Author: Prof. Zoran Milosavljević, Institute for Political Studies, Belgrade, Serbia

DOI: https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.26.1.6

Review paper

Received: April 17, 2025

Accepted: April 30, 2025

Abstract: The present article deals with the transition period in Serbia in the period from 2000 to the present. Institutional reforms and the endemic occurrence of corruption at all levels are concomitant phenomena of this period. The authors try to provide answers to certain questions concerning: the causes of weak institutions in the transition period of Serbia, the possibilities of strengthening the institutions, the explanation of corrupt behavior and the lack of legislation in the supporting segments of public and economic life. The general hypothesis suggests that weak institutions and corruption are in correlative relationship: weak institutions cause greater corruption, and vice versa,

stronger institutions suppress corruption. In scientific terms, this article seeks to provide answers to basic questions about the relationship of institutions and corruption, to describe the status of the studied phenomena (corruption and weak institutions) in the transition period of Serbia and to offer solutions for the problem situation. The social relevance of this study would be: identification of the problems, pointing to their harmful, and even fatal, consequences to the society and its population and, thus, contributing to the overcoming the criticality of present situation.

stronger institutions suppress corruption. In scientific terms, this article seeks to provide answers to basic questions about the relationship of institutions and corruption, to describe the status of the studied phenomena (corruption and weak institutions) in the transition period of Serbia and to offer solutions for the problem situation. The social relevance of this study would be: identification of the problems, pointing to their harmful, and even fatal, consequences to the society and its population and, thus, contributing to the overcoming the criticality of present situation.

Keywords: corruption, transition, weak institutions, financial crime, organized crime, Serbia

Introduction

The transition period between the socialist system of government and political economy towards the liberal democracy regime based on the postulates: free elections, market economy and the rule of law is colloquially referred to as "transition" (Linz & Stepan, 1996). In the process of transition, numerous institutional shortcomings have arisen, so called "system gaps" that led to the creation of institutionalized legal gaps that allowed corruptive action. These are unhindered social behaviors that by "systemic anomalies" encourage the anomalous states of social entropy (Zindović and Stanković, 2012). These state regulations erode and destroy the political, legal and economic system of the country.

For this reason, it is very important to analyze the findings and the state of institutional forms of corruption in the Republic of Serbia in the process of transition from one political-economic system to another. In this paper will be analyzed: social, political and economic factors of corruption. Therefore, corruption is defined as institutionalized, stable social behavior, which most often does not have a foothold in the legal regulation (Breen & Gillenders, 2012).

Institutional Forms of Corruptive Activity

The author tries to approach the research subject from several methodical angles, to encompass the phenomenon in a more comprehensive extent, using descriptive approach, observation method, content analysis, comparative method and institutional approach. A particularly noteworthy place will have logical approaches: induction and deductive conclusion, and particularly the dialectical method of institutions' relations towards corruption.

For the purposes of this paper, the following corruption manifestations will be included in the institutional forms of corruption:

- Corruption through social relations;

- Political corruption;

- Economic corruption;

- Legal corruption; and

- Social corruption.

Corruption through social relationship

Institutional forms of corruptive activities in the domain of interpersonal relations, which are the result of established evaluations among the actors of social relations (value, attitudes and behavior), have the following characteristics in the Republic of Serbia:

- Serbia is a relatively small community of people. Social actors institutionally depend one from the other. This dependence interferes with the construction of modern forms of impersonal relationships that speed up and accelerate institutionalization.

