewicz, I. (July - September 2017). A Legal Assessment of management of the European Union Cyberterrorism Policy. Modern Management Review. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323124213_A_LEGAL_ASSESSEMENT_OF_MANAGEMENT_OF_THE_EUROPEAN_UNION_CYBERTERRORISM_POLICY

45. Pollitt, M.M. (February 1998). Cyberterrorism: Fact or Fancy?. Computer Fraud and Security(2).

46. Qehaja, F. (2016). Jihadists Hotbeds: understanding local radicalization processes. The Italian Institute for International Political Studies. Milano, Italy.

47. Schmid, A.P. (2005). Terrorism as psychological warfare. Democracy and Security, 1(2).

48. Stojkovski, F. & Kalajdziovski, N. (2018). Extremism Research Forum: Macedonia Report. British Council-Extremism Research Forum.

49. Strong Cities. (9 October 2019). SCN’s Local Prevention Network Model expands to the Western Balkans. https://strongcitiesnetwork.org/en/lpn-model-expands-to-the-western-balkans/

50. The Coordination Center for Countering Violent Extremism- Albania (18 November 2015). Albanian National Strategy Countering Violent Extremism. https://cve.gov.al/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/strategjia-2018-me-ndryshime.pdf

51. Torres Soriano, M.R. (2008). Terrorism and the mass media after al Qaeda: a change of course. Athena Intelligence Journal.

52. Vale, G. (October 2019). Women in Islamic State: From Caliphate to Camps. ICCT Policy Brief.

53. Von Behr, I., Reding, A, Edwards, C. & Gribbon, L. (2013). Radicalisation in the digital era: the use of the internet in 15 cases of terrorism and extremism. RAND. Brussels.

54. Weiss, C. (5 June 2015). Islamic State tours jihadists from the Balkans. https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2015/06/islamic-state-touts-jihadists-from-the-balkans.php

55. Western Balkan Counter-Terrorism Initiative (WBCTi). (26 June 2018). WBCTi - Integrative Plan of Action 2018-2020. https://www.rcc.int/swp/docs/180/wbcti--integrative-plan-of-action-2018-2020

56. Wiktorowicz, Q. (2005). A genealogy of radical Islam. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 28(2).

57. Zakem, V., Rosenau, B. & Johnson, D. (May 2017). Shining a Light on the Western Balkans Internal Vulnerabilities and Malign Influence from Russia, Terrorism, and Transnational Organized Crime. CAN Analysis & Solutions.