Abstract: The amount and promptness of data associated with instant communication applications has completely reshaped the information environment. External malign actors who seek to exert their influence on public opinion no longer need to dispose illegal radio stations and secret distribution of literature; it is enough to have Telegram. The Telegram application represents a significant vector of Russian influence in the Western Balkans. The application dominantly operates in nine languages. With its technical characteristics, it represents a medium between a social network and a space-communication application.

Telegram does not have technical solutions that would protect users from dangerous and fake content as Facebook and Twitter do. After the Russian aggression against Ukraine, Telegram became a basic tool for distributing viral videos of armed conflicts, but also a tool for information shaping.

The phenomenon of Telegram influencers further complicates protection against informational influence operations. Through interaction, these influencers build a relationship with an audience that does not have the capacity to verify the large number of claims which are made nor their veracity. The consequence of influence operations through Telegram leads to the creation of the ideological engine model. Over time, the public adopts the disputed narrative as its own rational tool for interpreting contemporary international relations and the nature of Russian aggression. Telegram's technical solutions make it suitable for conducting influence operations. Sufficiently sophisticated users can skillfully hide their identity. On the other hand, users who do not hide their identity and represent the bearers of Russian propaganda are not obstructed in propagating harmful content. In this paper, we tried to look at the characteristics of information operations through the Telegram application.

Keywords: Telegram, Influence operations, hybrid warfare

Introduction

Influence operations are constant activity in geopolitical competition. Nature of influence operation differs in accordance of strategic goals of involved actors. Impact of influence operations is not same in peace and war time. After aggression on Ukraine by Russia impact of Russian influence operations are more destructive and dangers. Russia war propaganda deploying disinformation, information shaping and manipulations for global audience consumption. Main lines of that propaganda are internal disruption of EU countries in struggle to motivate citizens for anti-aid campaigns. Iin other words creation of pressure for quitting support for Ukraine. After semi successful counter measures against Russian propaganda channels now is more visible usage of opinion makers or influencers.

In this article we are analyzing one specific playground of influence operation: a Telegram application. In Serbian information environment a Telegram application is not a main vector of Russian propaganda, perforce it is supplement channel. Telegram has well developed audience in Serbia, so it can very easily become mainstream axis. Opinion makers are always specific oriented by exact country, history background, mentality and common prejudices, which means that opinion makers on telegram are real social network influencers. If they are influencers that means cultivating audience trust, reliability with capability to invoke actions by their audience.

Telegram application cannot be ignored. Its impact has to be evaluated and estimated on basis of technical, law and security aspects. Telegram groups and channels, in case of Russian propaganda, are environment for radicalization and extremism which must be treated as national security threat.

In this paper, we base the hypothesis on the Telegram application as a unique information environment that remains beyond the reach of regulatory oversight and adequate analysis of the content that is marketed in the information ecosystem. Through this paper, we will identify the reasons why Telegram channels are conducive to information operations. Through information operations, political decision-making is influenced; divisions and inter-ethnic tensions as well as social subversions are created. Influence operations can lead to violent extremism and can represent a form of threat to democratic societies.

Information operations in Serbia - a brief review

Influence operations as a form of endangering national security are considered interference in the internal affairs of a sovereign state. These operations can be public, semi-public and covert. Authoritarian regimes continuously seek to undermine trust in democratic institutions and processes. These influences, depending on the degree of national resilience and the development of democracy, it can be marginal and dominant social discourses. Russian aggression against Ukraine has created a completely new state of security architecture in Europe. The unprecedented aggression has brought to the fore questions of the resilience of democratic societies to malignant influences that seek to reshape public opinion and decision-making.

In the past 100 years, the Western Balkans has been a zone of strategic interest for the Russian projection of power in South-Eastern Europe. Inter-ethnic disputes, the unresolved status of Kosovo, the presence of nationalist rhetoric objectively favor the performance of Russian activities in this region. Much has been written about the malignant Russian influence, the literature agrees on the consequences of that influence. So far, no publicly available analysis has been published regarding the financing of Russian influence operations in Serbia and the Western Balkans. There are publicly available reportages and reports on individuals and organizations linked to the recruitment of persons for the Russian armed forces, reports on contacts of political parties and organizations. These groups can be classified as pressure groups in the moment when they take part in propaganda activities. If we continue with the content analysis regarding the actions of pro-Russian entities, we come to a specific group of opinion makers. For easier understanding, we can divide this group into individuals and organizations. The goals of this group can be limited to the creation of an information-ideological base in favor of the Russian geopolitical projection.