- Social relations are based on parentelism, nepotism, clientelism:

- Paternalism or parentalism denotes the rule of gerontocracy. The oldest generations here are guar-dians of the social order. (There are frequent chan-ges in the laws that allow employment in the most elite professions even in the eighth decade of life). All social and political power is concentrated in the hands of the most influential seniors.They are entru-sted not only with control functions in society, but also with personnel policy. Based on unlimited will of this social group, they carry out the careers of human resources, thus acquiring the exclusive right to determine progress in several social strata (the so-called "elite passage");

- Nepotism is a system of birth relationships where decision-makers appoint officers mostly based on "native origin" (Sherman, 1980). No objective crite-ria govern here, but arbitrariness is based on family and homeland recommendations. Most often, this form of decision-making is not explained, and when it is, then it is justified by the stereotypes: that peop-le from that region are "obedient and cultivated" or "courageous and brave", or simply the government in this way "is repaying a service to a family of merit ";

- Clientelism is in direct relation with paternalism. It is a kind of relationship of dominance and subordi-nation between patron and client, superior and supe-rior. The client must at any time be at the service of his patron, aware of his subordinate status. The su-perior appoints his clients who grow and develop, and in time they pay off the patron for appointment. Thus, the patron with the increasingly branched network of clients strengthens within the system, building oligarchy. Clients are under patrons perso-nal authority if active in any service, sometimes even after death. Then clients have a moral obligati-on and a debt postmortem nobis towards the family of the patron (Stanković & Perić-Diligenski, 2023).

- Alienated centers of power due to bureaucratization of functions act according to the principle: do ut des ("I give to you so that you may give something to me in return") and do ut facere ("I give to you so that you would do something for me in return"). Every social entity seeks to build its personal shop, "store" or "boutique" and offer its good services to others in the process of exchange and counter service. (Cvejić, 2016). This is a parallel invisible world of connections and interests that institutions use only and exclusively as an external mask for personal and enrichment. In the process of exchange, the social actor strengthens his private position, using the public resource. He performs a public function only as much as he must (and for how much he is paid). The rest of the time, and all other energy, the social actor redirects to his own "shop" or "store" which grows over time. In this case, a public institution will remain only an empty shell that does not develop; in this case, the social actor (or "owner of the shop") uses it as a trusted "fief”.

- An individual, therefore, often receives public authority, to develop it and improve it. The entrusted public authority is treated as its own "prey" and "fief" by privatizing it, thus extracting certain titular rights from it: usufruct, official duties, sometimes even the right to lease. By grafting legal burdens of the things managed by him, he redirects public resources into his private "shop", thereby strengthening his own property.

- Constituent behavior is often based on personal non-institutional relationships. They are deprived of legal procedures that involve impartial forms of normative behavior equal to all.

- In parallel with institutionalized forms of social traffic there are personal contacts, connections and acquaintances. Institutional traffic is replaced by private contacts.

Political corruption

Forms of political corruption include:

- Partiocratic order of power. One example: social power is channeled exclusively through political parties. The second example of the same phenomenon suggests that there is a danger of "buying political decisions" (Milosavljević & Krstić, 2012), which further facilitates corrupt activities.

- The dominance of the ruling party over other parties. Example: The ruling party easily and almost without resistance master’s all the major resources in the country: media space, institutions, regulatory bodies, civil sector ... The ruling party strives to destroy its political competition, thereby indirectly destroying the country's political system, weakening its institutions.

- Most parties are of a leader type. Example: In such parties, the leader is treated as a director, as the "party head", and the political party as his private enterprise (Stanković, 2011).

- Decisions are made at the party's Main Committee, often by acclamation at the proposal of the party president, without any opportunity for intra-party discussion.

- The central bodies of the parties shall be elected on the proposal of and from the associates of the party leader.

- post-election fraud. Example: Pre-election promises after the elections are often turned into their opposite (Fund, 2013).

- Party discipline is implemented through the parliamentary caucus, in which no debate takes place among the deputies. Therefore, the head of the parliamentary caucus implements the will of the party leadership, disciplines the people's representatives, and imposes on them the will of the party leadership.

- Clientelist dependence of party personnel, policy decision-makers, against economic and financial elites (Orlović, 2008). Example: Party deputies make verbal promises to the financial elite that they will represent their interests and launch legislative initiatives on behalf of wealthy entrepreneurs. This causes immediate or direct interference of financial oligarchs in political and party life in the Republic, thereby strengthening their economic positions in society (Djurković, 2010).

