Authors: Francesca E. Strat, Saurav Narain

DOI: https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.26.1.1

Review paper

Received: November 3, 2024

Accepted: February 21, 2025

Abstract: The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) consists of ten states located close to the regional hegemon and at the center of the Indo-Pacific region. ASEAN has a balanced relationship with China, the dominant power, as it is the primary trading partner for most member states.

ASEAN and China have a strategic alliance until 2030 and have reaffirmed their relations with the union and the member states through joint military exercises for counterterrorism and maritime security, and agreements for sustainable agriculture cooperation. However, states like Philippines and Vietnam and western commentators such as the European Union (EEAS, 2024) have questioned China’s strategies in the region. They have alleged the employment of coercive practices such as the militarization of the South China Sea, disregard for international law, use of disinformation campaigns in ASEAN societies, and disruptions of supply chains. Therefore, this study aims to examine the relationship of ASEAN and its member states with China and, subsequently, analyze China’s exertion of influence within the association. This research focuses on the complex dynamics of how ASEAN member states manage their cooperative relationship with China in the face of significant challenges arising from territorial disputes in the South China Sea. Moreover, a section is dedicated to examining the influence of Western presence (US and Europe) in the region. This analysis will situate the issues faced by the China-ASEAN partnership in a wider perspective. Within the complex geopolitical landscape of Southeast Asia, the study aims to unravel the nuanced strategies employed by these nations to strike a delicate balance between fostering economic integration and addressing the geopolitical complexities arising from contested maritime territories. This paper utilizes public information, data from reliable sources, and expert interviews to substantiate its arguments.

Keywords: ASEAN, China, South China Sea dispute

Introduction

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), comprising ten Southeast Asian states, occupies a strategically significant position within the Indo-Pacific region. It functions as both a geopolitical and economic axis amidst competing great powers. The critical position of ASEAN in an evolving multipolar order is underscored by its centrality in transnational trade networks and its proximity to China, the dominant regional actor. ASEAN’s collective economic reliance on China - its foremost trading partner - has led to the formalization of the Strategic Partnership Vision 2030, incorporating various cooperative frameworks (Bi, 2021; Ling, 2021; Nguyen, 2019). Nevertheless, the strategic calculus of ASEAN is further complicated by the complex geopolitical tensions that persist between the two sides. Several ASEAN member states, as well as international observers, have expressed apprehensions about China’s assertive regional policies (Chap, 2023; Han, 2017; Kuik, 2015). These policies include the strategic dissemination of disinformation within ASEAN societies, the destabilizing interventions in regional supply chains, the disregard for international legal frameworks, and the militarisation of the contested South China Sea (Acharya, 2021).

The South China Sea (SCS) dispute has been the focal point of these issues, as it not only raises significant concerns of sovereignty but also has substantial implications for international maritime law and regional stability. Moreover, the involvement of Western powers, particularly the United States (US) and the European Union (EU), further complicates ASEAN’s strategic positioning. The geopolitical and economic interests of Western states are increasingly aligned with the support of a rules-based order in the Indo-Pacific (Press and Information team of the Delegation to ASEAN, 2022; U.S. Department of State, 2023). ASEAN states hold crucial political, economic, and strategic roles, warranting attention from both the US and China, as these hegemonic powers seek to enhance their alliances through various initiatives, such as the US Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF) or China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and “Shared Future for Mankind” (Chuvilov & Malevich, 2022; Koga, 2022a). Furthermore, prominent partnerships such as AUKUS, Quad, BRICS+, and the SCO significantly underscore the presence of this geopolitical competition in the region. As a result, Southeast Asian states occupy a unique yet beneficial position to influence the global order in the short to medium-term future. The decisions made by Southeast Asian states in the coming years will determine the course of the Sino-US power tussle on multiple domains.

Therefore, by taking the SCS dispute as the main arena of reference, this study aims at undertaking a critical examination of the evolving relationship between ASEAN and China, with an emphasis on the strategic responses of ASEAN member states to both cooperative and coercive aspects of Chinese influence. It also aims to evaluate the influence of Western engagement in the region, considering the extent to which ASEAN’s strategies are influenced by this broader geopolitical context. To systematically analyze these intricate dynamics, this study employs the PEST analysis, which examines Political, Economic, Social, and Technological factors that shape the decisions made by ASEAN member states. This research elucidates the nuanced mechanisms by which ASEAN endeavors to preserve regional stability and safeguard its autonomy within a polarized and complex Indo-Pacific landscape by utilizing public records, data from authoritative sources, and insights from expert interviews. Thus, this research aims to enhance scholarly comprehension of regional governance, strategic agency, and ASEAN’s geopolitical adaptability in the face of escalating regional tensions by contextualizing states’ responses within a broader theoretical framework.

Background Overview: ASEAN and the South China Sea Dispute

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations, founded in 1967 by five states (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand), currently consists of ten member states, which are strategically navigating their partnerships with various entities. Over the years, the organization morphed into a unique supranational entity established to foster political, economic, and strategic integration among its member nations, and it has since expanded to incorporate mandates of sustainability as well (ASEAN, 2024).

The association has historically maintained neutrality in the geopolitical arena, with numerous members involved in and establishing the Non-Aligned Movement during the Cold War (Lüthi, 2016). The adoption of the “non-interference principle” has significantly influenced ASEAN’s management of regional matters, as state autonomy and internal stability have typically been prioritized over the effective governance of the Southeast Asian region as a whole (Koga, 2018; Ruland, 2011). The decision-making process seems to have been significantly shaped by a prevalent apprehension of external involvement in internal affairs (Katanyuu, 2006). Thus, throughout the years, ASEAN’s political procedures have demonstrated a steadfast reluctance to intervene in the internal affairs of member states, compared, for example, to the more integrated European Union (Molthof, 2012). Despite the reinforcement of their commitment to each other through different initiatives to facilitate operations, such as a Free Trade Agreement and the establishment of the ASEAN Economic Community, ASEAN member states exhibit more accentuated differences regarding political and economic interests than EU member states. For instance, states such as Laos and Cambodia have different priorities and geopolitical allies as compared to the Philippines and Vietnam (see Beeson, 2016; Bradford, 2021; De Castro, 2022).

The distinction in priorities is also evident in the regularly revised mandates of ASEAN, with the yearly turnover of presidencies. The previous two agendas exemplify this dynamic adequately. In 2023, Indonesia adopted a more outward-looking agenda under the theme “epicentrum of growth” (ASEAN Indonesia 2023, 2023; Tey, 2023). In 2024, Laos’s theme is "ASEAN Enhancing Connectivity and Resilience", reflecting a more regionally focused strategy (ASEAN LAO PDR 2024, 2024; Gu, 2024). Indonesia’s chairmanship last year positioned ASEAN as a focal point of global economic growth, acknowledging external issues such as great power competition, the South China Sea dispute, and global warming as pivotal to preserving ASEAN’s centrality and neutrality. The Lao theme, while similarly aimed at fostering ASEAN cohesion, has embraced a more inward-looking approach in its agenda. According to Son (2023), this might be attributed to Laos’s minimal involvement in the South China Sea issue, relationships with Vietnam and China, or an absence of an Indo-Pacific strategy, which restricts its capacity to address both ASEAN objectives and its own interests. Both states have selected their respective visions for the future of ASEAN.

Despite diverging agendas, the most relevant and prominent faultline for ASEAN member states has always been the dispute in the South China Sea. The primary confrontations involve the Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam, and Brunei from ASEAN, with China as the principal adversary, the United States as a secondary challenger, and Taiwan as an additional opponent within the ASEAN region (Ahmad et al., 2021). In the past two years, multiple conflicts have occurred in the South China Sea between China and certain ASEAN member states, especially Vietnam and the Philippines. The new Chinese Coast Guard regulations allowing the Chinese coast guard to detain ships in its ‘domestic’ waters (the whole South China Sea) has raised concerns in the region (Johnson, 2024). Most recently, tensions between China and the Philippines over the Second Thomas Shoal in the South China Sea escalated to multiple skirmishes, particularly during a critical incident on June 17 (Misalucha-Willoughby, 2024). The conflict centered around Chinese vessels blocking Philippine resupply missions to the BRP Sierra Madre, a grounded warship the Philippines maintains on the shoal as a claim to sovereignty. Chinese forces deployed small boats to intercept Filipino vessels, causing damage and injuring Philippine personnel to prevent supplies from reaching the BRP Sierra Madre (Lariosa, 2024).

