DOI:

https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.26.2.1Review paper

Received: May 30, 2025

Accepted: July 12, 2025

Abstract: Terrorism and ideologically motivated violence constitute a persistent threat to global security, prompting extensive scholarly inquiry into the processes of radicalization and deradicalization.

This article employs a systematic and comparative analytical approach to elaborate on the key theoretical models of radicalization and deradicalization, with the aim of deepening the understanding of the psychological, social, and ideological factors that contribute to these phenomena. The methodological framework is grounded in a qualitative analysis of available academic and professional literature, incorporating comparative examinations of prominent theoretical models, as well as secondary analysis of reports and evaluations of existing programs. Through theoretical review, critical interpretation of current findings, and the development of conceptual models of radicalization and deradicalization, this study seeks to enhance comprehension of both the potential and limitations of contemporary approaches to these complex issues.

Keywords: radicalization, deradicalization, terrorism, extremism, extremist ideology.

Introduction

Terrorism and ideologically inspired violence represent enduring and serious threats to global security. Accordingly, over the past two decades, developed countries, the scientific and research community, and other relevant organizations have invested considerable efforts to gain a deeper understanding of terrorism and violent extremism. In order to develop effective measures for the prevention and countering of violent extremism, it is essential to comprehend the process of radicalization among potential adherents of extremist ideology.

Adopting a scientific approach, this article analyzes and systematizes the existing scholarly literature, employs comparative analysis to examine relevant theoretical models, and presents the main findings arising from the comparative evaluation of radicalization and deradicalization theories. In its applied dimension, the article further elucidates why the rhetoric of violent extremist groups appeals to certain individuals and how such groups disseminate propaganda and recruit new members.

The core assumption underpinning this study is that a comprehensive understanding of radicalization and deradicalization processes constitutes a crucial prerequisite for effectively addressing this form of security threat. Moreover, such understanding can contribute to the development of more effective intervention programs aimed at supporting radicalized individuals and facilitating their reintegration into society.

In pursuit of a clear and coherent presentation of the evidence and arguments that methodologically support the core assumption, the article is structured into an introduction, two main chapters that operationalize the core assumption, and a conclusion. Through a theoretical review of the most relevant models and the factors influencing an individual’s susceptibility to radicalization—as well as the methods employed for their comparison—this article draws and critically interprets a set of conclusions. Finally, it presents, compares, and explains the cognitive and emotional processes of radicalization, based on three key theoretical models.

The methodology employed for the comparative analysis of radicalization and deradicalization models involved a systematic review of existing theoretical frameworks presented in academic literature. Key models by leading scholars were selected based on their relevance, empirical grounding, and influence in the field of security studies. Each model was analyzed according to predefined criteria, including conceptual clarity, underlying assumptions, stages or phases described, and applicability to real-world interventions. The analysis focused on identifying commonalities and differences in how these models conceptualize the processes of radicalization and deradicalization, as well as their consideration of psychological, social, and ideological factors. This qualitative comparative approach enabled a nuanced understanding of the complex dynamics involved and informed the synthesis of complementary insights across models.

When discussing the radicalization of an individual, group, or collective, we are referring to a process composed of multiple phases, stages, or steps, culminating in the commission of a terrorist act. Numerous studies have been conducted across various scientific disciplines to address key questions such as: what drives individuals to commit acts of terrorism, what methods of radicalization are employed, and which individuals or social groups are more susceptible to radicalization. These studies share a common objective—to facilitate an in-depth understanding of the radicalization process and to apply the resulting insights effectively in efforts to counter radicalization.

The second chapter examines three prominent theoretical models of radicalization: Randy Borum’s conceptual model, Fathali M. Moghaddam’s psychological metaphor of the “staircase to terrorism,” and the analytical model developed by Mitchell Silber and Arvin Bhatt.

Deradicalization, in contrast, refers to a systematic effort aimed at deterring individuals from extremist beliefs and violent behavior. Successful deradicalization strategies do not rely solely on repressive measures but instead adopt a comprehensive approach grounded in an understanding of the psychological, social, and ideological factors that underlie the radicalization process. The third chapter analyzes the theoretical models developed by John Horgan and Daniel Koehler. Horgan’s model distinguishes between disengagement from violent behavior and ideological deradicalization, emphasizing the importance of providing practical support for individuals seeking to exit extremist groups, without necessarily requiring a complete ideological transformation. Koehler’s model, on the other hand, is based on a multidisciplinary, individualized, and institutionally supported approach, with a clear focus on cognitive transformation, psychological stabilization, and the social reintegration of radicalized individuals.

The article concludes with the main findings of the comparative analysis and emphasizes the importance of developing intervention programs aimed at support and reintegration, grounded in a comprehensive understanding of the aforementioned processes.

Radicalization – Definition, Causes, and Methods

The identification of the drivers and transformative phases of radicalization, as well as an understanding of how these elements can lead to political violence or terrorism, has been a central concern for scholars in the fields of security studies, warfare, and psychology. Between 2010 and 2018, the United States government invested over 20 million USD in research focused on radicalization as a contemporary phenomenon, with the goal of developing more effective measures for its prevention and suppression (U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2018).

Before further exploring this phenomenon, it is essential to define and clarify the key concepts used throughout this study, along with their possible synonyms. Extremism refers to fanatical beliefs or “extreme political or religious views” (Oxford University Press, 2017). According to the FBI, violent extremism encompasses the encouragement, incitement, justification, or support of violent acts aimed at achieving political, ideological, religious, social, or economic objectives. In contrast, terrorism is defined as the use of violence and intimidation—particularly against civilians—to achieve political aims.

A review of the relevant literature reveals that radicalization cannot be described as a fixed process with clearly defined characteristics. In other words, there is no single, uniform path that all individuals undergoing radicalization necessarily follow. Within the ideological spectrum, significant differences in background, demographics, and other contextual factors exist, making the radicalization processes experienced by individuals or groups inherently complex. These processes and their specific characteristics often stem from psychological and emotional factors unique to each individual (Jensen et al., 2016). Put simply, radicalization does not occur due to a single cause; rather, it is the result of a convergence of multiple interrelated factors that, when combined, can render an individual more vulnerable and susceptible to radicalization.

According to Jensen et al. (2016), the causes of radicalization are often the visible manifestations of underlying psychological and emotional processes. These processes are highly complex and frequently driven by feelings of inferiority, loss of meaning, and perceived societal injustice. As a result, individuals develop a strong need for some form of psychological or emotional compensation.

Furthermore, the same authors note that individuals often respond to extremist appeals in their pursuit of individual identity, or as a means of overcoming feelings of vulnerability or low self-esteem. This can also be explained by the widely acknowledged understanding that vulnerable individuals—such as adolescents undergoing puberty or individuals who have experienced trauma—frequently exhibit a pronounced need to belong to a group and to establish social bonds. Through this sense of belonging, they may derive their beliefs, values, or adopt a higher purpose promoted by the group (Jensen et al., 2016).

Weine and Ahmed (2012) emphasize that one of the factors that can increase an individual’s susceptibility to radicalization is social isolation (a perceived sense of marginalization) or the perception of discrimination by society (a sense of being subjected to unequal or unjust treatment). The same authors point out that individual trauma or crises—such as the loss of a family member or extremely poor living conditions—can also serve as catalysts pushing individuals toward extremism.

Zmigrod et al. (2019) add that individuals prone to excessive consumption of alcohol, drugs, or other intoxicating substances are more vulnerable to radicalization, and are more easily persuaded to commit acts of violence. In a similar vein, individuals suffering from psychological disorders (e.g., depression, suicidality, individuality disorders), particularly when combined with poor social status or poverty, may also face a significantly heightened risk of becoming radicalized (Gill et al., 2021).