- Spillage of money from public companies through employees ‒ party officers into party funds- Example: The misuse of party monopolies in the policy of public enterprises through the feigning deals of public enterprises with private agencies and companies owned by persons from the environment of holders of public and political functions in the country, resulting in taxpayers' funds being deposited to the accounts of party officials (Antonić, 2010).

Economic corruption

The most common forms of economic corruption in Serbia are the following:

- Entrepreneurs and owners of capital are not liable for business actions with their personal property, but companies are registered as "limited liability companies" d.o.o. Examples and consequences of this form of institutionalization of corrupt actions are: irresponsible business, bankruptcy, dismissal of workers, wild forms of privatization...

- “Political parties are the main actors that are capturing various state resources, distributing them either to business elites, or to their own electorate in exchange for different kinds of support.” (Cvejić, 2016: 247)

- Individual civil services (higher education institutions, agencies, etc.) independently determine the amount of employees' income (usurpatio Res publicae). Example: These services charge separately certain services (fees, taxes, etc.) as if they are on the market, although they are engaged in public activity, and instead of transferring funds to the budget, they have their fiscal cash from which they pay bonuses to employees.

- Directors of public enterprises are positioned according to political suitability. They are appointed by the government. Example: There are no public open competitions (Vesić, 2013).

- During the privatization process, the new owners raised loans from banks and placed the companies they bought under the mortgage. Example: thus, without any single euro, they bought the companies, took movable property from the purchased company (machines, materials, raw materials ...), which often exceeded the value of the company itself, and then only left the company to bank creditors.

- Similar is the situation when buying a company in attractive locations. Example: Ruined factory plants from the narrow and wide center of Belgrade, and other major cities in Serbia, were bought at bargain prices. Subsequently, the plants were demolished, and attractive locations were resold to foreign consortiums for the construction of residential and commercial buildings.

- Imprecise rules for obtaining the right to subsidies. For example, subsidies are distributed arbitrarily: 1) based on agricultural loans or grants; 2) based on grants or loans for finding a first job; 3) housing loans (for so-called "young couples"), etc.

- Imprecise specification regarding public procurement. The regulations can often be avoided because it is difficult to determine the criteria (e.g. qualitative condition versus quantitative). Then, a narrow specification that prevents public bidding is possible (e.g. in such cases there is only one bidder or service provider) (Borović & Tanascuk, 2004).

- Conflicts of interest which are very common. So, for example, officials do not give up management in companies owned by them, receiving gifts, non-transfer of management rights to "third parties" and performing a director's function in a private company while performing public office.

- Investor corruption: civil servants, by abusing their official position, divert budget funds by transferring money from the budget through so-called legal procedures through projects abroad. The same way is carried out "legalization of dirty money", which in this way loses all trace. Example: The money is returned from foreign accounts and pumped into companies in businesses that bring in lucrative profits. In this way, money is laundered (Milosavljević & Krstić, 2018).

Legal corruption

With regards to legal corruption, we can point to the following manifestations:

- Laxative application of legal regulations. Example: Legal provisions are interpreted as broadly as possible to preclude the specification of the rules and its rigorous application (Stanković, 2018).

- They apply so-called "rubber rules", interrelated interpretations that seek the meaning and spirit of the law, rather than adhering to the "letter of the law".

- Finding the so-called "legal gaps". Example: so-called "weak points" are found in general acts that make certain actions permissible, although according to the outcome of legal analogy they must be treated as impermissible (Perić-Diligenski, 2018).

- Frequent application of the so-called "targeted interpretation" instead of literal implementation of the law.

- Unequal conditions for everyone. Example: legal actions and procedures that privilege or favor certain categories of the population are being upgraded.

- Uncertainty of norms and other rules. Example: short lifespan of key legal norms.