The worrying fact, which can be considered as a challenge for the national security of Serbia, refers to the activities of scientific institutes founded by the Republic of Serbia in creating a favorable ideological and informational setting that corresponds to the interests of Russia. By law, these institutes are autonomous from the state. Through this channel, a scientific alibi is created for the correctness of Russian war aims and the Russian vision of international relations. These phenomena would represent isolated cases and lines of work; however, due to the lack of media literacy, all of the above represents a single pro-Russian united front.

The phenomenon of influence operations on social networks, including chat applications such as Telegram, represent a separate training ground for performing information operations. In contrast to the media appearances of opinion makers, the activities of scientific and other organizations, cyberspace has the advantage of anonymity and absence of responsibility. In this paper, we want to look at the use of Telegram as a unique channel for conducting Russian influence operations. We believe that it is necessary to look at the role of the Telegram application as a channel through which it is possible to carry out information operations, radicalization, violent extremism and recruitment.

Information operations in light of Russia's aggression against Ukraine

The Russian aggression against Ukraine resulted in the process of the entire re-examination of the relations between Europe and Russia. The hybrid threats posed by Russia did not start on February 24, 2022, they already have their own stable continuity. For years, Russia has been using the whole playbook of information manipulation and interference, including disinformation, in an attempt to sow divisions in the societies, denigrates democratic processes and institutions and rally support for its imperialist policies. In European Union External Action report, we can find a conclusion that Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022 has shown, again, the wide spectrum of tactics, techniques and behavior (TTB’s) used in the information environment, while building mostly on well-known disinformation narratives (EEAS, 2023). Influence on public opinion as well as disruption of decision-making lie at the center of these activities. Information influence operations must be analyzed as a subgroup of hybrid threats. In no case can influence information operations be viewed as a separate activity outside of a wider context.

Hybrid threats are directly aimed at the national security of modern states. The paralysis of society, i.e. decision-makers in terms of sovereign decision-making, is fully reflected in the autonomy in decision-making. In addition to the fact that the hybrid threat does not have to be open and public in its manifestation, it can certainly achieve its goals from another plan. By creating a social environment that strongly opposes certain policies or foreign policy decisions, goals are achieved without the use of conventional forces. The danger of disinformation, fueled by global events, is directly reflected in the containment of the pandemic, and it affects the countries of the Western Balkans, whose media uncritically transmit Russian propaganda, which gives space to legitimate and true social discourse (Životić & Obradović 2021). The aggression against Ukraine shows us the logical sequence of activities in the absence of the achievement of goals through hybrid action. In this regard, hybrid threats can be considered a precursor to the use of other violent actions, such as assassinations and coups. The attempted coup d'état in Montenegro, as well as the organization of church protests in 2020, indicate that the path from disinformation and information influence operations sooner or later ends with the manifestation of open forms of endangering national security. The moment when it was not possible to prevent Ukraine's foreign policy orientation by occupying Crimea and part of eastern Ukraine, a new stage of open aggression followed.

National security in the context of human and national security can also be the psychological freedom of a country from the fear that the country will be unable to resist threats related to its survival and national values, which come from abroad or from the country itself (Kegley & Eugene, 2004). By looking at the definition of national security as freedom from fear, one can identify the objectives of Russia's hybrid threats. Energy blackmail and the threat of "freezing Europe" represent an excellent example of influencing the public opinion of European countries in order to prevent military and material support for Ukraine.

Thus, hybrid threats have specific and measurable objectives. Hybrid threat actors are rightly banking on their success. Hybrid action is a planned, organized, pre-prepared, coordinated, economical action of state actors against the civilian population, institutions and interests of sovereign states, with the integral use of the principles of military tactics and intelligence work, primarily subversive action with the ultimate goal of paralyzing society, the state system calculated in coercion in order to achieve certain concessions and the desired behavior of the state as a whole (Životić & Obradović, 2022). On the example of Russian influence operations as a sub-group of hybrid action, that effect is easily measurable on the example of Serbia. According to a public opinion survey, opposition to the introduction of sanctions against Russia amounts to over 70% of public opinion according to a 2023 survey conducted by NGO the New Third Way (Gočanin, 2023). If the objective facts regarding the Russian aggression against Ukraine are taken into account, we rightly state that we have a very precisely measured success of Russian propaganda.

Information influence operations

Information influence activities also known as cognitive influence activities, are activities conducted by foreign powers to influence the perceptions, behavior and decisions of target groups to the benefit of foreign powers. Information influence activities can be conducted as a single activity or as part of a larger information influence operation combining various and multiple activities (MBS, 2018). The distribution of information or disinformation in order to achieve the desired behavior has changed its methods throughout history, but not its original purpose. The digital environment has led to the fact that every citizen can access materials from the Ukrainian battlefield in real time. Social networks are flooded with content related to this conflict. In open source, it is possible to find footage of combat operations, photos of collapsed buildings, and killed people, but you can also find heaps of forgeries that were prepared in advance and planned to be aired.