When discussing methods of radicalization, a significant portion of recent literature identifies online radicalization as the most dominant form across all ideological groups (Jensen et al., 2018). This assertion is hardly surprising, given that the advent of modern communication technologies has exponentially expanded the reach of communication channels—both in terms of geographic scope and the breadth of their influence. It is also essential to emphasize the age structure of potential adherents to violent extremism. Broadly speaking, violent extremism is not inherently linked to any specific religion, nationality, civilization, or ethnic group. On the contrary, due to its global dimension, the phenomenon of radicalization that leads to violence represents a threat to the security and fundamental rights of citizens across all societies.

However, in the context of contemporary radicalization methods, this phenomenon must be understood within the framework of the increasingly blurred boundaries between online and offline life. Young people are particularly vulnerable to online radicalization, largely due to their deep engagement with digital communication technologies, as well as previously mentioned psychological, social, and economic factors.

Moreover, it is reasonable to argue that the dissemination of violent extremist ideology via the internet has shortened the overall duration of the radicalization process (National Institute for Justice, 2018). Consequently, the online radicalization of youth constitutes a particularly complex challenge—one that requires innovative, sustained, and globally coordinated responses, underpinned by strong commitment to collaboration among all relevant stakeholders at both national and international levels (Alhendavi, 2016).

Earlier studies consistently highlight the considerable efforts invested by extremist groups in recruiting new followers. For instance, Al-Qaeda reportedly organized seemingly informal gatherings at carefully selected locations, with pre-planned programs designed to attract potential recruits. In groups such as Al-Qaeda, radicalization most commonly occurs through a top-down process, meaning that the initiative for radicalization originates within the extremist organization and is strategically directed toward potential adherents (i.e., top-down radicalization).

However, more recent literature emphasizes the increasing prevalence of informal modes of disseminating extremist ideology—often through individual networks, such as friends or family members (Bakker, 2016). Of particular concern to security services is the phenomenon of self-radicalization, whereby individuals independently and autonomously radicalize through their social environments and online communication platforms, only subsequently initiating formal contact with extremist organizations on their own accord (Sageman, 2008). In such cases, the radicalization process follows a bottom-up trajectory.

Borum’s Conceptual Model of Radicalization

By observing and studying violent extremist groups with diverse ideologies, Randy Borum identified recurring factors among individuals and groups involved in the process of radicalization. Borum’s conceptual model of radicalization explains the process through which individuals gradually adopt extremist attitudes and behaviors, often to the point where they are willing to use violence in the name of a particular ideology (Borum, 2012).

According to Borum, the radicalization process unfolds through four distinct stages. The first stage, “It’s not fair,”pertains to an individual who experiences a sense of injustice within society, the community, or their individual life. The development of this sense of injustice is influenced by the individual's objective or subjective perception of reality. Factors contributing to feelings of dissatisfaction and injustice may include social and economic problems (e.g., unemployment, poverty), perceptions of social inequality or corruption, political events or decisions perceived as unjust, as well as individual experiences or traumas that intensify the sense of injustice. Regardless of whether the perception of injustice is objective or subjective, the individual or group modifies their belief system to hold that things are not as they should be (Borum, 2003:8).

The second stage, “It’s not right,” begins when the individual with a strong sense of injustice perceives that the injustice is directed specifically at themselves or the group to which they belong. This perception fuels further development of resentment and grievance.

In the third stage, “You are to blame,” the dissatisfied individual seeks to identify those responsible for their condition. Responsibility and the sense of injustice are assigned to a particular individual or group, which becomes the primary cause of their dissatisfaction and is deemed the “culprit” for the situation.

The fourth stage, “You are evil,” represents the final phase in which the identified individual or group is demonized. At this point, the already radicalized individual concludes that violence is a justified means to address the perceived injustice. Demonizing the target facilitates and legitimizes the use of force to defeat them. Additionally, this phase involves the polarization of the individual’s in-group from others (the so-called “us versus them”), where the in-group is viewed as good, and the others as evil. This perception fosters the moral justification of violent acts. Furthermore, Borum notes that while ideology may be a factor, it is not necessarily the primary motivator behind committing terrorist acts (Borum, 2003:9).

Beyond ideological understanding, it is also important to consider the behavioral perspective of individuals undergoing radicalization. To comprehend motives and to predict and ultimately prevent behaviors or activities of radicalized individuals, it is necessary to understand their worldview and perception of reality. This is a mental-behavioral phenomenon known in psychology as social cognition. Borum argues that ideology is often used by individuals predisposed to criminal and aggressive behavior to justify their actions. If one understands the “maps” held by their adversaries, it becomes easier to understand and predict their actions (Borum, 2003:8).

Borum’s conceptual model of radicalization can be illustrated through the empirical case study of the “Unabomber.” Specifically, Theodore Kaczynski was a brilliant mathematician and a former professor at the University of California, Berkeley. He was born in the United States to a family of Polish descent. During his primary and secondary education, Kaczynski advanced rapidly due to his exceptional intellect, skipping several grades. He would later describe this experience as traumatic, as it hindered his ability to integrate socially and made him a target of verbal abuse.

At the age of 16, Kaczynski enrolled at Harvard University, where he participated in controversial psychological experiments conducted by former military psychologist Henry A. Murray, who specialized in stress research. Kaczynski later claimed that these experiments had a profound impact on his emotional stability and contributed to the development of a deep-seated fear of mind control. He went on to obtain both his master’s and doctoral degrees in mathematics from the University of Michigan. He subsequently accepted a position as a mathematics assistant professor at Berkeley but resigned without explanation after three years. Despite his intellectual brilliance and the respect he garnered from colleagues, Kaczynski was known during this period as a “lone wolf.”

Following his resignation, he withdrew from society and began living in isolation in a remote cabin. Disillusioned with technological progress and modern civilization, he began constructing bombs and planning random acts of violence. His intended targets were individuals associated, in some way, with the advancement of modern technology. In 1978, he sent his first handmade explosive device to Northwestern University. Over the next 17 years, he continued to mail or personally deliver increasingly sophisticated bombs, which ultimately killed three individuals and injured over twenty others.

Table 1. Application of Borum’s Model to the Case of the “Unabomber”

Source: Authors

In 1979, the FBI launched an investigation under the code name “UNABOMB” to investigate these incidents. Despite extensive investigative and forensic efforts, the task force was unable to identify the perpetrator. A major breakthrough occurred in 1995 when Kaczynski submitted his manifesto to the FBI, which subsequently decided to publish it through the media. Theodore’s brother, David Kaczynski, recognized the writing style and thematic content of the manifesto as consistent with his brother’s and provided the FBI with personal letters and documents authored by him. On April 3, 1996, Theodore Kaczynski was arrested. A subsequent search of his cabin revealed a large quantity of bomb components, 40,000 pages of handwritten journals detailing bomb experiments and attack plans, as well as one fully constructed bomb ready for deployment. The collected material was of a great importance for the subsequent analysis of this individual’s radicalisation process.

Moghaddam’s Psychological Metaphorical Model

With the aim of understanding the process of radicalization, Fathali M. Moghaddam employed a metaphorical "staircase model" that leads from the ground floor to the top of a building where a terrorist act occurs. The staircase to terrorism model is conceptualized as consisting of a ground floor and five ascending floors, each characterized by a distinct psychological process. Whether an individual remains on a particular floor or ascends further depends on the doors and spaces they perceive as open to them. As Moghaddam explains, an individual climbing the stairs sees fewer and fewer choices, until the only possible outcome is the destruction of others, themselves, or both (Moghaddam, 2005).