- Non-existence of the right to appeal in certain cases, or a complex possibility of legal remedies.

- Introduction into the legal practice of the so-called "Impossible and unfeasible conditions" or "conditions that depend on others" to prevent competitiveness.

- Simplification of legal procedures that enable legal decision-making on the merits.

- Uncoordinated legal system: unclear rules, restrictive and exclusive norms that additionally create legal insecurity and impede legal and social traffic in one society (Milosević & Milašinović & Kešetović, 2010).

- Transferring decisions from the institutional-legal to the political level (Novaković, 2002). Example: abolition of legal procedures, (mis)use of so-called "vague legal norms".

- Legal arbitrariness.

Social corruption

The most common forms of social corruption in Serbia are:

- Major political decisions flatter the opinion of the least dynamic social layers on the bottom of the social scale. This is a classic example of populism. In this way, the legitimization of political decisions is realized, which meet minimum democratic standards.

- Various forms of discount and eligibility for privileged social groups.

- The rich have a special place: when it comes to taking from the budget of the richer, but also when it comes to the privileges of wealthier social groups and layers of the population. This taking from the budget often occurs ad hoc and is the result of the arbitrary action of political authorities.

- At one point, corruption is becoming so massive that it acquires the characteristics of a pandemic of wide proportions, so in the findings of the state the corruption is defined as "a way of life or a way of living".

- Erosive institutions create "systemic corruption", and it becomes a social category.

- In practice, clientelism forms parallel power structures and is a de facto source of power that undermines the institutions of the system. (Stanković & Perić Diligenski, 2023: 241).

- “Clientelism became the framework through which public resources could be converted into private capital for the purpose of reproducing and reconstructing the political elite.” (Babović & Cvejić, 2016, 15).

Measures to Strengthen Institutions and Weaken Corrupt Practices

Based on the stated above, certain measures may be offered to reduce corrupt behavior to a tolerable extent by removing institutionalized forms of corruptive activity:

1. Introduction of strict procedures for employment in public tenders.

2. The abolition of particratic rule: democratization of political parties by eliminating leadership parties. Strict control over the financing of political parties, strict sanctioning of the purchase of party and political functions, the prohibition of party employment and party racketeering of employees.

3. Only in exceptional cases allow the registration of limited liability companies (d.o.o. – Ltd.). Entrepreneurs in business must respond with their entire property.

4. Prohibition of public services and institutions to charge their services (except in exceptional cases). All funds collected from such transactions to be forwarded to the budget of the Republic. Banning public institutions to operate on domestic and international markets. The digitalization of public administration solves this issue.

5. In the privatization procedures, provide for a contractual compulsory investment clause in the development of a purchased company, which would prevent the full right to dispose of assets until a certain time period in which the business of the purchased entity becomes sustainable.

6. Precise the rule for obtaining the right to subsidies.

7. Total prohibition of conflict of interest. (A Commission for the Prevention of Conflict of Interest to which all officials must submit asset declarations before and after the end of their mandate. Such an institution already exists in some neighboring countries (e.g. the Republic of Croatia).

8. Adoption of a law with a compulsory public debate, and procedures that would make the legal solutions better and less contradictory.