Department of Homeland Security defines foreign influence operations as malign actions taken by foreign governments or foreign actors designed to sow discord, manipulate public discourse, bias the development of policy, or disrupt markets for the purpose of undermining the interests of the United States and its allies (DHS 2018). These operations seek to influence specific groups or the entire society. By their nature, they can be aimed at maintaining existing thought patterns or at establishing completely new thought patterns. Cognitive warfare is the weaponization of public opinion by an external entity, for the purpose of influencing public and/or governmental policy or for the purpose of destabilizing governmental actions and/or Institutions (Bernal et all 2021). By analyzing the content, the authors noticed an important difference between the application of Russian narratives in influence operations in Europe and Serbia. In Serbia, through information influence operations, efforts are being made to maintain the existing situation and conviction in public opinion, while in Europe, the goals are set initiate change of public opinion in mobilization action against the decisions of their governments. The legitimate question of the legality and legitimacy of information operations is raised, the key is at what point these activities become illegal. The nature of information operations can be defined in the following ways:

- Information influence activities are the illegitimate attempt to influence opinion-formation in liberal democracies (legitimacy);

- They are conducted to benefit foreign powers, whether state, non-state or proxies (intention);

- They are conducted in the context of peace, war and hybrid threat- or grey zone-situations, i.e. situations of tension that are neither peace nor war (ambiguity) (Pamment et al. 2018).

Propaganda and influence operations often overlap. Propaganda can be carried out with accurate information, disinformation and misinformation. Propaganda can be defined as the systematic dissemination of information, in a biased or misleading way, in order to promote a political cause or point of view (OED, 2011). By comparing the definitions of propaganda and influence operations, we see that the goals match and the methods differ. Influence operations represent a continuous and more sophisticated way of influencing society. The emergence of social networks, the Internet, and applications like Telegram have greatly expanded communication channels that overlap and transcend conventional barriers. The ban on RT and Sputnik represents a formal technical-legal measure to limit Russian war propaganda, while at the same time the Telegram application remains outside the scope of these restrictions. The fourth wave of propaganda is taking place, which unites the previous propaganda channels into a unique interactive audio-visual form provided by the Internet. A cyber influence operation can be defined as focused efforts to understand and engage key audiences in order to create, strengthen or preserve conditions favorable for advancing interests, policies, and objectives, through the use of coordinated programs, plans, themes, messages, and products (Larson et al 2009).

The use of information and/or disinformation can cause riots, demonstrations, passive opposition (attitude of Serbian citizens towards sanctions against Russia), radicalization and incitement of violent extremism. There are three categories in defining social influence: actors, interactions, and networks (Tayouri, 2020).

Analysis of Information Operations can be based on:

- Technical evidence, consisting of the observable traces that an adversary leaves behind at the level of digital signals;

- Behavioral evidence, supported by knowledge of the methods by which different adversaries carry out their work (this is often termed Tools, Techniques and Procedures or TTPs);

- Contextual evidence, which consists of an assessment of the content of IIO (Influence Information Operation), the socio-political context in which IIO takes place, and the motivations of the adversary;

- A legal & ethical assessment of whether assigning blame is proportionate, and whether it sets into motion considerations relating to e.g. political or commercial fallout, treaties or litigation (Pamment & Smith, 2022).

The line between the open dissemination of disinformation and the communication of official announcements often blurs the essence of the enumerated properties. There is no influence operation without the active participation of the bearer in way of coordinated cooperation in spreading those messages that aim to produce the desired effect. This type of interference in another country’s politics would require the target to be the public rather than politicians because, although politicians have power, civilians must approve of their representatives’ actions (Bernal et al. 2020). The very way of proving the existence of influence operations is based on the analysis of content and technical parameters. In particular, content analysis should be singled out as a key aspect of identifying the presence of an influence operation, which does not necessarily include the identification of the actual holders and their handlers. The evidence may be derived from three kinds of data:

- Open source (open-source information and intelligence, OSINT)

- Proprietary source (based on privileged backend data sources such as those available to digital platforms, private intelligence and cyber security companies)

- Classified source (based on secret information primarily held by governments and the military) (Pamment & Smith, 2022)

The combination of parameters of covert, influence, political, economic, judicial/law and informational, is what we can categorize as priming. The covert nature moves the activities away from acceptable and legitimate actions in international affairs (Bergaust & Sellevåg 2023). We are actually facing a dilemma, both academic and practical, in terms of the elements for legally proving the existence of influence operations. From the point of view of counterintelligence work, it is of crucial importance to document and prove the entire information/intelligence cycle in terms of the organizer and hander. The cycle of information operations includes cultivating “useful idiots” who believe and amplify the narratives, and encourage them to take positions even more extreme than they would otherwise (Schneier, 2019). Analyzing the content of the information environment in Serbia, we find that Russian tactics do not differ from the existing 4D approach. When it comes to defending Russia, different tactics are used. They can be summed up in four words: dismiss, distort, distract, and dismay (Nimmo, 2015).