This escalation led to diplomatic responses from both nations, as well as condemnation from the United States and its allies, who emphasized the importance of freedom of navigation in the South China Sea (Lariosa, 2024). In response to these rising hostilities, China and the Philippines engaged in negotiations and reached a "provisional arrangement" by July. China has since allowed the Philippines to continue resupply missions without interference, although disagreements over the terms remained (Strangio 2024; Magramo 2024). Both sides continued to assert their sovereignty over the shoal, with the small strip of land one amongst many small islands in the sea highlighting the area's ongoing geopolitical significance (Darmawan, 2024). The western line of approach to promote freedom of navigation and respect for the rule of law is an attractive proposition for middle power states such as the Philippines and Vietnam. Therefore, western diplomatic and strategic support to some of these ASEAN states becomes an important counterweight within the maritime territorial dispute.

Thus, this paper takes the dispute as a frame of reference to evaluate the ASEAN-China relations. As evident in Figure 1, China's 9-dash line claim impedes sovereign maritime territories of at least half the ASEAN member states. Hence, the initial point of interference is how the South China Sea dispute impacts the relations between China and ASEAN states.

The importance of the contested sea can be attributed to three main things: they hold large resource deposits, resource rich fisheries, and astonishingly nearly a third of the world’s shipping trade passes through the territory (Macaraig & Fenton, 2021; Martin, 2024; Zhong & White, 2017). Additionally, the Spratly and Paracel islands are significant military and strategic outposts (Hensel, 2024; Tkachenko, 2016). The sea and its basin contain 3.5 billion barrels of petroleum and 40 trillion cubic feet of liquefied gas, just in the uncontested and explored parts (EIA, 2024a). The estimates for the contested and unexplored sea shelf are even higher. Furthermore, the region’s fossil fuel needs are increasing by nearly a percent every year with Asia-Pacific responsible for 37% of global petroleum consumption (EIA, 2024b). Possessing petroleum deposits therefore becomes a strong economic advantage for any state in the region, making the contested sea a key security hotspot to monitor. Therefore, it becomes imperative to analyze the impact of these simmering tensions on a broader scale of grand strategic options, such as politics, economics, society and technology.

Figure 1. China's Nine-Dash Line in the South China Sea (Britannica, 2024)

Research Question and Methodology

Thus, this research aims to answer the following question: “How do ASEAN member states balance China’s influence in the region amid South China Sea disputes?”

For doing so, the PEST analysis framework was implemented to dissect the ten ASEAN member states relations with China. Developed in business analytics, the PEST analysis uses four macro-environmental factors - Political, Economic, Social, and Technological - to identify opportunities and threats within the external environment that might affect strategic decision-making of a company, organization, or country (Bîrsan et al., 2016). Thus, this framework was adopted from and international security and diplomacy perspective to assess ASEAN member states’ trajectories of cooperation with China and the role the SCS dispute plays in transforming these relationships. The four factors of analysis were classified using Ho’s (2014; 6479) systematic PEST framework, which can be defined as follows:

- Political Factors (P): they cover various forms of government interventions and political lobbying activities in an economy;

- Economic Factors (E): they cover the macroeconomic conditions of the external environment but can include seasonal/weather considerations;

- Social Factors (S): they are social, cultural, and demographic factors of the external environment;

- Technological Factors (T): they include technology-related activities, technological infrastructures, technological incentives, and technological changes that affect the external environment.

Moreover, ontologically, PEST factors exist independently of any specific organization yet can exert direct or indirect influence on one another (Thompson and Martin, 2006; Ho, 2014).

For this study, a repository of academic, journalistic, and official state documents was compiled. Due consideration was given to a relatively similar number of western, Chinese, and Southeast Asian sources, survey data, commentaries, and academic texts up until October 15, 2024. Subsequently, the repository was put through a PEST analysis where every ASEAN member state was paired with each factor and studied separately. A matrix with the four macro environmental factors along the rows and the ten ASEAN member states in the columns was created. Utmost importance was given to the credibility of the sources and used high-indexed journal articles, discourse-leading media outlets, state narratives, along with economic figures, trade data, and military reports, to influence the analyses.

In the next sections, the result from the PEST analysis will be presented, followed by a conclusion to summarize the main arguments and address the limitations and avenues for further research.

Results and Discussions

Political Factors

The analysis of the Political factors in this PEST analysis comprised government statements, policies, diplomatic engagements, and participation in multilateral and unilateral organizations. The analysis examined the political engagements of each country to assess the political environment in the context of the South China Sea dispute and US-China rivalry. This analysis enabled discursive inferences regarding the grand strategy possibilities of a group of countries.

The impact of the South China Sea conflict is predominantly seen in the political landscape of the ASEAN region. The dispute profoundly impacts political decision-making and interactions with China among ASEAN member states, especially those asserting claims in the South China Sea (see Kipgen, 2018; Koga, 2022b; Meng, 2017). A number of claimant states have sought strategic, security, and diplomatic backing from the United States and, to some extent, Europe for their negotiations in the SCS (Hu, 2021). The West has openly recognised its capacity as a security actor and is positioning itself as the protector of a “rules-based order” in its discourse (Strating, 2019; U.S. Mission China, 2019). Consequently, the western political presence regarding maritime security, strategic diplomacy, and multilateral organizations has intensified in recent years.

Figure 2. Political leanings of the ASEAN member states.

This research identified three different blocs (Figure 2) in terms of their preference towards US/China competition from a political perspective.

a. The Pro-China Bloc: Laos, Myanmar and Cambodia

The three nations in this bloc are non-claimants in the South China Sea, hence exhibiting minimal resistance in their separate partnerships with China. Historically, Laos and Cambodia have been China's closest political partners, characterized by robust diplomatic and military interactions, a shared worldview, and strong ties among the three autocratic governments. The stability of the three regimes has facilitated the growth of their relations over time. The Lao and Cambodian regimes have rapidly integrated into the Chinese sphere of influence, collecting the benefits of Chinese investments in infrastructure, commerce, and military matters (Shambaugh, 2018). Cambodia and China’s political partnership has been strong since 2010, when they signed a comprehensive strategic partnership (ASEAN-China Centre, 2010). Ever since their diplomatic, military, and economic engagement has grown multifold on a year-by-year basis.

This strategic comprehensive has evolved during 2023, the year China and Cambodia celebrated the “Year of Friendship” marking the 65th anniversary of their diplomatic relations (Ho, 2023). They have since agreed to a “Diamond Hexgon” cooperation framework across the fields of politics, manufacturing, agriculture, energy, security, and cultural exchanges (Lim, 2023; Mifune, 2024; Strangio & Li, 2024). The Cambodian Prime Minister has symbolized the ‘diamond’ as the Cambodian people’s firm connection with the Chinese people (China MFA, 2023; Mifune, 2024). While officially it has adopted a stance of neutrality and non-alignment in the South China Sea dispute, it has often promoted China’s preferences in the issue. Within China-ASEAN forums, Cambodia has opted to support China’s position as opposed to the more ASEAN-focused demands of its partners. On the military side, the states have conducted a joint military exercise with over 2,000 personnel carrying out drills in land and sea (Liu, 2024).

As a result of this subservient partnership, Cambodia has given China access to the Ream Naval Base in the southwest part of the country. In December 2023, the first Chinese warships arrived at the port (Gan, 2023). Satellite imagery (see Figure 3) and journalistic reports have reported that the first Chinese warships have arrived at the port in December 2023, and the pier holds the capacity to hold much larger vessels (RFA, 2023; Head, 2024). While the Cambodian government has indicated that this is not a permanent base, its presence gives China a naval foothold in the Malacca Strait, the South China Sea, the Lembok Strait, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Within the international society, Cambodia has been among the first adopters of new Chinese frameworks such as the recent Global Security Initiative, the Global Development Initiative, and the Global Civilisation Initiative (Yao & Li, 2024).

On the other hand, while this Chinese affinity is growing, Cambodia has moved away from the western domain of influence. Following the Chinese Premier’s visit in 2016, Cambodia dramatically cut down its military exercises with the United States and has since nearly exclusively engaged with China (Luo, 2024). Since then, Cambodia has firmly been within China’s sphere of influence (Po & Primiano, 2020).

Figure 3. (Left) Ream Naval Base satellite images from Dec 2023 to oct 2024 (Head, 2024); (Right) Construction at the pier June 2022 and Oct 2024 - satellite images (Head, 2024)

Similarly, Laos has benefitted from its Chinese partnership as a result of Belt and Road investments. A similar party-system regime has allowed a cohesive cooperation between Laos and China over the last decade or so. In an interview to the Chinese state media, the Lao Prime Minister has called the Laos-China cooperation a “successful model” for other participating countries (Global Times, 2023). The two sides have reaffirmed their strategic partnerships with each other in July at the ASEAN foreign minister’s meeting and have shifted their focus on implementing a “Master Plan on the Creation of Laos-China, China-Laos Partnership" for 2024-2028 (Lao News Agency, 2024). As mentioned above, Laos’s 2024 presidency of the ASEAN has attracted significant diplomatic traffic towards the country this year with visits, summits, and meetings from leaders across the world in Vientiane. Laos’ theme of increasing connectivity and resilience has focused on its agenda to include actors from across the geopolitical spectrum (Bai & Weng, 2023; Gu, 2024).