The ground floor contains the largest number of individuals who perceive a sense of injustice. Although many people experience injustice and feel relatively deprived, only a portion ascend to the first floor in search of solutions. To understand those who climb to the top, it is essential to comprehend the level of perceived injustice as well as feelings of frustration and shame among those on the ground floor. Moghaddam highlights the central role of psychological factors for individuals on the ground floor. Psychological research underscores the fundamental importance of perceived deprivation, noting that perceived deprivation is a subjective experience (Collins, 1996). The perception of injustice may arise from various causes, including economic and political conditions, as well as threats to individual or collective identity (Taylor, 2003). Due to religion’s unique capacity to serve identity needs, in cases of religious fundamentalism, the most significant factor is the perceived threat to identity (Seul, 1999). Religious fundamentalists perceive the imposition of Western lifestyles and values as a threat, believing that these undermine their traditional ways of life. Other factors, such as poverty and lack of education, do not necessarily influence the psychological factor, as it is well-documented that radicalized individuals often come from affluent families and possess high levels of education. In conclusion, the perception of fairness is paramount for those on the ground floor. If individuals do not see opportunities for individual participation in resolving their problems and believe they lack influence in decision-making, they are more likely to continue ascending to the first floor. The behavior of those who reach the first floor is shaped by two psychological factors: the perception of opportunities for individual participation in improving their situation (Taylor & Moghaddam, 1994) and the perception of procedural justice (Tyler, 1994). The crucial question is whether there are doors that an individual motivated to advance in the social hierarchy can open, i.e., how the individual perceives their options for combating injustice. Participation in decision-making processes is a key factor in perceptions of justice and legitimacy of authority (Tyler, 1994). Moghaddam proposes contextualized democracy as a solution—a sociopolitical order that enables participation in decision-making and social mobility through the use of local, culturally appropriate symbols and strategies (Moghaddam, 2002; Moghaddam, 2004).

Upon reaching the second floor, individuals who previously felt injustice begin to develop feelings of anger and frustration. Several psychological theories suggest that at this stage, such individuals experience what is called displaced aggression, i.e., blaming "others" for their perceived problems. Moghaddam notes that feelings of anger and frustration at this level are often intensified by the influence of leaders who encourage them to direct their aggression towards the enemy. Leaders and organizations provide direct and indirect support for the physical expression of aggression, and individuals predisposed to physical aggression against the enemy continue to ascend the stairs. Those who climb to the third floor begin to develop a firm belief that violence is a justified response to perceived injustice, often under the influence of an ideology that legitimizes violence as a means to achieve higher goals. Individuals on the third floor start perceiving terrorism as a legitimate strategy, and those who fully embrace the morality of terrorist organizations and continue ascending become willing recruits as active terrorists.

There are various tactics used to convince new members to commit to the moral code of the terrorist organization. The most important tactics in this process are isolation, affiliation, secrecy, and fear. Numerous studies of terrorist organizations and their networks reveal that terrorists, alongside their normal public lives, develop parallel lives characterized by complete isolation and secrecy. New members are instructed to keep their parallel lives secret from family members and close friends. The illegal nature of their organization is perceived as harsh governmental repression, and the observed lack of societal openness contributes to their continued isolation, which reinforces feelings of belonging and connection with other group members (Alexander, 2002; Alexander & Swetman, 2002; Rapoport, 2002; Sageman, 2004). Recruitment into terrorist organizations occurs on the fourth floor, where potential terrorists begin to view the terrorist group as legitimate.

Individuals at this stage develop a worldview framed as "us versus them." Once an individual reaches the fourth floor and becomes a recruited member of the terrorist organization, there is no longer an opportunity to leave. According to Moghaddam, recruits become members of cells typically consisting of up to five members, and they only have information about other members within their own cell. Some recruits remain long-term cell members, while others are recruited specifically to become suicide bombers or to carry out violent attacks. The entire process of recruitment, training, and execution of a terrorist act can sometimes be very brief. During this period, the recruit receives considerable positive attention and special treatment. Commitment to the terrorist organization and its goals strengthens over time, as recruits increasingly identify with the traditions and methods of the group. Moghaddam notes that conformity and obedience rank very highly among the values of terrorist cells, and the cell leader represents a strong authority figure where nonconformity, disobedience, and disloyalty are harshly punished (Moghaddam, 1998). Individuals on the fourth floor become aware that they are part of a strictly controlled group from which they can no longer exit, and that the number of doors, i.e., opportunities, has diminished.

Immediately before carrying out a terrorist act, inhibitory mechanisms that prevent violence against others are activated in individuals. Those on the fifth floor are selected and trained to bypass these inhibitory mechanisms. Terrorist organizations consider these inhibitory processes during the training of operatives, and their training is designed accordingly. This type of training includes two psychological processes critical to intergroup dynamics (Brown & Gaertner, 2001). The first involves creating the perception that all individuals outside the organization are enemies, i.e., the social categorization of civilians as part of the out-group. The second involves psychological distancing by exaggerating differences between the in-group and out-group. The use of modern weapons and powerful explosives enables terrorists to destroy targets from a distance, thereby avoiding triggering inhibitory mechanisms.

Moghaddam’s psychological metaphorical model of radicalization can be applied to the case of Mohammed Bouyeri. Born in 1978 in Amsterdam to a family of Moroccan descent, Bouyeri was raised and educated in a secular environment. However, during adolescence, he became increasingly frustrated with social inequality. Following the death of his mother, he withdrew from social life and became increasingly susceptible to extremist ideologies.

Bouyeri adopted a strict interpretation of Sunni Islamic Sharia law, and accordingly altered his physical appearance to reflect these beliefs. Under the pseudonym Abu Zubair, he frequently published radical writings. He also became increasingly active online, where he disseminated pamphlets containing antisemitic and anti-Dutch content. He was a regular attendee at the El Tawheed mosque, where he encountered other radical Sunni individuals, including the suspected terrorist Samir Azzouz. Eventually, he became a member of the Hofstad Network (Dongen, 2015).

Table 2. Application of Moghaddam’s Model to the Case of “Bouyeri”

|

Feelings of social isolation and marginalization; perception of

unfairness.

|

|

Seeing options to combat injustice, which may

foster anger and frustration.

|

|

Assigning blame to an external ‘enemy,’ here

the West and Dutch society.

|

|

Embracing the moral justification offered by

terrorist organizations.

|

|

Belief that violence is a legitimate defense

of one’s faith.

|

|

The murder of a director as an act of jihad.

|

|

An individual—under the influence of social isolation, moral

grievance, and ideological indoctrination—can ascend through all stages of

Moghaddam’s staircase.

|

Source: Authors

Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh produced the film Submission, which depicted Islam as a source of oppression and addressed the issue of violence against Muslim women. Bouyeri interpreted the film as a direct insult to Islam and resolved to kill van Gogh, justifying his actions through religious reasoning. He was subsequently arrested and sentenced to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole (Dongen, 2015).

Silber and Bhatt’s Conceptual Model of Radicalization

Mitchell Silber and Arvin Bhatt analyzed the processes of radicalization in Western contexts with the aim of defining the social and private circumstances under which individuals living in Western societies decide to commit acts of terrorism. According to Silber and Bhatt, the radicalization process consists of four distinct stages: pre-radicalization, self-identification, indoctrination, and jihadization (Silber & Bhatt, 2007:6). The pre-radicalization stage describes the individual's world — including their origin, lifestyle, religion, social status, neighborhood, and education — immediately before beginning their path toward radicalization (Silber & Bhatt, 2007:22). The authors note that in this phase, the psychological profile of the individual and their psychological predispositions for radicalization are not considered, as their conclusions indicate that while many factors influence the process, none of them constitute a psychological weakness or predisposition.

One of the key factors identified is the environment in which the individual exists. In Western countries, Muslim communities tend to be somewhat isolated, which consequently creates a sense of social exclusion in the individual, fostering a need for stronger connection within their own community. Another important factor is the social dimension, including aspects such as age, lifestyle, occupation, and ideology. Considering these factors, commonalities among radicalized individuals become apparent. They are predominantly Muslim males, second or third generation, under the age of 35, and of diverse ethnic backgrounds living in Western countries. Most are educated, with some being highly educated. The majority were neither radical nor particularly devout but experienced a recent conversion. They typically have ordinary jobs and lifestyles and possess virtually no criminal record (Silber & Bhatt, 2007:23).