Russian influence operations have the characteristic of a united front in Serbia. Without a detailed analysis, it is easy to see the existence of synchronized action in the spread of narratives from mainstream media, YouTube channels, social networks and Telegram. Synchronization, which includes spatiotemporal coordination in spreading a certain message, indicates the existence of a center from which the information operation is coordinated, therefore the pro-Russian mood is not a consequence of the natural state, we base this attitude on an inauthentic interpretation of certain Russian narratives in a certain period. The information cycle pattern is fairly easy to follow from week to week. The same verbal interpretations point to the existence of a prepared message box. In the literature, one can often find the coin cognitive war and information war. Perhaps a sharper delineation is that information warfare seeks to control pure information in all forms and cognitive warfare seeks to control how individuals and populations react to presented information (Megan, 1999). Cognitive Warfare is a strategy that focuses on altering how a target population thinks – and through that how it acts (Backes & Swab 2019).

The Western Balkans represent a strategic priority of the Russian Federation in terms of maintaining its influence, which is based on preventing Euro-Atlantic integration and maintaining inter-ethnic conflicts, then we must also take into account the definition of information warfare used by Russia. Information War is the confrontation between two or more states in the information environment with the purpose of inflicting damage to information systems, processes and resources, critical and other structures, undermining the political, economic and social systems, a massive psychological manipulation of the population to destabilize the state and society, as well as coercion of the state to take decisions for the benefit of the opposing force (Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation, 2011). Psychological manipulation is an integral part of Russian influence operations where the dichotomy of good and evil is constantly highlighted, where the West is highlighted as "evil" and "dangerous" and Russia as the protector of "traditional and Christian values". The victimological pattern of thinking further favors the success of the Russian approach based on confirmation bias in the target population. Russian social media disinformation campaigns can be viewed as a "disinformation chain," winding from Russian leadership, to Russian organs and proxies, through amplification channels such as social media platforms, and finally to consumers (Bodine-Baron et al. 2018).

What is Telegram and how is it different from social networks?

In order to gain insight into the Telegram application during this work, we got acquainted with the basic features offered by the creator and owner of the application. Detailed manufacturer specifications are available at www.telegram.org. The application itself was launched in 2013 and today has around one billion users. The statistics related to the application Telegram offer us the following overview, which refers to half a billion monthly active users, 55 million daily active users and the seventh-ranked application in the world by download (Dean, 2023). 310 million people downloaded the Telegram application in 2022 (Curry, 2023). With an insight into the technical characteristics of Telegram for the purposes of this work, we will present only those that can favor the execution of information influence operations, radicalization and calls to violent extremism. Telegram is a completely free application that is easily available through download services for Android, IOS, Harmony OS (Huawei), PC, Mac and Linux applications.

To register and create a user account, you need to have a phone number. The same user account on Telegram can be simultaneously active on a computer, tablet and phone. It is only important that it has a phone number during first registration of account. In case of changing mobile phone number, it is possible to keep the previously created user account. This opens up the possibility that users can change the original data they have left, that is, we cannot actually reliably know who is the owner of the account, whether it is the person who is the user of the phone number or someone else who uses the username.

The following explanation related to the phone number can be found on the official Telegram site if you will use the new number for a limited time (e.g., you're on a trip or vacation), there's no need to do anything. If you want to keep using both numbers (e.g., you have a work phone and personal phone), choose one as your Telegram number. You may create another Telegram account on the second number as well, for example, if you want to keep work and personal chats separated. It is possible to log in to one Telegram app with up to 3 different accounts at once . For the purposes of this work, we created a Telegram account and after installation we removed the phone card and deactivated the phone number, the Telegram account remained active. The absence of a phone number affects the security of the account itself in terms of opening an account on other devices and controlling the account itself, but not the ability to exchange messages and use Telegram.

What’s up application does not allow the use of the application without an active phone number in the mobile device. Unlike WhatsApp, Telegram is a cloud-based messenger with seamless sync. As a result, you can access your messages from several devices at once, including tablets and computers, and share an unlimited number of photos, videos and files (doc, zip, mp3, etc.) of up to 2 GB each . Communication on Telegram can take place as communication in form of user-user, group (multiple users interacting), channel (one user communicates with multiple followers). What is particularly interesting about Telegram refers to the possibility that each individual user can create an unlimited number of groups with a number of members that can be up to 200,000 members. A Telegram channel can have an unlimited number of members. Hypothetically, this means that one user can administer and control the distribution of (dis)information in several groups that can be specific according to user demographics, user geography, and user interest. Essentially one person can coordinate a large number of different groups without limitation. Telegram users can sign up with virtual numbers or foreign phone numbers that are unrelated to their true identities. Users can also register for the service via a one-time SMS service, with a one-time password (OTP) number given to the one-time SMS service rather than their private phone (Kela report 2023). On its website, Telegram states that it deliberately uses cloud services in different countries in order to complicate formal jurisdiction procedures. Cloud chat data is stored in multiple data centres around the globe that are controlled by different legal entities spread across different jurisdictions. The relevant decryption keys are split into parts and are never kept in the same place as the data they protect. As a result, several court orders from different jurisdictions are required to force us to give up any data .