Due to the skirmishes at the Second Thomas Shoal, the South China Sea conflict has taken center stage in discussions at ASEAN summits this year. While no material progress has been reported, Laos has maintained a combined China-ASEAN response, whereas other states such as Vietnam and the Philippines do not see benefit in that. In 2024, Laos has achieved significant progress as the ASEAN chair, as evidenced by the successful ASEAN-China FTA negotiations and the growing integration of regional economies (Koh, 2024). This has shifted the summit’s focus from the South China Sea to the benefits of regional economic integration, which is a net positive for China (Fong et al., 2024).

The situation in Myanmar is somewhat more intricate. China initially endorsed the military junta; however, as the junta's domestic control has been waning, and China has altered its approach. China’s involvement with Myanmar reflects its strategic interests and complex approach to regional security. While China maintains formal ties with Myanmar’s junta, recognising its control over key urban areas, it also engages with resistance groups along the border (Abb et al., 2024). This dual approach serves China’s security interests, particularly regarding border stability and the containment of illicit activities affecting its territory (Dean et al., 2024). By managing relationships on both sides of the conflict, China aims to secure its investments and influence in Myanmar while hedging against potential instability (Mosyakov et al., 2024).

In contrast, the United States’ relationship with Myanmar has been marked by tension since the military's suppression of pro-democracy movements in 1988 (Hiep, 2023). This tension further escalated after the violent crackdown on peaceful protests in 2007. The current conflict has only deepened U.S. condemnation as Washington supports democratic governance in the region and views the junta’s actions as a violation of human rights (Dafiryan, 2022). This divergence in approach from China highlights the broader competition between the U.S. and China as both seek to support governance structures aligning with their regional agendas.

b. Pro-United States Bloc: Philippines, Vietnam

The Philippines and Vietnam are the geographically closest ASEAN claimant states to China in the South China Sea. They are the two states that have experienced the most naval clashes with China. Consequently, both Vietnam and the Philippines have opposed collaboration with China, mostly because of these disagreements. In the last ten years, Beijing has menaced Vietnamese and Philippine outposts in the South China Sea and has ignored international tribunal decisions unfavourable to it. Although Vietnam and the Philippines openly seek to delineate their objectives in infrastructure and commercial alliances, the ongoing disputes and repeated confrontations further draw them towards the United States for military assistance (Wells-Dang, 2024).

Vietnam has chosen a model of “bamboo diplomacy”, a version of omnidirectional diplomacy (Do, 2022). During Xi Jinping’s first visit to Vietnam in six years, in December 2023, the two countries signed a comprehensive strategic partnership as a show of cooperation (Putra, 2024). Similarly, the US and Vietnam upgraded their comprehensive strategic partnership. Vietnam has presented itself as a promising option for the US in supply chain diversification in exchange for security and military support in the South China Sea (Shoji, 2024; Wells-Dang, 2024). On the other hand, the Philippines has been a closer United States ally due to a historical, long standing military partnership since 1951 Mutual Defence Treaty (MDT) (Lum, 2011). A strong US military position in the country is exhibited by the fact that Manila has offered Washington the use of nine of its military facilities (Tiwari, 2023). Through minilateral agreements, the Philippines is leveraging its US partnership to strengthen its partnerships with other US allies. July skirmishes in the South China Sea have further deepened the wedge between Chinese-Philippines relations (Ratcliff, 2024).

c. Cautiously Balanced States: Thailand, Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia, Singapore

The other five states - out of which three are claimants in the South China Sea - form the "cautiously balanced bloc". This term underlines the propensity of these states to balance their political preferences and aim to use different aspects of partnerships for different purposes. For Malaysia, Indonesia, and Brunei - three SCS claimant states - the biggest reluctance in the Chinese partnership is the territorial dispute. Nevertheless, for other aspects, a Chinese-focused worldview is politically successful compared to the United States. Historically, Brunei has been a steadfast ally of China; nonetheless, to protect its claims in the South China Sea, it has sought military assistance from the United States. (US Indo-Pacific Command, 2017).

Malaysia, as the first ASEAN country to forge official relations with China during the Cold War, holds a deep-rooted diplomatic foundation with Beijing. Under Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s administration, Malaysia is actively attracting foreign investment, particularly from Western and Asian companies looking to diversify supply chains away from China (Bing, 2024). This economic strategy aligns with Malaysia’s broader goal of balancing relations with both China and the West (Campbell 2024). However, Malaysia has taken a firm stance against China’s expansive territorial claims, particularly regarding the South China Sea. Malaysia is determined to safeguard its territorial integrity and enforce its sovereign rights within its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) (Zahari & Zulkifli, 2021). However, it also rejects interference by external powers in regional disputes. Malaysia’s approach to the South China Sea emphasizes regional dialogue, positioning itself as a proponent of diplomatic engagement over confrontation (Putra, 2024). Plans to construct a new naval base in Sarawak province on Borneo illustrate Malaysia’s commitment to bolstering its maritime security infrastructure (Azmi, 2024). This strategy allows Malaysia to maintain a ‘cautiously balanced’ stance politically.

As ASEAN’s previous chair, Indonesia has played a pivotal role in navigating regional security dynamics. Under its leadership, ASEAN maintained focus on unity and regional stability, while Indonesia took concrete steps to assert its sovereignty. In response to escalating intrusions by Chinese warships in the Natuna Islands, Indonesia has strategically boosted its military presence, improving both aerial and naval capabilities on Great Natuna Island to facilitate prolonged deployments (Maulana, 2022). Indonesia's strategy exemplifies its enduring dedication to an "independent foreign policy", maintaining equilibrium in its relations with both the United States and China (Priamarizki, 2022). It has declined U.S. requests for military access, favoring a "dynamic equilibrium" that seeks to prevent any single power from dominating the region (Laksmana, 2018). This balancing act underscores Indonesia’s concern for the stability of ASEAN amid intensifying U.S.-China competition and aligns with its vision for a multipolar Southeast Asia.

As a non-claimant state in the South China Sea, Thailand prioritizes ASEAN unity and stability, supporting regional dialogues over assertive actions. In recent years, Thailand has strengthened its defense ties with the United States, conducting joint military exercises and maintaining long standing security cooperation (Swaspitchayaskun & Surakitbovorn, 2023). At the same time, it has cultivated close economic and infrastructure partnerships with China, benefiting from Chinese investments under the Belt and Road Initiative (Sawasdipakdi, 2021). Reflecting its policy of neutrality, Thailand emphasizes a diplomatic stance that avoids direct alignment with either power, preferring a multipolar regional balance in Southeast Asia. This approach aligns with Thailand’s broader goals of preserving ASEAN cohesion and regional autonomy, supporting an environment where no single power dominates.

Beijing’s escalating diplomatic pressure on Bangkok can be attributed to its proximity to the Strait of Malacca and its transboundary rivers (Strangio, 2020). The adjacency of the Thai coast to this critical shipping route enhances its role in connecting Chinese ports to global markets, particularly in Europe and the Middle East. Additionally, the Mekong and Salween rivers, which flow through Thailand, are essential for the agricultural economy of its rural areas, further amplifying Thailand’s importance in regional resource management (Embke et al., 2024). These geographical factors put Thailand in a cautious position to secure its maritime routes, and by extension, stronger US support.

Economic Factors

This section of analysis looks at the economic factors of the PEST analysis. Trade and investment data, economic policies, sustainability partnerships, and multilateral and minilateral agreements have been used to perform an analysis of the economic environments the countries are operating in.

The overall economic trend in nearly every ASEAN member state is to grow their economic partnership with China. Despite their political differences in the South China Sea, the economic cohesion in the region has not been significantly affected. China, being one of the largest consumer markets globally, is an appealing trade partner for ASEAN member states, many of which have substantial areas of their economy in manufacturing and consumer goods (Figure 4).

Figure 4. (Top) Top ASEAN companies for Chinese FDI (MOFCOM, 2023) (Bottom) Top Chinese companies for ASEAN FDI (MOFCOM, 2023)

In 2020, ASEAN overtook the European Union as China’s largest trading partner (Flores, 2023). Despite the global economic slowdown in 2020, the ASEAN-China trade grew by 2.2%. Despite its maritime disputes, Vietnam is China’s largest trade partner in the region, which signifies the economic preferences in the region. Similarly, Brunei has had a strong economic dependence on China historically, and the effect of the SCS disputes is simmering in the member states' economic integration (Anwar, 2024).