The second stage, termed the self-identification phase by Silber and Bhatt, is characterized by the influence of both internal and external factors on the individual. Since their research focused on followers of Salafi Islam, the authors explain that in this phase, the individual begins to explore Salafi Islam and gradually distances themselves from their original identity. This phase is often triggered by an event or experience that causes the individual to question their previous beliefs and value system, seeking answers within the new ideology. In their search to resolve their identity crisis, the individual feels the need to find and reconnect with like-minded peers. Subsequently, they progressively reject their old identity and begin adopting a new one, which may be signaled by growing a beard, wearing traditional Islamic clothing, and increasingly attending Salafi mosques. Silber and Bhatt state that at this point, the individual ceases to act as an autonomous individual and instead becomes part of a group sharing the same worldview and value system (Silber & Bhatt, 2007:30).

The third stage, referred to as the indoctrination phase, is marked by the legitimization of violence as a means to achieve the goals of Salafi Islam. Indoctrination involves a progressive intensification of beliefs, whereby the individual fully embraces the jihadist-Salafi ideology and concludes, without doubt, that certain conditions and circumstances necessitate actions in support of the Salafi cause (Silber & Bhatt, 2007:36). Individuals become convinced of the correctness of Salafi teachings, thereby legitimizing the means and methods used to pursue declared objectives. In this phase, individual ideology is replaced by group ideology, and cells are formed.

The authors identified two key indicators of advanced radicalization: mosque abandonment and politicization of new beliefs. Individuals abandon the mosque when their individual level of extremism surpasses that of the mosque community. They begin to perceive the mosque solely as a gathering place for like-minded individuals, and attendance is increasingly seen as a potential obstacle to achieving their objectives, as mosques are often monitored by intelligence agencies. Furthermore, this phase entails the formation of a new identity based on Salafi ideology. The individual begins to perceive the world dichotomously as believers ("us") versus non-believers ("them"), with the latter becoming the primary adversaries. This leads to a radical individual break from the wider world and stronger bonding within the cell of like-minded individuals. The indoctrination phase also features a critical role of the spiritual leader, whose influence fosters a sense of legitimacy regarding the goals among cell members.

The final stage in the radicalization process, according to Silber and Bhatt, is jihadization (Silber & Bhatt, 2007:41). At this stage, cell members seek to contribute actively to jihad, and the cell begins preparations for carrying out a terrorist act. Candidates believe that by doing so, they will be remembered as holy warriors. Individuals become so radicalized that executing a terrorist act is perceived as an individual duty. Some individuals aim from the outset to conduct an independent terrorist attack, while others prefer to act within the framework of the cell.

The target or goal of the terrorist act is usually determined by the cell or its leadership. However, the ultimate objective of every attack remains consistent — to punish the West, overthrow the democratic order, reestablish the caliphate, and implement Sharia law (Silber & Bhatt, 2007:43). The time frame from the mental acceptance of jihad to the execution of a terrorist attack can be very short. During this period, individuals who identify with jihad begin planning and preparing for the attack. This process involves multiple steps. The first step involves the decision to engage in jihad. The next step includes traveling abroad, often to countries considered jihadist hotspots such as Pakistan, Iraq, Afghanistan, Kashmir, and Somalia (Silber & Bhatt, 2007:43). Training or joint preparation follows, during which individuals separate from secular life and spend increasing amounts of time with other cell members, often in group training or collective activities. This fosters strong cohesion within the cell and facilitates coordination for the terrorist act. The subsequent step is planning the attack, which includes reconnaissance, data gathering, role assignment among cell members, and selecting the method of attack. The final step in jihadization is the execution of the terrorist act. By this point, all potential preventive indicators have usually expired. Terrorists have attained the intent, capability, and opportunity to carry out the attack, which intelligence services and other state security mechanisms are now almost unable to prevent (Silber & Bhatt, 2007:46).

After examining the radicalization models of Randy Borum, Fathali M. Moghaddam, Mitchell Silber, and Arvin Bhatt, it can be concluded that all three authors recognize radicalization as a process occurring in phases, stages, or steps. Radicalization unfolds over a certain period and culminates in the commission of a terrorist act. The authors also agree that although an individual may be radicalized to a certain extent, this does not imply that all radicalized individuals are prepared to carry out terrorist attacks. Furthermore, despite the prevalence of the internet and virtual space, self-radicalization is not the dominant form of radicalization. The process is still predominantly shaped by the individual's environment, the group to which they belong, and the overall dynamics and narrative of the community in which they are embedded. Regarding factors driving an individual toward radicalization, the authors identify a sense of injustice and dissatisfaction as key determinants. Additionally, contrary to some opinions, radicalized individuals do not possess psychological predispositions for radicalism and generally exhibit no form of mental pathology. On the contrary, terrorist organizations seek to recruit reliable, obedient, and stable individuals who will act in accordance with organizational decisions. Moreover, despite the common belief that ideology is one of the primary motives for individual radicalization, it can be concluded that ideology may be one of several possible motives but that, in most cases, radicalization results from feelings of individual deprivation or perceived injustice.

Silber and Bhatt’s model can be illustrated through the example of a group of eighteen young men—second-generation immigrants—who were arrested in Canada in 2006 for planning multiple terrorist attacks on Canadian soil. The “Toronto 18” represents a group that underwent radicalization within Canada, emulating the methods and rhetoric of international terrorist networks, despite lacking direct affiliation with them (Nesbit et al, 2021).

Table 3. Application of Silber and Bhatt’s Model to the Case of the Toronto 18 Group

|

Pre‑radicalization

|

Most members grew up in stable families without prior signs of

extremism.

|

|

Self‑identification

|

Identifying with Muslim identity and the problems of the Islamic

world.

|

|

Indoctrination

|

Meetings, listening to radical speakers, watching propaganda videos.

|

|

Jihadization

|

Active preparations for attacks, acquiring explosives, military

training.

|

|

Conclusion

|

The process of radicalization took place within the country, without

direct influence from foreign actors, through four phases, and this model was

applicable to the group. Silber and Bhatt’s model is applicable in the

security sector for early threat detection.

|

Source: Author

The group’s motivations can be understood as rooted in a desire for revenge, stemming from a perceived oppression of Muslims by Western political powers, as well as the suffering of civilians in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Palestine. Canada was viewed as a participant in a global “war against Islam” due to the involvement of Canadian military forces in operations in Afghanistan.

Members of the group adopted radical ideology through exposure to video messages by Osama bin Laden and other extremist figures. A crisis of personal identity led to the internalization of an extreme group identity, which offered them a sense of belonging, purpose, and a binary worldview dividing the world into “us versus them.” Due to a tip-off regarding the group’s plans, the members were apprehended before they could carry out any terrorist acts.

The Deradicalization of Adherents to Extremist Ideology

While radicalization is defined as the act or process of guiding or directing an individual toward adopting radical views on political or social issues, deradicalization is the process of changing an individual’s beliefs, rejecting extremist ideology, and re-embracing broader societal values (Bubolz & Simi, 2015).

Although the terms disengagement and deradicalization are often used synonymously in the sense of separating a radicalized individual from a radical group, they represent two distinct social and psychological processes. Disengagement refers to a behavioral change, such as leaving the group or changing one’s role within the group. Disengagement does not imply abandoning values or ideals but is generally characterized in the literature as including an (emotional) distancing from the use of violence to achieve goals (Fink & Haerne, 2008:3). Deradicalization, however, entails either an emotional or cognitive process. Emotional deradicalization is often triggered by a traumatic experience that challenges the radical worldview (Fink & Haerne, 2008:4). According to Koehler, deradicalization represents a behavioral change in terms of renouncing violence but simultaneously involves a cognitive distancing from criminal, radical, or extremist beliefs toward a non-criminal or moderate psychological state (Koehler, 2017:2). John Horgan similarly emphasizes that deradicalization includes both physical and mental changes in the individual (Horgan, 2008:8). However, Koehler stresses that disengagement without deradicalization increases the likelihood of recidivism, especially in the case of religiously motivated terrorists, who tend to relapse and return to violent behavior (Koehler, 2017:14).