Weak institutions – high corruption

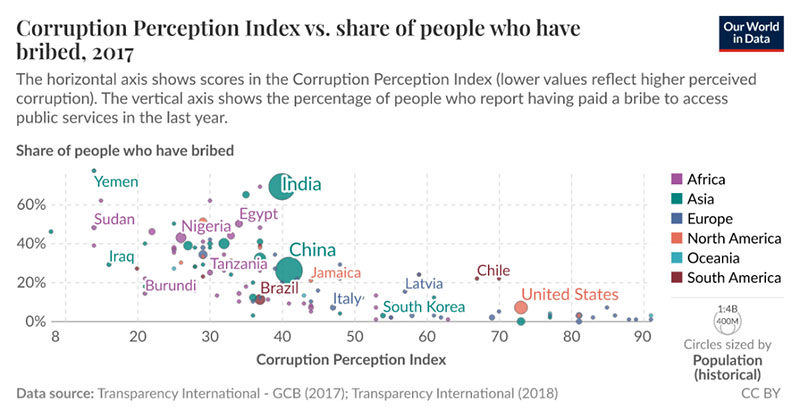

Weak institutions in a society are the main generator of corruptive activity. Corruption starts with representatives of the public authorities, that is, those persons who: are entrusted with certain functions, given public powers and management resources. Abuse of the entrusted function, public authority and resources to obtain personal tangible or intangible benefits is an essential definition of corruption (Heidenheimer & Johnston, 2002). It is therefore very important to emphasize the cause-effect link between institutional protection and corruption. It has been successfully confirmed in many political, sociological, legal and economic research so far, see the diagram below (Ortiz-Ospina & Roser, 2017).

Figure 1. Mutual correlation between public responsibility or strength of institutions on the one hand and bribery on the other.

Serbia is one of the countries where endemic events are characteristic of a large part of transition societies in Eastern Europe and the Western Balkans. Here we will list only the most important findings of the situation that refer to that: how weak institutions generate the phenomenon, growth and development of corruption in society, but also how unhindered corruption, and the established relationships of behavior and social activity further weak the already weak institutions. Thus, we arrive at the conclusion that weak institutions are unable to resist pathogenic and anomalous states (Djurić, 2009). Institutions turn into "shells", naked forms, in addition to which social traffic flows in parallel and smoothly, excluding institutional behavior and legal sanctions (Zindović & Stanković, 2012).

Insights into the state provide the following phenomena:

1. Simulated representative democracy. Democratic decision-making is in the service of respecting bare form. Strict control of candidates in terms of participation in elections for all levels of government. The selection is carried out within party structures, where there are several "party control filters" from the municipal committees of the party to the assessment of the suitability of a candidate expressed by a party leader. Control is also carried out through the financing of party activities. The misuse of financing political activities, or the self-financing of political activities, is an introduction to political corruption, in the following ways:

- Financing of campaigns of political parties;

- Corrupt flows of money from the economy towards politicians;

- Buying votes before and during the election campaign, as well as on election day.

2. Buying votes is done according to a pre-established scenario. Some votes are obtained through so-called "safe voting", where a voter is recruited to vote for a particular party, and in return is asked for proof that they voted as promised. Other votes are secured by making non-binding promises that something will be done or provided. Third voices are provided on the day of elections through the so-called "Bulgarian train": when a voter takes an already used ballot, puts it in a box and hides his own paper at the polling station, and then submits it as proof that the ballot was in the ballot box. The completed ballot is inserted into the ballot box, and a blank ballot is returned to prove that the completed ballot ended up in the box. In some cases, the state-of-the-art moving technologies of communication systems are also used to demonstrate loyalty to a particular political nomenclature. Thus, behind the screen, a mobile phone photographs a ballot paper and thus proves the expected choice of the respective voter.

3. Inadequate public procedures for financing the work of political parties result in the creation of non-institutional centers of power, which unconstitutionally and unlawfully define public sector work. So, for example, even the Supreme Auditor in the fight against corruption does not show the desirable effectiveness.

4. Democracy serves only as a screen for the legitimization of established "national" representatives. The appointed representatives work on:

- The takeover and total control of state institutions (which should remain independent);

- Protecting and expanding the established interest links of informal social groups (which have concentrated money and power in their hands);

- Privatization of state resources, and;

- Finally, legitimizing the existing situation in the international community. Legitimizing the existing corruptive phenomena, the appointed representatives of the peoples in the last instance bring in connection with regional stability, and this issue turns into a security issue of international importance. In a marvelous way, circles sunk deep in corruption present themselves and offer to foreign power centers as factors of regional stability and co-operation. Ultimately, these circles become the target of foreign stakeholders who give them certain roles in the new security system of regional stability. This creates a parallel system at the regional level, which has the role of strengthening the regional security system of non-institutional cooperation. (Lukić, 2014). The completed ballot is inserted into the ballot box, and a blank ballot is returned to prove that the completed ballot ended up in the box.The money from their jobs, illegally acquired, is now becoming an instrument of cooperation, and the interests they make are transformed into a factor in the stabilization of relations among the countries of Southeastern Europe and the Western Balkans.