The resilience that China and ASEAN economic partnership has exhibited in geopolitically tumultuous times shows the propensity of regional economic integration. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) signed in 2022, and the ASEAN China Free Trade Area has made it easier for the economies to navigate global tariffs and supply chain disruptions (Armstrong & Drysdale, 2022; Huong, 2022). RCEP currently covers fifteen countries, including all the ASEAN member states, China, New Zealand, Australia, Japan and South Korea. In the coming years, this agreement aims to eliminate up to 90% trade tariffs for its member states (HSBC, 2024).

This research finds that western sources in the dataset have solely focused on their own supply chain diversification efforts in ASEAN, but not the similar strategy applied by China (Hofstede, 2024; HSBC, 2024; Siew Leng 2024). Therefore, ASEAN has benefitted from increased investments in critical industries from both the West and China to its own benefit. The China-ASEAN partnership is well placed in terms of manufacturing of electric vehicles, semiconductor infrastructure, raw materials, consumer goods and equipment manufacturing, and Chinese companies intend to serve the ASEAN and the western markets through increasing operations in ASEAN. The Chinese government has made it clear that it will seek more economic agreements with ASEAN member states to increase the economic integration beyond the current levels (Oh and Hui Ting, 2023; Xinhua, 2023, 2024).

In terms of capital investment, Singapore has been the second largest source Foreign Direct Investment for China with 5.6% of total FDI in 2022 (MOFCOM, 2023). Since, the signing of RCEP trade between the two has increased 4.4% year on year reaching 71.9 USD in the beginning of 2023. Major Chinese companies like Alibaba and Tencent operate from Singapore and the country is often seen as a gateway for Southeast Asian and Western countries to access the Chinese markets. US trade and investment in Singapore matches Chinese statistics, signifying Singapore’s balancing of economic partnerships (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Singapore’s top export and import partners in 2022 (WTI, 2024)

Similar to their political posture, Laos and Cambodia rely heavily on their Chinese partnership as well. Both countries attract significant infrastructure investments from China through the BRI. In 2022, nearly 90% of all funded infrastructure projects in Cambodia were linked to China or Chinese companies (Mifune, 2024). As a result, nearly 40% of all of Cambodia’s debt is owed to China. The debt percentage for Laos to China stands at nearly half (Walker, 2024). Even though nominal trade for Laos and Cambodia with China has increased on a yearly basis, the Lao and Cambodian economies have not recovered from the COVID-19 economic slowdown, and the Chinese debt trap is detrimental to the recovery as well (Himmer & Rod, 2022; Martín Olea, 2024). Therefore, both of China’s closest political partners face the problem of over-dependence on the Chinese economy and debt-traps. Moreover, the increased public and military infrastructure investments project add to the dependency and the risk of loss of autonomy (World Bank, 2022).

Moving on, the economic relationship between Indonesia and China has grown significantly, with China being the second-largest source of foreign direct investment (FDI) in Indonesia, investing over 7 billion USD in 2022 alone (WTI, 2024). Much of this investment has gone into enhancing Indonesia's commodity processing, moving beyond raw exports to value-added products. Over the last decade, Chinese FDI in Indonesia has increased more than eightfold, reflecting a deepening economic integration focused on sectors like nickel processing, hydropower, and manufacturing (The Observatory of Economic Complexity, 2023). Bilateral trade between the two countries also reached around 149 billion USD in 2022, with China remaining Indonesia’s largest trading partner (Zhou, 2024; WTI, 2024).

Indonesia maintains a balance by also fostering trade and security ties with the United States, allowing it to pursue an “independent foreign policy.” While China has become Indonesia’s primary partner for exports and imports, Indonesia’s strategy of maintaining close ties with both powers is aimed at sustaining its autonomy. This balanced approach underscores Indonesia’s preference for promoting regional stability through its “dynamic equilibrium” approach (Poling, 2013).

Malaysia’s economic ties with China have deepened significantly as well, following similar cooperation trends as Indonesia. Chinese investment, especially under the BRI, has fuelled infrastructure projects across Malaysia, making China a vital contributor to the country's economic growth (Hutchinson & Yean, T. S., 2021). In 2023, Malaysia continued its efforts to attract Chinese investments, balancing its economic collaboration with a diplomatic approach. Despite this strong economic relationship, Malaysia also maintains important ties with the United States, especially in areas like security cooperation and defense (Kuik, 2023).

The Philippines is perhaps the country that attracts significant western trade and investment. For the Philippines, China has been a historical adversary; however, the post-Covid period has seen an interest to improve economic relations with China. In 2023, the two countries signed 14 Memorandum of Understandings and agreements with each other seeking to “shift relations to a higher gear” (China Briefing News, 2024). This included deals on agricultural and fisheries cooperation, digital and ICT collaboration, and a renewed memorandum of understanding (MoU) on the Philippines’ participation in China’s BRI. The two sides also formalized agreements on infrastructure investment, notably the handover of China-funded bridge projects in Manila and the signing of loan agreements for other critical infrastructure initiatives (Cruz & Juliano, 2021). While the Philippines maintains a strong western partnership in trade with Japan, US and South Korea, the country’s leaders have committed since the last two years to balance its trade with China (Mahmud 2024).

Thailand’s economic relationship with China is extensive, with China being its largest trading partner, especially in trade and infrastructure investment. Under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Thailand has seen considerable Chinese funding for projects such as the Thailand-China high-speed railway, which aims to enhance regional connectivity (Gill, 2023a). Chinese investments also extend to sectors like tourism, agriculture, and technology, further deepening their economic partnership. In comparison, Thailand’s trade relationship with the United States is smaller but remains strategically significant, as the U.S. is Thailand's third-largest trading partner and a key market for Thai exports, particularly electronics and agricultural goods (WTI, 2024; CRS, 2024). Despite China’s economic influence, Thailand values its partnership with the U.S., especially in defense and technology sectors, and seeks to maintain a balance between these two major powers in the region (Gill, 2023b).

Social Factors

This section includes the social, cultural, and demographic factors of the external environment to make an analysis of ASEAN member states’ social environment influencing the navigation of the geopolitical rivalry and the SCS dispute.

Citizens of numerous ASEAN member states exhibit a preference for Chinese cooperation, notwithstanding the maritime disputes among their countries. The analysis has found three main perspectives from the ASEAN societies (Figure 6). The three classifications are the following:

Figure 6. Social leanings of the ASEAN member states.

a. Pro-China Bloc (Indonesia, Malaysia, Laos, Cambodia, Brunei)

Half of the member states show an outright propensity to have China as a partner in the short to medium term future when compared to the United States. The pro-China orientation is relatively new for Malaysia and Indonesia, while Laos, Cambodia, and Brunei have maintained a pro-China position due to the alignment of their regimes with the regional hegemon. Cambodians hold the most favorable perception of China among the ASEAN member states, whereas Laos maintains a more balanced stance (Lin, 2023, Pang, 2017; Son, 2017; Watanabe and Samreth, 2024). Annual surveys have consistently demonstrated the favorable sentiment Cambodians had towards a collaboration with China. However, Laos has recognized its dependence on China, resulting in a decline in China's acceptance across several surveys. (ISEAS, 2023; 2024; Lin, 2023; Lowy Institute Asia Power Index, 2024). Nevertheless, China remains the most trusted partner for Laos.

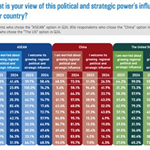

Moreover, another important factor is the great power’s response to global conflicts. Israel’s disproportionate response to October 7, 2023, attacks and the American legitimization of the response has caused an unfavorable opinion of the United States in ASEAN States. According to the ISEAS survey the people of ASEAN have voted the Israel-Hamas conflict as their top geopolitical concern ranking it above the South China Sea conflict (ISEAS, 2023; Ng, 2024). Political leaders across southeast Asia have invoked the support for the Palestinian cause in public. The Malaysian President draped a Keffiyeh in public in October 2023 and, along with Indonesia, was one of the harshest critics of Israel’s actions (Rachman, 2023). Nearly 43% of the ASEAN population is Muslim and Malaysia and Indonesia being the Muslim majority countries have shown the most solidarity to the Palestinian people, leading to a distrust towards the United States (Lin, 2024). Figure 7 shows the sharpest decline for the American support in nearly all ASEAN states except Singapore and Philippines.