Approaches and methods used for deradicalization largely depend on the underlying reasons for which the individual was radicalized in the first place, as well as on how the radicalization occurred (Fink & Haerne, 2008:37). When referring to emotional deradicalization, this concerns the emergence of certain attitudes in the radicalized individual that, sometimes due to the aforementioned traumatic experience, distance them from the radical ideology. Primarily, this relates to the individual’s disillusionment with the actions, goals, and values promoted by the radical group, which they were unaware of when joining the group. On the other hand, cognitive deradicalization involves the individual’s rational realization that the actions, goals, and values of the radical group are unacceptable and ineffective means of achieving any objective. Emotional and cognitive deradicalization are not mutually exclusive. However, emotional deradicalization often occurs unintentionally, whereas cognitive deradicalization is often a planned process in which other individuals or institutions play an important role (Horgan et al., 2017).

Deradicalization programs implemented in some European countries primarily focus on providing support and assistance to youth who seek to disengage from extremist groups, offering aid to their families, and educating professionals who are actively involved in addressing this issue at the societal level. In Middle Eastern countries, deradicalization efforts are largely based on rehabilitation programs for followers of extremist groups, conducted in cooperation with experts, alongside widespread public information campaigns that explicitly highlight the effects of violence on victims (Horgan et al., 2017:9).

Furthermore, some studies indicate that institutional deradicalization can sometimes be effective but at other times may fail to produce desired outcomes (Lindekilde, 2014). Specifically, aggressive attempts by security and police forces to prevent radical activities and combat radical groups, although often positively received and perceived by the public, can occasionally deepen radicalization processes and potentially push marginalized individuals toward more extreme behaviors (Lindekilde, 2014:10).

From this, it follows that when developing effective intervention programs to counter radicalization, a careful balance must be struck between “hard” punitive measures and “soft” reintegration interventions. Intervention programs also include raising public awareness about online radicalization and educating families and friends about possible signs of radicalization, which can aid in early-stage prevention. Additionally, a public discourse promoting inclusivity and reintegration, along with the establishment of centers for psychological support, can provide positive incentives for radicalized individuals who seek deradicalization.

Beyond these measures, the literature offers a range of other intervention strategies to prevent radicalization. However, it is important to acknowledge that no single model is universally applicable to every radicalized individual or to any specific radical ideology. Nevertheless, a thorough understanding of scientifically grounded deradicalization models and their respective advantages and limitations is essential for selecting the most appropriate approach.

Horgan's Model of Deradicalization

John Horgan, a leading scholar in the psychology of terrorism, has made a significant contribution to the understanding of the deradicalization process through his differentiation between the two related but distinct concepts of disengagement and deradicalization (Horgan, 2008). While he has also conducted important research on the causes and pathways of radicalization, which form the foundation of his further work, his most notable contribution lies in the study of deradicalization of extremist ideology followers.

Horgan explains that disengagement can result from individual or collective processes, or a combination of both. It may arise from various experiences such as changes in role, shifts in attitudes, and can—but does not necessarily—lead to a change in mindset (Horgan, 2008:5). However, Horgan argues that disengagement does not necessarily equate to deradicalization. Based on his research with perpetrators of terrorist acts, he concludes that in certain cases, although there may be physical withdrawal from terrorist activities, this does not correspond to a genuine abandonment of ideological support, nor does it weaken the social and psychological control that a given ideology exerts over the individual (Horgan, 2008:6).

Horgan’s model is based on a psychological and behavioral approach, focusing on individual motivations and environmental factors influencing the disengagement from extremist groups (Horgan, 2009; Horgan, 2014). Radicalization and deradicalization are thus not viewed solely as ideological processes but rather as dynamic psychosocial phenomena arising from the interaction between individual motivations and external environmental conditions (Horgan, 2009; Horgan, 2014). This model assumes that individuals do not join extremist groups solely because of ideological beliefs but also due to emotional and social needs, such as a sense of purpose, identity, and belonging.

From a psychological perspective, Horgan (2009) emphasizes the importance ofindividual frustrations, emotional voids, and experiences of marginalization as factors that can motivate entry into, but also exit from, radical groups. For example, disillusionment with the ideology, political goals, or operational tactics, loss of trust in ideological leaders, or shifts inindividual priorities may trigger the disengagement process (Horgan, 2008:4). Simultaneously, feelings of shame, guilt, or emotional exhaustion often emerge as important psychological catalysts for withdrawal.

From a behavioral standpoint, Horgan highlights that many deradicalization programs achieve success primarily through behavioral changes, not necessarily requiring a complete ideological shift. Behavioral changes often result from concrete environmental influences, such as pressures from the justice system, family relationships, changes in the structure of the extremist organization, or practical barriers to continuing extremist activities (Horgan, 2008:5; Horgan, 2014). This approach allows for an individualized understanding of the deradicalization process, avoiding assumptions of a universal pattern, and instead analyzing each case in light ofindividual and contextual factors.

Consequently, Horgan’s model contributes to the development of flexible and realistic intervention programs that, rather than relying on coercion or ideological indoctrination, provide social, emotional, and practical support (Horgan, 2009). In this context, the model relies heavily on qualitative methods, such as in-depth interviews, to understandindividual reasons for leaving violent extremism without forcing changes in belief, emphasizing that disengagement may be a more realistic and measurable goal than complete deradicalization (Horgan, 2014).

Moreover, Horgan stresses the importance of offering alternative identities, goals, and senses of belonging to former members of extremist groups. He advocates for the development of individualized intervention approaches, including counseling, education, professional rehabilitation, and community reintegration (Horgan, 2009). Within this framework, program effectiveness is measured not solely by changes in beliefs but also by long-term prevention of relapse into violent behavior.

Empirical research inspired by Horgan’s model has demonstrated that emotional, practical, and social factors play a crucial role in the process of disengagement from extremism (Barrelle, 2015; Bjørgo & Horgan, 2009). Thus, this model represents an important theoretical and operational framework for understanding and designing deradicalization strategies in various contexts, including penal institutions, programs for returning foreign fighters, and civil society initiatives.

Horgan’s deradicalization model has been applied in diverse national contexts, such as programs in Saudi Arabia, Germany, Denmark, and Sweden, where it has served as a foundation for developing individualized rehabilitation and reintegration strategies for former extremists (Boucek, 2008; Bjørgo & Horgan, 2009; El-Said, 2015; RAN, 2017). These countries emphasize understanding the psychological and social needs of individuals rather than focusing solely on ideological conversion, consistent with Horgan’s theoretical propositions. The application of Horgan’s model in different national settings illustrates how theoretical frameworks can inform the development of effective programs tailored to specific cultural, political, and security conditions (El-Said, 2015). A key feature of all successful practices based on this model is their focus on individualized approaches, the differentiation between cognitive change and behavioral change, and the provision of alternative social and professional identities.

John Horgan’s deradicalisation model has significantly advanced the understanding of the psychological and behavioural dimensions of disengagement from extremism; however, it is not without limitations. A primary critique concerns its predominant focus on individual motivations and psychological factors, which may underemphasize the broader structural, political, and socio-economic contexts that shape radicalisation and deradicalisation processes. While the model rightly highlights the importance of emotional needs and personal grievances, it sometimes lacks a comprehensive integration of external influences such as community dynamics, state policies, or ideological shifts at the macro level. Moreover, Horgan’s emphasis on behavioural change as a pragmatic goal may overlook the enduring ideological commitments that persist despite disengagement from violent activities, thus potentially underestimating the risk of recidivism.