5. Harmonization of regulations of transnational and international organizations, which often additionally encourage legal insecurity and weak national institutions for integration flows, are causing some of the most dangerous forms of corruption. Authorities and circles closely related to them can use this interregnum to channel new forms of corruptive action.

6. High-corruption hot spots most often come from the leadership of political parties, and then spread to the executive power, that is, the law-enforcers, or to judges who are law-abiding in a particular case. The bearers of the executive power, just like the judges, are unable to resist the pressure of political structures: they become targets of blackmail and, in the most significant cases, unanimously adjudicate.

7. A special form of "masked" corruptive activity lies in the mechanism of "silence of the administration", when certain organs of the executive power do not undertake acts from their scope, transferring responsibility to the competence of related institutions. This is a rather widespread phenomenon in which an executive institution is declared incompetent for a specific enforcement action. The person appealing for help encounters the "silence of the administration", the transfer of responsibility to other services, and so often the desperate applicant "spins in the circle” and does not encounter the necessary protection or service.

8. Regulatory bodies entrusted with the role of the fight against corruption are ineffective because the mechanisms of their actions are neutralized and pacified by power centers that disapprove the fight against corruption (Milosavljević & Krstic, 2012). Employees in regulatory bodies are, on the one hand, lured by privileges (high salaries, social status, etc.), but on the other hand they do not encounter cooperation and assistance from the executive and judicial branches of government. In this way, they are discouraged to take actions on positions they took over. In addition, they demonstrate in their actions the dependence on the influence of the political nomenclature and parts of the executive power.

9. In the economy, corruption is mostly expressed through the collapse of competition in the market (Djekić, 2009). Inequalities in business prevail. Indirect forms of bribery were developed, which do not fall under criminal incrimination. Selective application of the law. Further tightening of the business conditions, to consolidate the monopoly position. Legal uncertainty. Frequent change of regulations, and frequent change of rules. Legal incompleteness. Wide application of stretching norms. Merit assessment of legal provisions and legal status. Abuse of power and position in the procedure of providing "protection" to the employer, so that the businessman can continue to do business in a smooth manner. The legal system is used to eliminate the "excess of competition" on the market, to eliminate entrepreneurs from the market, and their capital "to be sucked" by the administration or stronger competitors in the market. This creates an environment in which "disloyal competition" prevails in the market.

10. Market corruption is most often recognized using personal acquaintances, influence and connections for the sake of suppression of competitive offers, thus creating a monopoly in a particular branch of the economy. A common phenomenon is a link between the politics and economy, where various feign jobs provide market earnings that are later divided among people from (political) government and businessmen. In this way, the government gets its businessmen, and the employers have their protectors in power. The owners of repressive instruments, without work, knowledge and accumulated capital, collect the rent for the performed counter-service.

A wide field of corruptive activity exists especially in the process of public procurement. Here corruption is particularly evident in the selection of bidders, incompetence and non-awareness of the members of the Commission for the selection of bidders, the influence of holders of public office in the procedure for the selection of bidders (Milosavljević, 2011).

Suggested measures to improve the situation in Serbia

Certainly, insight into the institutional state of affairs and the form of corruptive action remains unclear if some measures are not offered for overcoming the existing one. Among the most important measures it would be necessary to apply the following:

1. Effective application of anti-corruption regulations.

2. Anti-corruption prevention - removing any possibility of corruption.

3. Raising awareness and informing the public for public support for the implementation of the anti-corruption strategy.

4. The legal processing of all forms of "masked incriminations" that take place under the guise of corruptive behavior and action.