If the user wants to avoid storage on Telegram's cloud, he can start the secret chat option in which only two users can have access to the content of the messages. In this case, users can communicate only through one device, regarding, secret chat as an option is linked to the device on which this option is activated. By deleting messages, videos and pictures by one user, the same content is automatically deleted for another. The content of the conversation can be pre-set to self-destruct mode. Telegram is undoubtedly a commercial application that lives on the amount of traffic of its users. It is about the fact that there is a Telegram Premium where the user can rent unlimited cloud storage, i.e. 4 GB for each document. Armed conflicts and war propaganda generate a large amount of material. Telegram, like any social network, maintains its audience through content creators. In the case of Telegram, the old saying is confirmed - if you don't know where the profit comes from, that profit is you.

Unlike Facebook and Twitter, Telegram does not have the option of identifying and sanctioning coordinated unauthentic behavior. At the same time, Telegram has very effective attributes of social networks such as content sharing, commenting and interaction with other users in a special digital environment. For conspiracy theorists, extremists and anti-social groups, it’s a perfect combination of secure enclave and public promotional platform allowing them to spread their beliefs, recruit supporters and plan future activities (Reeve, 2021). The EU code of practice on Disinformation implies the responsibility of the platforms for the content that is spread on them (EU Commission 2022). Apparently Telegram still resists legislation from the US to Europe regarding its operations. Telegram does not have any restrictions on the dissemination and promotion of disinformation and misinformation on its channels and groups. Indeed, the producers of misleading content may deliberately migrate to such places when they are removed from more mainstream platforms as a result of moderation decisions, thus fragmenting their presence online (Rogers, 2020). The subject of a special study should be the hypothesis of how much content from unregulated platforms like Telegram reaches other people.

Eu Disinfo Lab in its report entitled Disinformation on Telegram: Research and content moderation policies from December 2022 refers to two techniques for monitoring Telegram channels, i.e. via Google Custom Engine service and Telegram API. In the direction of Telegram API one of the main advantages is that it allows monitoring relevant chats and acquiring information periodically without requiring any active user interaction (e.g., by using cronjobs) or, as soon as new information pops out, in a fully automated manner (EU DisnfoLab, 2022).

Telegram and Russian propaganda in Serbia

It is worth emphasizing that Telegram channels are as publicly accessible as many social media platforms are, in that you simply need to register a username in order to join channels and engage with the material or users (Puyosa, 2023). Telegram, as a specific digital ecosystem, functions as a social network with more "trust" in its philosophy. This trust users base on the belief that they cannot be easily detected for offenses such as threats to life, racism, insults and other threats, which are relatively effectively sanctioned on other social networks and messaging platforms. In such an environment, the risk of radicalization and violent extremism increases further.

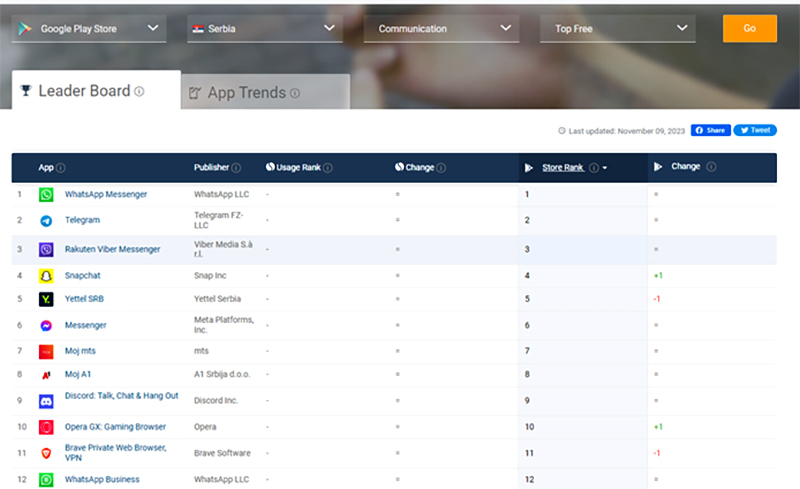

Telegram is the second most popular application in Serbia. This application has become one of the main carriers of Russian war propaganda and disinformation in Serbia.