The model’s reliance on qualitative, interview-based data, while rich in depth, limits its generalizability across diverse populations and extremist movements. Additionally, the model offers limited operational detail regarding the implementation of intervention programs, making it challenging for practitioners to translate theoretical insights into consistent, scalable deradicalisation strategies. These weaknesses suggest a need for a more holistic approach that balances psychological individualism with contextual and structural complexities.

Koehler's Model of Radicalization and Reintegration

In his extensive research, Daniel Koehler developed a typology of deradicalization programs, identifying seven distinct categories (see Table 1). These program types differ in their objectives, methodologies, and institutional frameworks. However, Koehler emphasizes that all effective deradicalization initiatives share key characteristics: they must target individuals or groups who self-identify as radical, possess clearly defined goals primarily focused on the reintegration of participants into society, and explicitly reject the use of violence as a means to achieve their objectives (Koehler, 2017, p. 112).

Table 4. Typology of deradicalization programs according to Koehler

Source: Authors

Koehler’s model, which underpins each of the aforementioned deradicalization programs depending on their specific objectives, methods, and institutional contexts, represents one of the most systematic and operational approaches to countering violent extremism in Europe. This model is grounded in a structured, multidisciplinary, and individually tailored approach, emphasizing practical institutional support, family involvement, and the reintegration of individuals into society (Koehler, 2017).

Similar to many other theorists, Koehler incorporates an analysis of the factors that initially led to an individual's radicalization and bases his conclusions on empirical research conducted with former members of radical organizations. He argues that identifying and understanding both the drivers of radicalization and the factors that facilitate deradicalization should form the foundation of individualized strategies for disengagement. Such an approach can contribute not only to the deradicalization process itself but also to the successful social reintegration of the individual.

However, Koehler stresses the importance of considering inhibitory factors that may impede the abandonment of radical ideology or terrorist organizations during deradicalization efforts (Koehler, 2017, p. 20). The primary inhibitory factors stem from negative sanctions imposed by the group itself, often manifesting as pressures on members to withhold information from outsiders, adhere strictly to internal organizational rules, and refrain from leaving the group. Any behavior perceived as betraying the group’s trust can trigger sanctions, which must be carefully accounted for when designing individualized intervention approaches (Koehler, 2017, p. 20).

Additionally, Koehler’s model highlights the critical role of institutional infrastructure and coordinated support systems. The deradicalization process, in this framework, is not confined solely to ideological change but encompasses a broad spectrum of factors ranging from psychological support and education to employment and social integration (Koehler, 2019). While the degree of institutional involvement varies depending on the specific program, Koehler emphasizes the necessity of collaboration among non-governmental organizations, security institutions, and the academic community.

One of the most notable implementations of Koehler’s model is the HAYAT program, which adopts the multidisciplinary approach he advocates. The program works not only with radicalized individuals but also engages their families, communities, and society at large to facilitate reintegration and reduce the risk of recidivism (Koehler, 2013, p. 182).

Ultimately, the strength of Koehler’s model lies in its capacity to integrate a theoretical understanding of radicalization with practical and measurable intervention methods. This integration enables a balanced approach that acknowledges individual motivations while situating them within a broader social and institutional framework.

Daniel Koehler’s deradicalisation model is widely recognized for its comprehensive, multidisciplinary, and institutional approach; nonetheless, several limitations have been identified in the literature. One key weakness lies in the model’s heavy reliance on well-resourced institutional frameworks and extensive inter-agency cooperation, which may not be feasible or replicable in contexts with limited political will, funding, or institutional capacity. This raises concerns about the model’s scalability and applicability beyond Western European settings where it was primarily developed and tested. Furthermore, while Koehler emphasizes the importance of individualized strategies and the role of inhibitory social factors within extremist groups, the model can understate the complexity of ideological transformations, sometimes prioritizing behavioral reintegration over deeper cognitive shifts. Critics also note that the model’s focus on institutionalized interventions may marginalize grassroots or community-led efforts that could be equally vital in deradicalisation processes. Finally, despite advocating for comprehensive evaluation mechanisms, empirical evidence on the long-term effectiveness of Koehler’s programs remains limited, highlighting the need for more rigorous longitudinal studies to substantiate its practical outcomes. These challenges suggest that, although Koehler’s framework offers a valuable foundation, it requires adaptation and contextualization to diverse environments to enhance its effectiveness. Therefore, key challenges in implementing this model include the need for highly trained professionals, securing financial and political support, and ensuring long-term monitoring and evaluation of program effectiveness. Despite these challenges, Koehler’s model stands as one of the most comprehensive solutions in the European context and has served as a blueprint for programs in other countries such as Austria, Sweden, and the United States (Koehler, 2017; Koehler & Fiebig, 2019).

Conclusion:

Radicalization is a complex process influenced by various psychological and emotional factors that can render an individual susceptible to extremist ideologies. Recent literature increasingly highlights online radicalization as a growing concern, primarily due to its far-reaching impact beyond the scope of national security agencies, as well as its broad influence—particularly among young people. While top-down recruitment is the form most frequently emphasized in studies focusing on Islamist extremist organizations, bottom-up radicalization refers to a process whereby individuals independently initiate their involvement with violent extremist groups. It is indisputable that extremism, violent extremism, and terrorism represent some of the most significant security challenges of the contemporary era. Consequently, it is unsurprising that security and intelligence agencies across developed countries dedicate substantial efforts toward identifying and preventing violent extremist and terrorist acts. Furthermore, intervention strategies aimed at preventing radicalization, promoting deradicalization, and facilitating the reintegration of radicalized individuals into society are being developed at both national and international levels. For these intervention and deradicalization efforts to be effective, further work is required to deepen the understanding of the underlying social and emotional drivers of radicalization. A comparative analysis of the examined models is presented in Table 5.

The summary of three prominent theoretical models of radicalization—Borum’s, Moghaddam’s, and Silber-Bhatt’s—addresses distinct aspects of the process leading individuals to engage in terrorist activities. Borum conceptualizes radicalization as a four-stage process in which ideology is not the sole driver; instead, social and emotional factors such as inequality, grievance, and enemy demonization are emphasized. He argues that understanding behavior and motivations is crucial for effective attack prevention. There are also certain limitations associated with this model. The first is its linear approach to the process of radicalization. In reality, radicalization is often non-linear, unfolding under the influence of multiple and interrelated factors—cultural, economic, and social. Furthermore, the model lacks predictive capacity; that is, even when individuals progress through the stages outlined by the model, there are no clear indicators that they are prepared to commit an act of terrorism.

Additionally, the model places primary emphasis on individual psychological processes, while largely overlooking the influence of the broader social environment. Ultimately, one can conclude that Borum’s model provides a useful framework for understanding the psychological mechanisms that may lead to violent extremism. However, a comprehensive understanding of the radicalization process would benefit from the inclusion of other models that integrate the diverse range of factors influencing radicalization.

Moghaddam, for example, employs the “staircase to terrorism” metaphor to illustrate the psychological and moral dynamics that lead individuals upward toward the final stage—the terrorist act. He emphasizes that only through reforming the “ground floor” of society, that is, by addressing structural injustices, can terrorism be effectively prevented. The limitations of this model are largely similar to those of Borum’s; however, it should be noted that Moghaddam places somewhat greater emphasis on the interplay between psychological and social factors.

Silber and Bhatt, analyzing five terrorist attacks in the West, propose a four-stage radicalization model, emphasizing that the process does not necessarily culminate in violence. They link radicalization to jihadist-Salafi ideology while underscoring the influence of individual and social factors, dismissing psychological predispositions as primary causes. Collectively, these theories underscore the complexity of radicalization, highlighting the interplay between individual, ideological, and social elements that create diverse pathways to extremism.