Figure 7. Responses to the Question, “What is your view of this political and strategic power’s influence on your country?” in the ISEAS State of Southeast Asia Survey (2024)

b. Neutral (Thailand and Singapore)

Public opinion in Singapore and Thailand shows a cautious tilt toward maintaining strong ties with both powers. While in Singapore there is some affinity for China's rise, especially within Chinese-ethnic segments who view China as culturally resonant, however, there are also concerns about the dominance and assertiveness China displays regionally (Atlantic Council, 2022; Ja Ion, 2023). Singaporeans and Thais generally recognize the economic advantages of engaging with China but are cautious about excessive reliance (Walker, 2024; Lee, 2024). The U.S., on the other hand, is viewed favorably as a traditional security partner, although aspects of American politics such as in the middle east are sometimes perceived as unstable (Lim, 2023). A Lowy Institute survey reveals that Singaporeans predominantly endorse a balanced strategy, prioritizing economic engagements with China while maintaining defense relations with the United States (Ja Ion, 2023). The Singaporean government has underscored the need for a "value proposition", indicating the necessity to maintain relevance and strategic importance to both nations without excessive dependence (Ibid.). Some Thai people expressed apprehensions regarding the potential debt problems linked to Chinese investments and perceive U.S. investments as providing greater economic advantages, especially in manufacturing and job creation, suggesting a marginally more favorable perspective of the United States in comparison to China (Audjarint, 2023; Crispin 2022).

c. Pro-United States (Philippines, Myanmar, Vietnam)

Out of the three, Myanmar’s case is different. The Chinese backing of the military junta has eroded the support amongst the people in Myanmar. The United States, however, has been carefully navigating its support to popular resistance movements in the country gaining favorability amongst the people. The domestic conflict has occupied people’s mindshare over the conflict in the middle east or the war in Ukraine, therefore unlike the rest of the region there is more favorability to the United States (ISEAS, 2023).

Public opinion in Vietnam and the Philippines reflects a complex and often cautious view regarding the U.S.-China power competition. Both countries generally view the United States favorably, primarily due to security concerns in the South China Sea and long-standing partnerships. In Vietnam, sentiment toward China is marked by skepticism and historical mistrust, particularly given the tensions over maritime disputes. Data shows a consistent pattern of Vietnamese citizens holding more favorable views toward the United States than China, often due to concerns over China's assertive actions in the South China Sea (Liow and Connelly, 2017; ISEAS, 2022; 2023; 2024). Many in Vietnam support a balanced approach, with a significant portion of the public backing the government's strategy of strengthening ties with the U.S. and other partners as a counterbalance to China's influence.

In the Philippines, public sentiment is similarly mixed. While recent administrations have tried to improve relations with China to attract investment and support infrastructure projects, Filipino citizens tend to have a strong preference for U.S. relations, reinforced by defense treaties and joint security (Liow and Connelly, 2017). The Philippines has also expressed public skepticism about China’s intentions in the South China Sea. A significant number of Filipinos view the U.S. as a more reliable partner than China, especially in security matters, even though economic interdependence with China remains high (Fang and Li, 2022).

Technological Factors

This section comprises the analysis of the complex interplay in the technology sector between ASEAN member states, the US and China. The dataset analyzed in this section includes regional developments in the Information and Technology sector, innovation and research, technology manufacturing industries. The Sino-US geopolitical competition has intensified on the technological front as they scramble to emerge as the technological superpowers.

ASEAN nations are rapidly acknowledging the significance of information and communication technology (ICT) as a fundamental element of their economic diversification initiatives. Many ASEAN nations along with ASEAN as an organization itself have a record of working with China in digital infrastructure, Artificial Intelligence (AI), and smart cities (Sayavongs, 2023). However, the US being the leading innovator in advanced technologies, it is also an attractive partner to collaborate with in the technological sector. Both the US and China are engaging in making their semiconductors supply chains more resilient because of which the ASEAN member states are attracting Chinese and American companies to move parts of their supply chains in the region.

Brunei’s digital transformation is a key component of its economic diversification strategy, with an emphasis on building a “Smart Nation” (Khut, 2024). The government has introduced the Digital Economy Masterplan 2025 and the AITI Strategic Plan 2020-2025 to bolster digitalization. While Brunei collaborates with the U.S. for security applications, such as the acquisition of U.S.-made drones for surveillance and law enforcement, its technology strategy is focused on broad digital adoption and infrastructure building (United States Department of State, 2024). Cambodia’s technology ties with China are most significant, aligning with China's interests in Southeast Asia's digital transformation. This dual approach underlines Cambodia’s pragmatic balancing act in leveraging technology to drive economic modernization (Vannarith, 2024).

Myanmar’s military regime has deepened its technological cooperation with China, particularly for surveillance and internet control. China’s provision of advanced monitoring tools has enabled the junta to intensify censorship and identify dissenters, underscoring the role of technology in state security. This close relationship illustrates Myanmar’s dependence on China for digital and surveillance technology, reflecting its isolation from Western partners due to human rights concerns (Irrawaddy, 2024; Chao, 2024).

The Philippines grapples with significant cybersecurity challenges, exacerbated by its reliance on foreign technology. With Chinese technology investments under the "digital silk road" initiative, the Philippines has experienced both increased digital capacity and greater dependency on Chinese infrastructure (Brock, 2024). This reliance introduces security concerns, as dependency on foreign technologies can expose critical infrastructure to potential cyber vulnerabilities.

China’s “Digital Silk Road” initiative is a key avenue for its engagement with ASEAN-6, promoting the development of infrastructure such as 5G networks, AI, and e-commerce platforms (Harding, 2019). Huawei and ZTE are prominent players in this expansion, providing telecommunications infrastructure to nations like Malaysia and Indonesia, who benefit from affordable and rapid network development but face concerns over cybersecurity and data privacy (Herscovitch et al., 2022). In Malaysia, for instance, Chinese technology firms have played a substantial role in establishing its 5G infrastructure, despite U.S. warnings about potential security risks (Heydarian, 2021).

Conclusions

In conclusion, in recent years, China’s normative power within ASEAN has grown significantly, marking a notable shift in regional dynamics, even amid ongoing and often tense disputes in the South China Sea (SCS). This development highlights a complex and multifaceted interplay between ASEAN’s aspirations for regional cohesion, deep historical ties, and an evolving web of geopolitical considerations. China has deftly positioned itself as an essential partner for many ASEAN nations, leveraging economic, political, and cultural influence (Hong, 2019; Seth & Sean, 2021). However, a palpable cautiousness persists among most member states, many of whom remain wary of Beijing’s ambitions. Countries like Vietnam and Malaysia, for instance, have taken an outspoken stance against China’s expansive territorial claims, voicing their concerns on international platforms to maintain a delicate balance between economic engagement and the preservation of national sovereignty (Ahmad & Sani, 2017; Liang, 2018). These ongoing tensions serve as a microcosm of the broader dynamics at play in the South China Sea, where strategic imperatives frequently clash with economic dependencies, underscoring the dual imperatives of security and economic growth that ASEAN countries must navigate.

Nevertheless, even with China’s increasingly assertive stance, ASEAN members are acutely aware of the need to proceed with caution. Countries like Cambodia, which have cultivated deep diplomatic and economic ties with Beijing, find themselves navigating a precarious diplomatic balance. As one of the largest recipients of Chinese investment and military support in the region, Cambodia has aligned closely with China's initiatives on numerous occasions, often backing Beijing’s positions in ASEAN meetings and other regional forums. However, this alignment also underscores the broader challenge for ASEAN: finding a way to engage constructively with China while safeguarding regional autonomy and preventing excessive reliance on any one external power (Madu & Kusumo, 2024). The challenge lies in ensuring that economic partnerships with China do not compromise sovereignty or regional stability – an imperative echoed by leaders from other ASEAN countries like Indonesia and Singapore, who have called for balanced and principled engagement with external powers.

Meanwhile, as China’s influence grows, the United States has emerged as a vital counterbalancing security partner for several ASEAN countries. The U.S.-Philippines alliance, rooted in the 1951 Mutual Defense Treaty, remains a cornerstone of Washington’s security strategy in Southeast Asia (Cadelina, 2017). This alliance serves as both a security assurance for the Philippines and a means for the United States to maintain its strategic presence in the region, especially considering the increasing Chinese expansionism. Through this partnership, Washington aims to reassure its regional allies of its commitment to preserving stability and countering coercive actions in contested areas such as the South China Sea. However, the U.S. approach, which increasingly emphasizes mini-lateral alliances, sometimes challenges ASEAN’s centrality by inadvertently creating divisions within the bloc. While intended as a strategy to contain China's influence, these minilateral efforts have raised concerns within ASEAN about the potential erosion of regional unity and the risk of fostering alignment-based divisions that could undermine ASEAN’s cohesion.