Figure 1. Popularity of communication applications in Serbia Source: Similarweb.com

The vast majority of the channels in the network cross-post identical messages in multiple languages, indicating that they do not target foreign audiences with tailored messages (Gigitashvili, 2023). An identical conclusion can be made in the case of pro-Russian Telegram channels in the Serbian language. For reasons of preventing popularity, the authors in this paper will not list individual pro-Russian channels that are active in the Serbian-speaking area. It should be borne in mind that the main carriers of Russian propaganda on Telegram use both groups and channels. The most popular propaganda channels have about 100,000 followers and an average of thirty thousand views per post, the number of reactions per post varies between 600 and 1000. A trend of copy-paste content from pro-Russian Telegram channels to other social networks such as Twitter and Facebook have been observed. Those copy-paste activity in some cases are not sourced, so the users will not be notified that source is propaganda Telegram channel. The total number of users of the Telegram application in Serbia is not available, nor is the number of active users known. The 10 most prominent pro-Russian channels likely have a large overlap in terms of their audience. For the purpose of comparison, Twitter has 605 000 users in Serbia. What characterizes those Telegram channels is the existence of influencers, who are most often either propagandists with the role of journalists, or foreign fighters/terrorists whose presence in Russian formations is illegal from the aspect of the law of the Republic of Serbia. Another ‘shortcut’ for truth might involve defaulting to one’s own personal views (Ecker, U.K.H., Lewandowsky, S., Cook, J. et al. 2022). These influencers build a relationship with their audience, introduce elements of personal truth and virally which favours transmit of the desired message box assigned to them by their Russian handlers. When deciding what is true, people are often biased to believe in the validity of information (Pantazi, M., Kissine, M. & Klein, O. 2018).

Data from DFRLab indicate that Russian propaganda activity has a high level of coordination. In the list of channels that serve as a form of recruitment for the digital propaganda war, there is also a channel in the Serbian language, InforDefSerbia (DFRLab 2023).

By analyzing the content in the scientific work Spreading Russian Propaganda in the Western Balkans - Case Study Serbia, the authors identified a high level of logistics in terms of translating and editing content for use in the Serbian information environment (CZSA,2022). With the use of Telegram influencers, Russian propaganda influences the construction of reliable and exclusive sources that the recipients of information perceive as credible. Moreover, people often overlook, ignore, forget or confuse cues about the source of information (Mitchell, K. J. & Johnson, M. K. 2009). Telegram's technical capabilities enabled rapid exchange and a large amount of misinformation that the average user is unable to verify due to subjective and objective circumstances. Individuals may be discouraged from activities that would lead to the formation of true beliefs not because they fear that deception is unavoidable, but instead because they recognize that, in an information environment populated by fakes, reliable inquiry is likely to be time-consuming (Harris, 2022). Instead, the Telegram audience serves as an amplifier of disinformation that further spreads them in their social and online circles.

Figure 2. List of Russian Telegram channels created with same purpose for different countries

Video materials shared by certain pro-Russian Telegram channels can also be seen on television, where it is clearly indicated from which channel the video material was taken. In this way, the channel that spreads disinformation directly gains legitimacy in the public eye. Needless to say, these Telegram channels are not copyright owners, but only sharers of other people's video content. Online strategies to this shift to EMAs by establishing Russian state-sponsored channels that blast propaganda and disinformation, which they frame as “leaked information” to appear trustworthy (Trauthig, 2022). Telegram communities are far more vulnerable to misinformation because they are in a pattern of confirmation bias. In many surveys that dealt with the motivation and reasons for switching to other platforms, distrust in mainstream sources is one of the dominant motives. Mistrust and a conspiracy view of the world make users more vulnerable to disinformation.

Pro-Russian Telegram channels in the Serbian information environment do not limit their participation only to Russian war propaganda regarding the events in Ukraine. These channels represent a completely autonomous channel for carrying out information operations of influence in terms of spreading anti-Western propaganda, promoting the Russian and Chinese geopolitical narrative, they take part in internal politics and social processes, they spread inter-ethnic and inter-religious hatred, they are particularly active in marketing content that opposes the normalization of relations between Serbia and Kosovo. Coordinated efforts of pro-Russian Telegram channels were identified during the crises connected with Kosovo dispute. The same pro-Russian war propaganda channels, both Russian and Serbian, started to spread same pictures and messages on both languages as it was identified in Radio Free Europe research (Živanović & Kovačević,2022).

Proxies that manage propaganda channels and groups represent a key link in the whole method. We strongly believe that the performance of this information channel would be much weaker in the absence of personification. People who run Telegram channels and groups are also indoctrinators and opinion makers who manage the information shaping process. The information-shaping method refers to the methodological unity and tactics applied by Sputnik and RT.