5. The removal of immunity from the highest political representatives of the authorities for whom there is obvious evidence that they have committed criminal offenses.

6. Confiscation of property from persons who are proven to have acquired profit through corrupt activity based on actions and procedures by which they violated legal provisions.

7. Disassembly of the "system of officers" who: implement the existing personnel policy, protect existing power relations and established relationships / interests, and prevent the social mobility and competitiveness of the elite.

Conclusion

Serbia was unprepared for the transition of the system from socialism to capitalism. Orthodox heritage of personal relationships, which had a rigorous system of punishment for corruption so characteristic of the period of real socialism, was destroyed by the withdrawal of the state from many public spheres of life and by deregulation in the transition period. This created a legal chaos and social anomie. The resulting legal gaps have become El Dorado for various forms of machinations: from small bribes to corruptive actions of systemic proportions.

This paper has managed to prove the correlation between the weak institutions of the state and the high level of corruption. This process is dialectical, so the author have established feedback: showing and proving that corruption weakens the already fragile institutions of the system, and how it destroys the system as a whole.

Therefore, the author propose a set of measures to remove institutional weaknesses that lead to the emergence, growth, spurring and development of corruption.

Literature:

1. Antonić, S. (2010). Network of school friends in the political elite of Serbia. National Interest 9, N°3 (2010): 329-350. Belgrade: Institute for Political Studies.

2. Babović, M., Cvejić, S. (2016). Briefing on Party Patronage and Clientelism in Serbia. Université de Fribourg.

3. Borović, S., Tanascuk, N. (2004). Automated decision support system in public procurement processes. Military Technical Gazette 52, N°1 (2004): 9-25. Belgrade: Ministry of Defense of Serbia and Montenegro.

4. Breen, M., Gillenders, R. (2012). “Corruption, institutions and regulation”. Economics of Governance. Vol. 13: 263-285. Springer Science+Business Media.

5. Cvejić, S. (2016). “On Inevitability of Political Clientelism in Contemporary Serbia”. Sociologija. Vol. 58. № 2: 239-252. Belgrade: Sociološko naučno društvo Srbije.

6. Fund, J. (2013). Stealing Elections ‒ How Voter Fraud Threatens Our Democracy. New York City: Encounter Books, 2013.

7. Heidenheimer, A., Johnston, M. (2002). Political Corruption – Concepts and Context, New Brunswick/London: Transactions Publishers, 2002.

8. Djekić, I. (2009). Competition policy in Serbia – situation and perspectives. Economic Themes 47, N°2 (2009): 229-240. Nis: Faculty of Economics.

9. Djuric, A. (2009). Corruption in Serbia, Economy 55 (2009): 54-69. Nis: The Association of Economists Niš, 2009.

10. Djurković, M. (2010). Transition without transformation – or how the elite emerged from the nomenclature in Serbia. National Interest 9, N°3 (2010): 307-328. Belgrade: Institute for Political Studies, 2010.

11. Krstić, J., Milosavljević, Z. (2017). “Serbian laundromat”. Revista Direitos Humanos Fundamentais. Vol. 17. № 2: 173-184. Osasco SP: Editora do Centro Universitário FIEO, San Paolo.

12. Linz J., Stepan, A. (1996). Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation –Southern Europe, South America, and Post-Communist Europe. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

13. Lukić, G. (2014). The significance of the regional initiatives of Southeast Europe in the fight against organized crime. Security, N°1 (2014): 175-192. Belgrade: Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Republic of Serbia.

14. Milosavljević, Z. (2011). “Inappropriate enrichment and corruption in Serbia”. Political Review 30. № 4: 173-198. Belgrade: Institute for Political Studies.