Despite the multifaceted engagements between ASEAN, China, and the United States, ASEAN’s collective response to these evolving regional challenges remains constrained. The organization has often faced criticism for its perceived indecisiveness, particularly in addressing ongoing crises, such as the humanitarian and political crisis in Myanmar and its subdued response to the territorial disputes in the South China Sea. Although numerous diplomatic discussions and initiatives have been launched, they frequently lack the immediacy and enforcement power needed to address pressing regional threats effectively. ASEAN’s preference for consensus-based decision-making, while fostering inclusivity, can lead to delayed action on sensitive issues, limiting its efficacy as a regional security institution and prompting member states to seek alternative alliances for more immediate responses to security challenges.

Moreover, the limitations of the current research are significant and must be acknowledged. The study primarily relies on open-source data, which presents inherent constraints due to language barriers, selective information availability, and the use of secondary sources, which may lack the granularity needed for a fully comprehensive understanding of ASEAN-China relations. These methodological constraints inevitably impede the ability to gain an exhaustive perspective on the nuances and ongoing shifts within ASEAN-China relations and the broader implications for regional security and economic interdependence.

Literature:

1. “中华人民共和国外交部「中华人民共和国和柬埔寨王国关于构建新时代中柬命运共同体的联合声明(全文)” Joint Statement of the People’s Republic of China and the Kingdom of Cambodia on Building a China-Cambodia Community with a Shared Future in the New Era (Full Text)_Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. (2023). MFA China. https://www.mfa.gov.cn/web/gjhdq_676201/gj_676203/yz_676205/1206_676572/xgxw_676578/202302/t20230211_11023942.shtml

2. Abb, P., Zin Khay, S. K., Overland, I., & Vakulchuk, R. (2024). Road through a broken place: the BRI in post-coup Myanmar. The Pacific Review, 1-25.

3. Acharya, A. (2021). ASEAN and regional order: Revisiting security community in Southeast Asia. Routledge.

4. Ahmad, A. A., Salleh, M. A. B., & Ladiqi, S. (2021). China-ASEAN Disputes on South China Sea and the Implication of US Involvement. NEW ARCH-INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CONTEMPORARY ARCHITECTURE, 8(2), 235-247.

5. Ahmad, M. Z., & Sani, M. A. M. (2017). China's assertive posture in reinforcing its territorial and sovereignty claims in the South China Sea: an insight into Malaysia's stance. Japanese Journal of Political Science, 18(1), 67-105.

6. Anwar, A. (2024). Economic Relations Between China and ASEAN: The Shadow of the South China Sea Issue. Köz-gazdaság, 19(1), 23-37.

7. Armstrong, S., & Drysdale, P. (2022). The Implications of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) for Asian Regional Architecture. Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia.

8. ASEAN Indonesia 2023. (2023). ASEAN Indonesia. https://asean2023.id/en

9. ASEAN LAO PDR 2024 - ASEAN: Enhancing Connectivity and Resilience. (2024, October). ASEAN LAO PDR 2024. https://www.laoschairmanship2024.gov.la/

10. ASEAN Rises to Become China’s Top Trading Partner, Great Prospect for China + ASEAN Strategy. (2024). Retrieved November 3, 2024, from https://www.business.hsbc.com.cn/en-gb/campaigns/belt-and-road/asean-story-1

11. Audjarint, W. (2023, September 13). Experts: Thailand’s New Government Aims for Balance Amid US-China Rivalry. Voice of America. https://www.voanews.com/a/experts-thailand-s-new-government-aims-for-balance-amid-us-china-rivalry/7267324.html

12. Azmi, H. (2024). Malaysia eyes strengthened South China Sea defence with new naval base in Borneo | South China Morning Post. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/3281496/malaysia-eyes-strengthened-south-china-sea-defence-new-naval-base-borneo

13. Bai, H., & Weng, L. (2023). Ecological security pattern construction and zoning along the China-Laos Railway based on the potential-connectedness-resilience framework. Ecological Indicators, 146, 109773.

14. Beeson, M. (2016). Can ASEAN cope with China?. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 35(1), 5-28.

15. Bi, S. (2021). Cooperation between China and ASEAN under the building of ASEAN Economic Community. Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies, 10(1), 83-107.

16. Bing, N. C. (2024). Southeast Asians Are Using China Engagement to Compel Greater U.S. Regional Involvement. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2024/01/southeast-asians-are-using-china-engagement-to-compel-greater-us-regional-involvement?lang=en

17. Bîrsan, A., Shuleski, D., & Cristea, C. V. (2016). Practical Approach of the PEST Analysis from the Perspective of the Territorial Intelligence. Ovidius University Annals, Economic Sciences Series, XVI(2), 169–174.

18. Bradford, J. (2021). China's Security Force Posture in Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia. United States Institute of Peace.

19. Brock, J. (2024). ASEAN’s Cyber Initiatives: A Select List | Strategic Technologies Blog | CSIS. CSIS. https://www.csis.org/blogs/strategic-technologies-blog/aseans-cyber-initiatives-select-list

20. Brunei, U.S. Deepen Security Partnerships through Cooperation Afloat Readiness and Trainin. (2017). U.S. Indo-Pacific Command. https://www.pacom.mil/Media/News/News-Article-View/Article/1364237/brunei-us-deepen-security-partnerships-through-cooperation-afloat-readiness-and/https%3A%2F%2Fwww.pacom.mil%2FMedia%2FNews%2FNews-Article-View%2FArticle%2F1364237%2Fbrunei-us-deepen-security-partnerships-through-cooperation-afloat-readiness-and%2F

21. Cadelina, J. R. (2017). Strengthening Partnership: Enhancing Alliance with the Philippines to Counter China's Rise. Air Command and Staff College.

22. Campbell, C. (2024, September 19). What Does Malaysia’s Anwar Ibrahim Stand for? TIME. https://time.com/7022591/anwar-ibrahim-malaysia-prime-minister-interview-profile-balancing-act/

23. Chao, T. (2024). Myanmar regime uses Chinese tech to surveil internet users, report says—Nikkei Asia. Nikkei. https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Myanmar-Crisis/Myanmar-regime-uses-Chinese-tech-to-surveil-internet-users-report-says

24. Chap, C. (2023, September 12). ASEAN remains divided over China’s assertiveness in South China Sea. Voice of America. Available at: https://www.voanews.com/a/asean-remains-divided-over-china-s-assertiveness-in-south-china-sea/7264923.html (Accessed: 23/10/2024).

25. China (CHN) and Indonesia (IDN) Trade. (2023). The Observatory of Economic Complexity. https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-country/chn/partner/idn

26. China-Philippines: Bilateral Trade and Investment Prospects Prospects. (2024, September 20). China Briefing News. https://www.china-briefing.com/news/china-philippines-bilateral-trade-investment-and-future-prospects/

27. China, Cambodia agree to build comprehensive strategic partnership—ASEAN---China Center. (2010). ASEAN-China Centre. http://www.asean-china-center.org/english/2010-12/14/c_13648424.htm

28. Chongbo, W. (2024). China-Indonesia economic relations to strengthen in seven areas. ThinkChina - Big Reads, Opinion & Columns on China. https://www.thinkchina.sg/economy/china-indonesia-economic-relations-strengthen-seven-areas

29. Chuvilov, I. A., & Malevich, J. I. (2022). Community with a shared future for mankind, and how this concept is related to the Belt and road initiative. Journal of the Belarusian State University. International Relations, (1), 43-50.

30. COVID-19 Outbreaks and Headwinds Have Disrupted China’s Growth Normalization—World Bank Report. (2022). World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/06/08/covid-19-outbreaks-and-headwinds-have-disrupted-china-s-growth-normalization-world-bank-report

31. Crispin, S. W. (2022, June 9). China losing, US gaining crucial ground in Thailand. Asia Times. http://asiatimes.com/2022/06/china-losing-us-gaining-crucial-ground-in-thailand/

32. Cruz, J., & Juliano, H. (2021). Assessing Duterte's China Projects. Asia Pacific Pathways to Progress Foundation, Inc., March.

33. Dafiryan, M. (2022). ENSURING ACCOUNTABILITY FOR THE JUNTA CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY VIOLATION IN MYANMAR: USAGE OF THE ROME STATUTE AND POSSIBLE INVOLVEMENT OF THE UNSC VIA UNSCR REFERRAL. Padjadjaran Journal of International Law, 6(1), 1-19.

34. Darmawan, A. R. (2024, July). ASEAN Should be Prepared for a South China Sea Crisis. Australian Institute of International Affairs. https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/australianoutlook/asean-should-be-prepared-for-a-south-china-sea-crisis/

35. De Castro, R. C. (2022). The Philippines-US Alliance and 21st Century US Grand Strategy in the Indo-Pacific Region: from the Obama Administration to the Biden Administration. Defence Studies, 22(3), 414-432.