Telegram and radicalization

In November 2022, the European Parliament proposed to the European Commission that the Russian paramilitary formations Wagner and other paramilitary units be added to the list of terrorist groups, one of which is known as the Kadyrovs because its members are financed, trained and publicly supported by the leader of the Chechen Republic, R. Kadyrov (Kešmer, 2022). This was immediately followed by a large number of obviously orchestrated and pre-prepared posts on numerous Telegram channels promoting Russian policy and military aggression towards Ukraine. The pamphlets contained insulting comments against the EU on the one hand and on the other called for even fiercer attacks on targets in Ukraine. If we look at numerous reports on propaganda and the spread of fake news under the sponsorship of those who promote and represent the interests of the Kremlin on Telegram, as well as the number of visits to such Telegram groups, we can conclude that this platform is not only a current weapon in the hands of them, but also that its popularity warns those circles of what awaits us in the near future with the Metaverse. Because if Telegram as a simple platform is so effective in terms of radicalization, the question arises as to what impact Metaverse will have as a kind of super world of 3D virtual worlds in which victims of radicalization will be able to communicate directly through VR equipment with some of the members of the Russian paramilitary units, HAMAS, ISIS, Al Qaeda.

In the Metaverse, thanks to VR technology, victims of radicalization will be able to be in the same room with terrorists and war criminals, which will make the effect of radicalization faster and stronger thanks to the intimacy achieved. This is supported by research in Great Britain, which states that the most radicalized are those people who have suffered the influence of online platforms and the so-called offline radicalization, i.e. they had the opportunity to see and listen to live preachers in addition to online influence (Kenyon, 2021).

The best indicator of how technology is ahead of its time, and thus the legal regulations, is that the EU Agenda for the fight against Terrorism from 2020 and its regulation 2021/784 on the fight against the spread of terrorist content on the Internet recognize and emphasize the dangers of radicalization on the Internet, but they do not define the concept of online radicalization (EU Commission, 2020). Unfortunately, this is proof of the administration's slowness, because by the time the decision-makers agree on a harmonized definition of online radicalization, terrorists will already have not only a ready answer, but probably several new solutions to continue their online activities. In the absence of a definition from Brussels, scientific workers use the definitions of the American administration, so looking at the aforementioned as well as the works of numerous colleagues from the USA, we can say that online radicalization is a complex process in which the victim through online communication is exposed to such content that creates an opinion for him and in more severe forms encourage actions that justify, support, encourage or carry out violence as a legitimate way to achieve political goals.

When we talk about the possibilities of the state to respond to the harmful effects of certain Telegram channels in the Republic of Serbia, there are two directions of action (Đukić, 2023). The first is that the Republic of Serbia communicates with Telegram through its official structures in this case and demands the cancellation of channels that serve for radicalization. In this case, international security cooperation is more than desirable in order for countries to warn each other about telegram channels that appear among their population, as well as for the exchange of experiences in the fight against such phenomena.

For this purpose, the Republic of Serbia would have to accept, as soon as possible, the invitation that has been available to it for years, to become part of the European Centre for Defence against Hybrid Threats in Finland, which has sufficient capacities to overcome the aforementioned threats (Zivotic, 2022). The second course of action defines the role of the state apparatus to publicly warn citizens about such channels as well as to work on the digital literacy of its citizens in order to increase the population's resistance to radicalization attempts and the influence of fake news. Unfortunately, due to the quietness of the administration, this role in the Western Balkans has been assumed by some NGOs and independent analysts like the authors of this article. To this should be added the use of counter-narratives by the holders of the highest state positions, who should publicly present denials of the claims that appear on Telegram channels on the recommendation of the security services as well as after their content analysis. Unfortunately, such examples in the Western Balkans are very rare so far, and the use of counter narratives was only used if someone on the mentioned Telegram channels dared to directly insult some of the government officials.

The aggravating circumstance in this struggle is that Serbia is not a member of the EU. Cooperation with EUROPOL is limited to two representatives to which Serbia is entitled as an associate, not a full member of this European police organization. The capacity for cooperation that Serbia can achieve with the EUROPOL unit on reporting online content that serves to radicalize is debatable. In the prevention of radicalization, religious leaders also play a big role, so the Belgrade Imam Mustafa Jusufspahić has a very effective account on the X platform, where he is followed by believers of all confessions because of his views that call for peace, togetherness and coexistence, and where he directly opposes extremists who abuse Islam for their own purposes.