In conclusion, the analysis of these three theoretical models reveals the multilayered and complex nature of the radicalization process preceding individuals’ involvement in terrorism. Although their approaches differ, all authors stress the importance of understanding the broader context in which radicalization occurs. Borum rejects ideology as the exclusive cause, emphasizing social and emotional dimensions; Moghaddam presents radicalization through symbolic “stairs” gradually ascended under psychological and moral influences; Silber and Bhatt offer a concrete model based on case analyses that stress gradual radicalization, the role of Salafi ideology, and contextual and individual circumstances. One of the key limitations of this model lies in its context-specific applicability—it offers a framework that is particularly tailored to understanding radicalization within Western societies, while its relevance and applicability to non-Western contexts remain limited.

The model does not sufficiently account for the distinct cultural, political, and historical dynamics that shape radicalization processes in other parts of the world, thereby reducing its explanatory power in more diverse global settings. All models agree that radicalization is not automatically linked to terrorist acts but is a process in which individual, ideological, and social factors interact. Hence, comprehending these interactions is essential for timely recognition, prevention, and countering radicalization, thereby safeguarding social security.

Table 5. Comparative Analysis of Borum’s, Moghaddam’s, and Silber & Bhatt’s Models of Radicalization

Source: Authors

Given that each model possesses certain strengths as well as limitations, it would be advisable to combine them with other models that account for environmental influences and broader societal factors in the process of radicalization. Such an integrated approach allows for a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding, acknowledging not only individual psychological mechanisms but also the complex interplay of social, cultural, political, and economic dynamics that shape pathways to radicalization.

Horgan’s deradicalization model is grounded in psychological and behavioral approaches, highlighting the roles of individual motivations, emotional needs, and environmental factors in leaving extremist groups. Contrary to purely ideological explanations, Horgan posits that individuals join and exit radical groups not solely due to ideological convictions but also due to needs for purpose, belonging, or disillusionment. His model distinguishes between cognitive and behavioral change, emphasizing concrete behavioral shifts as a more attainable objective. Deradicalization, in this view, relies not on coercion but on individualized interventions such as counseling, education, and reintegration.

Koehler’s deradicalization model stands as one of Europe’s most systematic and operational frameworks, built on a multidisciplinary, individualized, and institutionally supported foundation. Key components include analyzing the causes of radicalization, involving families, providing psychological support, and facilitating social reintegration. Koehler highlights the significance of inhibitory factors—such as internal group pressures—that may prevent disengagement from extremist ideology. His model incorporates collaboration between NGOs, security agencies, and academia. The practical application of Koehler’s approach is most visible in Germany’s HAYAT program, which works with radicalized individuals and their families. The model’s focus extends beyond mere belief change to broader institutional support encompassing education, employment, and social integration. A comparative analysis of the reviewed models is presented in Table 6.

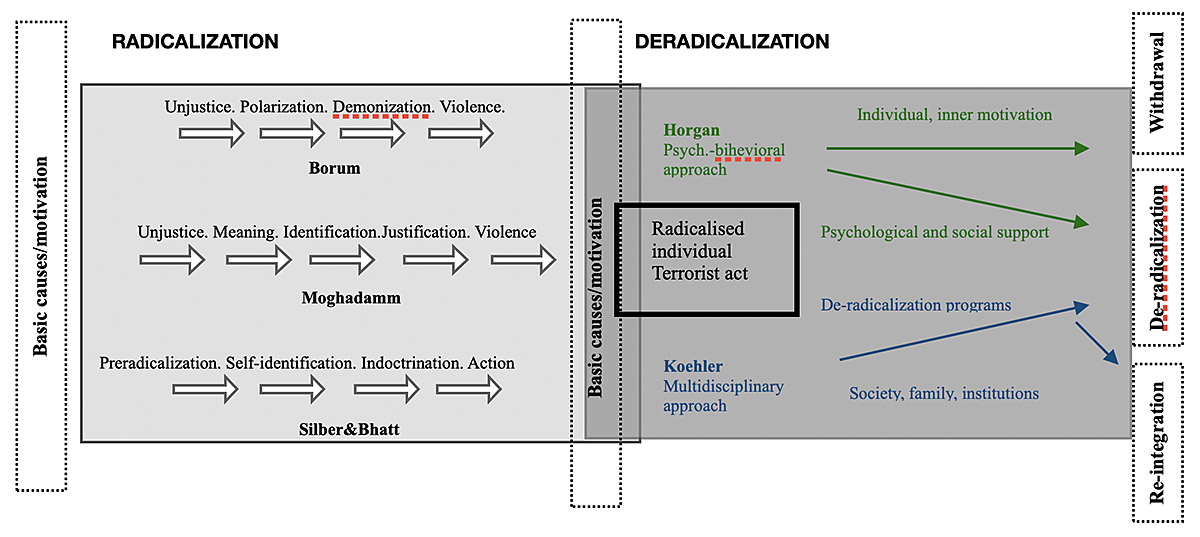

A comparative analysis of radicalization and deradicalization models reveals that, although these processes may initially appear oppositional, they are in fact complementary and interdependent, as illustrated in the model presented in Figure 1. Key areas of overlap include understanding individual motivations, the role of identity, the need for belonging, experiences of marginalization, and the importance of social context. Whether concerning entry into extremist groups or disengagement from them, psychological, social, and environmental factors play a crucial role. Furthermore, most theoretical models emphasize that neither radicalization nor deradicalization are linear or universal processes; rather, they are complex and dynamic phenomena that require individualized approaches.

Table 6. Comparison of Horgan’s and Koehler’s Deradicalization Models

Source: Authors

Figure 1. Radicalization and Deradicalization of Adherents to Extremist Ideologies

Source: Authors

Determining a single “best” model for radicalization and deradicalization proves inherently problematic due to the multifaceted and context-dependent nature of these processes. Each theoretical framework offers distinct advantages and limitations, reflecting different emphases on psychological, social, ideological, or structural factors. As the comparative analysis indicates, radicalization and deradicalization are neither linear nor universal phenomena; they are dynamic, complex, and deeply influenced by individual motivations, identity constructs, social belonging, and contextual circumstances. Consequently, no one model can comprehensively address the full spectrum of factors involved in every case. Instead, the selection of an appropriate model must be guided by the specific characteristics of the target population, the nature of the extremist ideology, and the broader sociopolitical environment. This tailored application allows practitioners and policymakers to leverage the strengths of each model while mitigating their respective weaknesses, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of interventions aimed at both preventing radicalization and promoting deradicalization.

This article contributes to contemporary security studies by providing a comprehensive analysis and comparison of prominent theoretical models of radicalization and deradicalization, thereby enhancing the understanding of the complex psychological and social mechanisms underpinning violent extremism. By critically evaluating the strengths and limitations of each model, the article highlights the necessity of integrating multidisciplinary perspectives to more effectively address the multifaceted nature of radicalization processes. Furthermore, the findings underscore the importance of contextualizing radicalization within diverse sociopolitical environments, which remains underexplored in current scholarship. Future research could fruitfully explore the dynamic interplay between individual psychological factors and broader structural influences, as well as examine the applicability of these models across different cultural and geopolitical contexts, thereby advancing more tailored and effective counter-radicalization strategies.

Future research guidelines should also prioritize longitudinal studies that track individuals throughout the entire cycle of radicalization and deradicalization, thereby enhancing the understanding of the interplay between these phases. Furthermore, there is a pressing need for in-depth investigation of contextual specificities—such as cultural, political, and institutional factors—that influence the effectiveness of intervention programs. Particular attention should also be directed towards the development of robust evaluation tools to measure the success of deradicalization initiatives, with an emphasis on long-term reintegration outcomes. Finally, an interdisciplinary approach that integrates psychology, sociology, security studies, and political science remains essential for comprehensively understanding and effectively addressing both sides of the process.

Literature:

1.Alhendavi, A. (2016). UN Secretary General’s Envoy on Youth: Preventing violent extremism and radicalization of youth.

2.Bakker, E. (2006). Jihadi Terrorists in Europe: Their Characteristics and the Circumstances in Which They Joined the Jihad; An Exploratory Study, Clingendael: Netherlands Institute of International Relations

3.Barrelle, K. (2015). Pro-integration: Disengagement from and life after extremism. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, 7(2), 129–142.