15. Milosavljević Z., Krstic, J. (2012). Institutional mechanisms to control the financing of political activities in the party system. Military Paper 64, N°3 (2012): 116-129. Belgrade: Ministry of Defense of Republic of Serbia.

16. Milošević, G., Milašinovic, S., Kešetović, Ž. (2010). „Corruption in Serbia“. Collection of works Methodology for building a system of integrity in institutions on the fight against corruption: 161-180. Banja Luka, 2010.

17. Novaković, N. (2002). “Corruption in Serbia”. Sociological Review 36, № 1-2 (2002): 227-239, Belgrade: Serbian Sociological Association.

18. Orlović, S. 2008. Serbian Political Life –from Democracy to Particracy. Belgrade: Official Gazette, 2008.

19. Ortiz-Ospina, E., Roser, M. (2017). „Corruption“, How common is corruption? What impact does it have? And what can be done to reduce it? Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/corruption

20. Perić-Diligenski, T. (2018). “Corruption in Serbian political culture”. Collection of works: Identity, political culture, institutions, (edited by Vladan Stanković) Book 7: 101-118. Belgrade: Institute for Political Studies.

21. Stanković, V., Perić Diligenski, T. (2023). “Informal Forms of Social Anomy”. Serbian political Thought. Vol. 80. № 2: 227-249. Belgrade: Institute for Political Studies.

22. Stanković, V. (2018). “Serbian identity, political culture and attitude towards institutions”. Collection of works: Identity, political culture, institutions, (edited by Vladan Stankovic). Book 7: 119-140. Belgrade: Institute for Political Studies.

23. Stanković, V. (2011). Political elites in Serbia – from particracy to plutocracy. Political review 28, № 2: 93-108. Belgrade: Institute for Political Studies, 2011.

24. Sherman, P. (1980). “The Meaning of Nepotism”. The American Naturalist. Vol. 116, №: 604-606. Chicago: The University of Chicago.

25. Van Duyne, P., et al., (2010), “Searching for Corruption in Serbia”, Journal of Financial Crime, Vol. 17. № 1: 22-46. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

26. Vesić, M. (2013). “Departisation is more than non-party directors”. Transparency in the operation of public enterprises – research on the publicity of work of the state-owned company. Belgrade: Open Society Foundations, 2013.

27. Zindović, I., Stanković, V. (2012). “Legalized forms of corruption in Serbia – anomalous states of social entropy”. Sociological Review. Vol. 46, № 1: 17-34. Belgrade: Serbian Sociological Association.

Cite this article

APA 6th Edition

Milosavljević, Z. (2025). Transition in Serbia: Institutions and Corruption. National Security and the Future, 26 (1), 159-178. Preuzeto s https://hrcak.srce.hr/331826

MLA 8th Edition

Milosavljević, Zoran. "Transition in Serbia: Institutions and Corruption." National Security and the Future, vol. 26, br. 1, 2025, str. 159-178. https://hrcak.srce.hr/331826. Citirano DD.MM.YYYY

Chicago 17th Edition

Milosavljević, Zoran. "Transition in Serbia: Institutions and Corruption." National Security and the Future 26, br. 1 (2025): 159-178. https://hrcak.srce.hr/331826

Harvard

Milosavljević, Z. (2025). 'Transition in Serbia: Institutions and Corruption', National Security and the Future, 26(1), str. 159-178. Preuzeto s: https://hrcak.srce.hr/331826 (Datum pristupa: DD.MM.YYYY)

Vancouver

Milosavljević Z. Transition in Serbia: Institutions and Corruption. National Security and the Future [Internet]. 2025 [pristupljeno DD.MM.YYYY];26(1):159-178. Dostupno na: https://hrcak.srce.hr/331826

IEEE

Z. Milosavljević, "Transition in Serbia: Institutions and Corruption", National Security and the Future, vol.26, br. 1, str. 159-178, 2025. [Online]. Dostupno na: https://hrcak.srce.hr/331826. [Citirano: DD.MM.YYYY]