36. Dean, K., Sarma, J., & Rippa, A. (2024). Infrastructures and B/ordering: How Chinese projects are ordering China–Myanmar border spaces. Territory, Politics, Governance, 12(8), 1177-1198.

37. Do, T. T. (2022). Vietnam's emergence as a middle power in Asia: Unfolding the power–knowledge nexus. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 41(2), 279-302.

38. EIA. (2024). Regional Analysis Brief: South China Sea. The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). https://www.eia.gov/international/content/analysis/regions_of_interest/South_China_Sea/south_china_sea.pdf

39. EIA. (2024a, March 21). Regional Analysis Brief: South China Sea. International - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Available at: https://www.eia.gov/international/analysis/regions-of-interest/South_China_Sea (Accessed: 23/08/2024).

40. Embke, H. S., Lynch, A. J., & Beard, T. D. (2024). Supporting climate adaptation for rural Mekong River Basin communities in Thailand. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 29(7), 1-29.

41. EEAS (2024) South China Sea: Statement by the Spokesperson on recent developments | EEAS, EEAS. Available at: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/south-china-sea-statement-spokesperson-recent-developments_en (Accessed: 4 March 2025).

42. Fang, S., & Li, X. (2022). Southeast Asia under Great-Power Competition: Public Opinion About Hedging in the Philippines. Journal of East Asian Studies, 22(3), 481–501. https://doi.org/10.1017/jea.2022.35

43. Flores, W. L. (2023). China, ASEAN are natural partners. China Daily Global. https://regional.chinadaily.com.cn/en/2023-09/20/c_926787.htm

44. Fong, K., Martinus, M., Seah, S., & Lin, J. (2024, October 15). A Small Country’s Big Moment in ASEAN Amid Challenges. FULCRUM. https://fulcrum.sg/aseanfocus/a-small-countrys-big-moment-in-asean-amid-challenges/

45. Gan, N. (2023, December 6). The first Chinese warships have docked at a newly expanded Cambodian naval base. Should the US be worried?. CNN. Available at: https://edition.cnn.com/2023/12/07/asia/cambodia-ream-naval-base-chinese-warships-us-analysis/index.html (Accessed: 28/08/2024).

46. Gill, P. S. (2023a). Commentary: Thailand is at risk of becoming overly reliant on ‘big brother’ China. CNA. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/commentary/thailand-srettha-thavisin-china-ties-bri-railway-investment-us-concerns-3877126

47. Gill, P. S. (2023b). Thailand’s High-Speed Railway: On the Fast Track to Ties With China, But at What Cost? The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2023/11/thailands-high-speed-railway-on-the-fast-track-to-ties-with-china-but-at-what-cost/

48. Gu, J. (2024). Building partnerships for sustainable development: case study of Laos, the BRI, and the SDGs. Asian Review of Political Economy, 3(1), 1-25.

49. Han, D. G. X. (2017). China’s normative power in managing South China Sea disputes. The Chinese Journal of International Politics, 10(3), 269-297.

50. Harding, B. (2019). China’s Digital Silk Road and Southeast Asia. CSIS. https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-digital-silk-road-and-southeast-asia

51. Head, J. (2024). Does China now have a permanent military base in Cambodia? BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cx2k42n54kvo

52. Hensel, N. D. (2024). The Contemporary Strategic, Maritime, and Economic Significance of the South China Sea. In Security Dynamics in the South China Sea (pp. 65-97). Routledge.

53. Herscovitch, B., van der Kley, D., & Gatra, P. (2022). Localization and China’s Tech Success in Indonesia. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2022/07/localization-and-chinas-tech-success-in-indonesia?lang=en

54. Heydarian, R. J. (2021, July 9). SE Asia fragments on pro and anti-Huawei lines. Asia Times. http://asiatimes.com/2021/07/se-asia-fragments-on-pro-and-anti-huawei-lines/

55. Hiep, D. Q. (2023). The US Policy on Democracy in Burma (1988-2021). GLS KALP: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, 3(2), 1-13.

56. Himmer, M., & Rod, Z. (2022). Chinese debt trap diplomacy: reality or myth?. Journal of the Indian Ocean Region, 18(3), 250-272.

57. Ho, J. K.-K. (2014). Formulation of a Systemic PEST Analysis for Strategic Analysis. EUROPEAN ACADEMIC RESEARCH, 2(5). https://euacademic.org/ArticleDetail.aspx?id=831

58. Ho, R. (2023). China–Asean Relations: July 2023 to September 2023: Chronology of Events. China: An International Journal, 21(4), 212-216.

59. Hofstede, S. (2024, October 28). European Union searching for a safe shore: Catching supply chains moving to ASEAN. CEIAS. https://ceias.eu/european-union-searching-for-a-safe-shore-catching-supply-chains-moving-to-asean/

60. Hong, Z. (2019). China's Belt and Road Initiative and ASEAN. China: An International Journal, 17(2), 127-147.

61. Hu, B. (2021). Sino-US competition in the South China Sea: Power, rules and legitimacy. Journal of Chinese Political Science, 26(3), 485-504.

62. Huong, L. E. (2022). Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, ASEAN’s Agency, and the Role of ASEAN Members in Shaping the Regional Economic Order.

63. Hutchinson, F. E., & Yean, T. S. (2021). The BRI in Malaysia’s port sector: Drivers of Success and failure. Asian Affairs, 52(3), 688-721.

64. Institute, L. (2024). Map—Lowy Institute Asia Power Index. Lowy Institute Asia Power Index 2024. https://power.lowyinstitute.org/

65. Interesse, G. (2024, June 12). Singapore-China Bilateral Relations: Trade and Investment Outlook. ASEAN Business News. https://www.aseanbriefing.com/news/singapore-china-bilateral-relations-trade-and-investment-outlook/

66. International—U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). (2024). [US Energy Information Administration]. https://www.eia.gov/international/analysis/regions-of-interest/South_China_Sea

67. Irrawaddy, T. (2024, September 18). Myanmar Junta Taps China for Drone Tech After Losing Territory to Ethnic Armies. The Irrawaddy. https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/myanmar-china-watch/myanmar-junta-taps-china-for-drone-tech-after-losing-territory-to-ethnic-armies.html

68. Ja Ian, C. (2023). Amid Contending Narratives, A Read on U.S. and PRC Messaging in Singapore. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2023/11/amid-contending-narratives-a-read-on-us-and-prc-messaging-in-singapore?lang=en

69. Johnson, J. (2024, June 15). China Coast Guard’s new 60-day detention rules take effect. The Japan Times. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2024/06/15/asia-pacific/china-coast-guard-law-arrest/

70. Katanyuu, R. (2006). Beyond non-interference in ASEAN: the association’s role in Myanmar’s national reconciliation and democratization. Asian Survey, 46(6), .825-845.

71. Khut, V. (2024, June 24). Brunei: Challenges and opportunities in becoming a “Smart Nation.” The Scoop. https://thescoop.co/2024/06/24/brunei-challenges-and-opportunities-in-becoming-a-smart-nation/

72. Kipgen, N. (2018). ASEAN and China in the South China Sea disputes. Asian Affairs, 49(3), 433-448.

73. Koga, K. (2018). ASEAN’s evolving institutional strategy: Managing great power politics in South China Sea disputes. The Chinese Journal of International Politics, 11(1), 49-80.

74. Koga, K. (2022a). Getting ASEAN right in US Indo-Pacific strategy. The Washington Quarterly, 45(4), 157-177.

75. Koga, K. (2022b). Managing great power politics: ASEAN, institutional strategy, and the South China Sea. Springer Nature.

76. Koh, F. (2024, October 10). Upgrade to ASEAN-China Free Trade Agreement almost completed, important in time of growing protectionism: PM wong. CNA. Available at: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/asia/lawrence-wong-asean-summit-china-li-qiang-free-trade-business-green-digital-economy-gdp-4670121 (Accessed: 13/10/2024).

77. Kuik, C. C. (2015). Variations on a (Hedging) theme: Comparing ASEAN Core States’ alignment behavior. Joint US-Korea academic studies, 26, 11-26.

78. Kuik, C.-C. (2023). Active Neutrality: Malaysia in the Middle of U.S.-China Competition. United States Institute of Peace. https://www.usip.org/publications/2023/10/active-neutrality-malaysia-middle-us-china-competition

79. Kuok, L. (2024). The US-Philippines alliance and the 2024 US elections. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-us-philippines-alliance-and-the-2024-us-elections/

80. Laksmana, E. A. (2018). Drifting Towards Dynamic Equilibrium: Indonesia's South China Sea Policy Under Yudhoyono. SSRN.