4.Bjørgo, T., & Horgan, J. (Eds.). (2009). Leaving Terrorism Behind: Individual and Collective Disengagement. London: Routledge.

5.Borum, R. (2003). Understanding the Terrorist Mindset. Mental Health Law & Policy Faculty Publications.

6.Borum, R. (2012). Radicalization into Violent Extremism II: A Review of Conceptual Models and Empirical Research. Journal of Strategic Security 4(2).

7.Boucek, C. (2008). Saudi Arabia’s Soft Counterterrorism Strategy: Prevention, Rehabilitation, and Aftercare. Carnegie Papers, Middle East Series. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

8.Brown, R, Andrew, T. C. ,Helmus, R. R., Alina I., Palimaru, S., Weilant, A. L., Rhoades, & Hiat L. (2021). Violent Extremism in America: Interviews with Former Extremists and Their Families on Radicalization and Deradicalization, Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, RR-A1071-1.

9.Bubolzb B. & Simi, P. (2015). Leaving the World of Hate: Life-Course Transitions and Self-Change. American Behavioral Scientist, 59(2).

10.Dongen, T. W. (2015). The science of fighting terrorism: The relation between terrorist actor type and counterterrorism effectiveness (Doctoral dissertation, Leiden University). Leiden University Repository.

11.Duţu, D. (2021). Deradicalization: Between Theory and Practice. Strategic Impact, 81(4), 33-46.

12.El-Said, H. (2015). New Approaches to Countering Terrorism: Designing and Evaluating Counter Radicalization and De-radicalization Programs. Palgrave Macmillan.

13.Fink, N. & Haerne E. (2008). Beyond Terrorism: Deradicalization and Disengagement from Violent Extremism. International Peace Institute.

14.Gill, P., Clemmow, C., Hetzel, F., Rottweiler, B., Salman, N, Van der Vegt, I., Marchment, Z., Schumann, S. (2021). Systematic Review of Mental Health Problems and Violent Extremism. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, 2(1).

15.Helfstein, S. (2012). Edges of Radicalization: Ideas, Individuals and Networks in Violent Extremism. The Combating Terrorism Center West Point.

16.Horgan, J. (2008). From Profiles to Pathways and Roots to Routes: Perspectives from Psychology on Radicalization into Terrorism. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 618(1), 80–94.

17.Horgan, J. (2009). Walking Away from Terrorism: Accounts of Disengagement from Radical and Extremist Movements. London: Routledge.

18.Horgan, J. (2014). The Psychology of Terrorism (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

19.Horgan J., Altier, M., Shortland, N. & Taylor, M. (2017). Walking Away: The Disengagement and De-Radicalization of a Violent Right-Wing Extremist. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, 9(2), 1-15

20.Horgan, J. (2018). Deradicalization or Disengagement? A Process in Need of Clarity and a Counterterrorism Initiative in Need of Evaluation. Perspectives on Terrorism, 2(4), 3-8.

21.Jensen, M., LaFree, G., James, P.A., Atwell-Seate, A., Pisoiu, D., Stevenson, J., & Tinsley, H. (2016). Empirical Assessment of Domestic Radicalization (EADR). College Park: National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, University of Maryland.

22.Jensen, M., James, P., LaFree, G., Safer-Lichtenstein, A., & Yates, E. (2018). The Use of Social Media by United States Extremists. College Park: National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism. University of Maryland.

23.Jensen, M., Yates, E. & Kane, S. (2020). Research Brief: Profiles of Individual Radicalization in the United States.

24.Jensen, M. (2024). Profiles of Individual Radicalization in the United States (PIRUS) 1948-2014. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2024-03-13. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR36309.v2

25.Koehler, D. (2013). Family counselling as prevention and intervention tool against 'foreign fighters': The German 'Hayat' program. Journal EXIT-Deutschland, 3, 182–204.

26.Koehler, D. (2015). Family counseling as prevention and intervention tool against “foreign fighters”: The German “Hayat” program. Journal for Deradicalization, 1(3), 63–106.

27.Koehler, D. (2017). Understanding Deradicalization: Methods, Tools and Programs for Countering Violent Extremism. Routledge.

28.Koehler, D. (2019). Right-Wing Terrorism in the 21st Century: The “National Socialist Underground” and the History of Terror from the Far-Right in Germany. Routledge.

29.Koehler, D., & Fiebig, H. (2019). Assessing Interventions to Counter Violent Extremism and Radicalization: Evidence from Germany. International Journal of Conflict and Violence, 13(1), 1–13.

30.Koehler, D. (2020). A Typology of "Exit" Programs in Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism. In M. S. Elshimi, S. D. Winterbotham & D. Koehler (Eds.), Countering Violent Extremism: Making Gender Matter (pp. 23–37). Palgrave Macmillan.

31.Lindekilde, L. (2014). A Typology of Backfire Mechanisms u Bosi, L., Demetriou, C. & Malthaner, S. eds., Dynamics of Political Violence: A Process-Oriented Perspective on Radicalization and the Escalation of Political Conflict. London: Routledge.

32.Moghaddam, F.M. (2005). The Staircase to Terrorism - A Psychological Exploration. American Psychologist, 60(2), 161-169.

33.Muro, D. (2016). What does radicalisation look like? Four visualisations of socialisation into violent extremism. Notes internacionals.

34.National Institute of Justice (2018). Research Provides Guidance on Building Effective Counterterrorism Programs.

35.Nesbitt, M., Roach, K., Hofmann, D. C., & Lee, K. (2021). Canadian terror: Multi‑disciplinary perspectives on the Toronto 18 terrorism trials. Manitoba Law Journal, 44(1)

36.Oxford University Press (2020). Definition of Extremism in English.

37.Sageman, M. (2008). Leaderless Jihad: Terror Networks in the Twenty-First Century. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

38.Silber, M.D. & Bhatt, A. (2007). Radicalization in the West:The Homegrown Threat. New York.

39.Radicalisation Awareness Network (RAN). (2017). The returnee challenge: Demobilising and reintegrating foreign terrorist fighters and their families. European Commission.

40.Rabasa, A., Pettyjohn, S. L., Ghez, J. J., & Boucek, C. (2010). Deradicalizing Islamist extremists. RAND Corporation.

41.U.S. Department of Homeland Security (2018). Snapshot: S&T Develops the First Line of Defense Against Acts of Targeted Violence. August 28, 2018.

42.Vandor A. (2020). Manifestation of Hateful Conduct to Radical Extremism as a Threat to the Canadian Armed Forces. Canadian Forces College JCSP 47 – PCEMI 47.

43.Vecchioni, M. (2018). How does one become a terrorist and why: Theories of radicalization. Sociology of Terrorism. Doctoral dissertation.

44.Weine S. & Osman A. (2012). Building Resilience to Violent Extremism Among Somali-Americans. College Park: National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, University of Maryland.

45.Wiktorowicz, Q. (2005). Radical Islam rising: Muslim extremism in the West. Rowman & Littlefield.

46.Zmigrod, L., Rentfrow, P.J., & Robbins, T.W. (2019). Cognitive Inflexibility Predicts Extremist Attitudes. Frontiers in Psychology, 10.

Cite this article:

APA 6th Edition

Pokrajčić, I. i Marinić-Kuliš, T. (2025). Comparative Analysis of Theoretical Models of Radicalization and Deradicalization of Extremist Ideology Followers. National Security and the Future, 26 (2), 19-70. Preuzeto s https://hrcak.srce.hr/334470

MLA 8th Edition

Pokrajčić, Ivana i Tina Marinić-Kuliš. "Comparative Analysis of Theoretical Models of Radicalization and Deradicalization of Extremist Ideology Followers." National Security and the Future, vol. 26, br. 2, 2025, str. 19-70. https://hrcak.srce.hr/334470. Citirano DD.MM.YYYY.

Chicago 17th Edition