81. Laos, China Strengthen Bilateral Cooperation. (n.d.). [Lao News Agency]. Retrieved November 2, 2024, from https://kpl.gov.la/detail.aspx?id=84595

82. Lariosa, A.-M. (2024, June 4). Philippine Marines Drew Firearms as China Seized Second Thomas Shoal Airdrop, Says Philippine Military Chief. USNI News. https://news.usni.org/2024/06/04/philippine-marines-drew-firearms-as-china-seized-second-thomas-shoal-airdrop-says-philippine-military-chief

83. Lee, T. (2024). A Small State Heavyweight? How Singapore Handles U.S.-China Rivalry. United States Institute of Peace. https://www.usip.org/publications/2024/04/small-state-heavyweight-how-singapore-handles-us-china-rivalry

84. Liang, C. (2018). The rise of China as a constructed narrative: Southeast Asia's response to Asia's power shift. The Pacific Review, 31(3), 279-297.

85. Lim, C. (2023). 2023/101 “Reviewing China’s Elite-Centric Approach in its Relations with Cambodia” by Chhay Lim.

86. Lim, J. Z. (2023, October 11). Tougher to articulate Singapore’s national interests amid US-China rivalry: New S R Nathan Fellow. The Straits Times. https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/more-challenging-for-singapore-leaders-to-articulate-foreign-policy-interests-amid-geopolitical-rivalry-expert

87. Lin, J. (2023a). 2023/55 “Changing Perceptions in Laos Toward China” by Joanne Lin. 2023(No. 55). https://www.iseas.edu.sg/posts/2023-55-changing-perceptions-in-laos-toward-china-by-joanne-lin/

88. Lin, J. (2023b, July 31). 9DASHLINE — The myth of the “vassal state”: China’s influence in Laos is waning. 9DASHLINE. https://www.9dashline.com/article/the-myth-of-the-vassal-state-chinas-influence-in-laos-is-waning

89. Lin, J. (2023c, December 21). Laos as ASEAN Chair: Flying into Headwinds. FULCRUM. https://fulcrum.sg/aseanfocus/laos-as-asean-chair-flying-into-headwinds/

90. Lin, J., Seah, S., Martinus, M., Suvannaphakdy, S., & Thao, P. T. P. (2023). THE STATE OF SOUTHEAST ASIA 2023. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/The-State-of-SEA-2023-Final-Digital-V4-09-Feb-2023.pdf

91. Ling, W. (2021). Creating strategic opportunities: the concept and practice of China-ASEAN security cooperation. Social Sciences in China, 42(3), 188-208.

92. Liow, J. C., & Connelly, A. L. (2017). Southeast Asian perspectives on US–China competition. Lowy Institute. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/southeast-asian-perspectives-us-china-competition-0

93. Liu, X. (2024, May 19). China, Cambodia proceed with joint land, naval exercise. Global Times. Available at: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202405/1312589.shtml (Accessed: 19/08/2024).

94. Lum, T. (2011). The Republic of the Philippines and US interests. Congressional Research Service.

95. Luo, J. J. (2024). Cambodia’s foreign policy (re) alignments amid great power geopolitical competition. The Pacific Review, 1-30.

96. Lüthi, L. M. (2016). The non-aligned movement and the cold war, 1961–1973. Journal of Cold War Studies, 18(4), 98-147.

97. Macaraig, C. E., & Fenton, A. J. (2021). Analyzing the causes and effects of the south china sea dispute. The Journal of Territorial and Maritime Studies, 8(2), 42-58.

98. Madu, L., & Kusumo, Y. W. (2024, September). The 2023 ASEAN Chairmanship and Indonesia's Foreign Policy: Implications for Regional Diplomacy in Southeast Asia. In 2nd International Conference on Advance Research in Social and Economic Science (ICARSE 2023) (pp. 663-674). Atlantis Press.

99. Magramo, K. (2024, July 24). Beijing and Manila made a deal in the South China Sea. But they’re already at odds over what was agreed. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2024/07/23/asia/south-china-sea-deal-explainer-intl-hnk/index.html

100. Mahmud, K. U. (2024, September 13). Sino-American Competition in the Philippines: Issues and Insights. Modern Diplomacy. https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2024/09/13/sino-american-competition-in-the-philippines-issues-and-insights/

101. Managing US-China Competition: The View from Singapore with Ambassador Bilahari Kausikan. (2022, August 17). Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/content-series/china-mena-podcast/managing-us-china-competition-the-view-from-singapore/

102. Martín Olea, C. D. (2024). Chinese influence in Southeast Asia under the Belt and Road Initiative: The cases of Cambodia and Thailand.

103. Martin, N. (2024, August 25). How south china sea tensions threaten Global Trade – DW – 08/25/2024. dw.com. Availabe at: https://www.dw.com/en/south-china-sea-tensions-pose-threat-to-international-trade/a-69926497 (Accessed: 30/08/2024).

104. Maulana, A. A. (2022). Gunboat Diplomacy in Natuna Waters from 2010-2020: Indonesia’s Deterrence in South China Sea Conflict. Insignia: Journal of International Relations, 9(1), 1-19.

105. McLaughlin, T. (2024, May 16). Southeast Asia Is in an Uproar Over Gaza. https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/southeast-asia-is-in-an-uproar-over-gaza/

106. Meng, L. Y. (2017). " Sea of Cooperation" or" Sea of Conflict"?: The South China Sea in the Context of China-ASEAN Maritime Cooperation. International Journal of China Studies, 8(3).

107. Mifune E. (2024, May 8). China–Cambodia “Diamond Hexagon” Cooperation Framework and Japan | The Japan Forum on International Relations. The Japan Forum on International Relations | 日本国際フォーラム英語サイト. https://www.jfir.or.jp/en/commentary/4399/

108. Mifune, E. (2024, May 9). China–Cambodia “Diamond hexagon” cooperation framework and Japan: The Japan Forum on International Relations. The Japan Forum on International Relations | 日本国際フォーラム英語サイト. Availale at: https://www.jfir.or.jp/en/commentary/4399/ (Accessed: 21/08/2024).

109. Misalucha-Willoughby, C. (2024, August). Navigating Turbulence at Second Thomas Shoal. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2024/08/navigating-turbulence-at-second-thomas-shoal?lang=en

110. MOFCOM. (2023). Statistical Bulletin Of FDI In China 2023. Ministry Of Commerce Of The People’s Republic Of China (MOFCOM). https://fdi.mofcom.gov.cn/resource/pdf/2024/03/14/564085296c88430c98e426696f3751e1.pdf

111. Molthof, M. (2012). ASEAN and the Principle of Non-Interference. E-International Relations, 1-7.

112. Mosyakov, D. V., Shpakovskaya, M. A., & Ponka, T. I. (2024). Myanmar’s Role in China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Vestnik RUDN. International Relations, 24(3), 439-449.

113. Ng, M. (2024). (NG-Hamas conflict top geopolitical concern in South-east Asia: ISEAS survey. https://asianews.network/israel-hamas-conflict-top-geopolitical-concern-in-south-east-asia-iseas-survey/

114. Nguyen, H. H. (2019). Economic Cooperation in ASEAN-China Strategic Partnership.

115. Oh, T., & Hui Ting. (2023, December 7). Enhancements to FTA among 24 deals signed to deepen Singapore, China cooperation. The Business Times. https://www.businesstimes.com.sg/international/global/enhancements-fta-among-24-deals-signed-deepen-singapore-china-cooperation

116. Opening doors in the ASEAN-China corridor. (2024, May 20). HSBC. https://www.business.hsbc.com.cn/en-gb/insights/accessing-capital/opening-doors-in-the-asean-china-corridor

117. Opinion | For Southeast Asians, worries about Israel-Gaza war trump even South China Sea. (2024, April 14). South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/opinion/article/3258844/southeast-asians-israel-gaza-war-more-worrying-even-south-china-sea-row-extremism-fears-grow

118. Pang, E. (2017). “Same-Same but Different”: Laos and Cambodia’s Political Embrace of China. ISEAS – YUSOF ISHAK INSTITUTE, 2017. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/ISEAS_Perspective_2017_66.pdf

119. Phuong, N. T. (2024). The South China Sea Disputes and the Evolution of the Vietnam-China Relationship | The National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR). https://www.nbr.org/publication/the-south-china-sea-disputes-and-the-evolution-of-the-vietnam-china-relationship/

120. Po, S., & Primiano, C. B. (2020). An “ironclad friend”: Explaining Cambodia’s bandwagoning policy towards China. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 39(3), 444-464.