The former Archbishop of the Catholic Church in Serbia, Hočevar, behaved similarly in the media and in public addresses. On the other hand, dignitaries of the Serbian Orthodox Church who publicly criticized Russian aggression against Ukraine were attacked not only by the public but also by many of their colleagues, while the Serbian Orthodox Church never publicly dissociated itself from calls for the armed defense of Orthodoxy by citizens of Serbia fighting on the Russian side. on the battlefield in Ukraine sent many times precisely through the Telegram channel. Their maximum in their addresses is to maintain a neutral position, while numerous associations close, especially to certain church dignitaries of the SPC in Montenegro, openly support Russian aggression, thus practically continuing the hybrid actions from the aforementioned Telegram channels, convincing the faithful that the mother church of the Serbian Orthodox Church is the Russian Church, directly promoting falsehood. The true is that the Serbian Orthodox Church received autocephaly from the Patriarchate of Constantinople, as did the Russian Orthodox Church 200 years later.

Conclusion

Telegram is very agile tool for information influence operations. No doubt abuse of Telegram contributes to security challenges, threats and risks. The speed of spreading falsehoods can contribute instability, eroding of trust to the institutions and can cause violence. Lack of monitoring capabilities is immanent. Resources dedicated for monitoring of Telegram should be increased before carriers of propaganda and disinformation develop full capabilities of influence on certain population. With no doubt today, we can speak about Telegram followers as unique stratus of society.

Russia will further invest in its activities on Telegram. Training and call for action for new digital “warriors“ is on-going activity.

To counter malign influence on Telegram we need strong strategic communications. Beside that we also need a capable continuous threat assessment which can include state and non-state resources. New research should have focus on main drivers and techniques which will help us to understand influence information operation.

International collaboration and exchange of experience can help modern democracies. Telegram terms of policy favor’s spread of disinformation. On Western Balkans and in Serbia specific pro-Russian Telegram channels have capacities to influence internal politics, mobilize citizens for actions and more than that content from those Telegram channels reaching one part of mainstream media. Process of radicalization, targeting of anti-Putin voices with calls for assassination is shared freely without consequences.

Establishing of regional Counter disinformation center can be logical first step to counter challenges which we have elaborated in this work.

Literature:

1. Aliaksandr Herasimenka, Jonathan Bright, Aleksi Knuutila & Philip N. Howard (2023) Misinformation and professional news on largely unmoderated platforms: the case of telegram, Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 20:2, 198-212

DOI: 10.1080/19331681.2022.2076272

2. Backes, Oliver and Andrew Swab (2019). “Cognitive Warfare: The Russian Threat to Election Integrity in the Baltic States.” Paper, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School

3. Burns, Megan (1999), “Information Warfare: What and How?” CS.CMU, Carnegie Mellon University

4. Bodine-Baron, Elizabeth, Todd C. Helmus, Andrew Radin, and Elina Treyge (2018), Countering Russian Social Media Influence. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation

5. Curry, B. (2023), Most Popular Apps, Available at https://www.businessofapps.com/data/most-popular-apps/

6. Center for Strategic Analysis (2022) Spread of Russian propaganda on Western Balkans - Case Study Serbia, Available at https://www.czsa.org/single-publicaiton/18 accessed 2.11.2023.

7. Dean, B. (2023), How Many People Use Telegram, Available at https://backlinko.com/telegram-users accessed 2.11.2023

8. Department of Homeland Security (2018), Foreign Interference Taxonomy, Available https://www.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/publications/foreign_interference_taxonomy_october_15.pdf, accessed 3.11.2023.

9. DFRlab (2023), Networks of pro-Kremlin Telegram channels spread disinformation at a global scale, Available at https://medium.com/dfrlab/networks-of-pro-kremlin-telegram-channels-spread-disinformation-at-a-global-scale-af4e319bd51e, Accessed 5.11.2023.

10. Ecker, U.K.H., Lewandowsky, S., Cook, J. et al. (2022) The psychological drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction. Nat Rev Psychol 1, 13–29 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-021-00006-y

11. Eric V. Larson (2022), Understanding Commanders’ Information Needs for Influence Operations, Santa Monica: Rand Corporation

12. European Union External Action (2023), Report on Foreign Information, Manipulation and Interference Threats, Available from https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/2023/EEAS-DataTeam-ThreatReport-2023..pdf, accessed 10.11.2023.

13. European Commission, A Counter-terrorism Agenda for the EU: Anticipate,Prevent, Protect,Respond Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020DC0795&qid=1631885972581, accessed 10.11.2023.

14. EU Commission (2022), D2022 Code of practice on Disinformation, Available at https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/code-practice-disinformation accessed 10.11.2023.

15. Gočanin, S.(2023), Opet Bez Neophodne Većine za Uvodjenje Sankcija Rusiji, Radio Slobodna Evropa-Srbija, Available at https://www.slobodnaevropa.org/a/srbija-rusija-sankcije-odbor-skupstina-spoljni-poslovi/32377493.html, accessed 10.11.2023.

16. Grisé, Michelle, Alyssa Demus, Yuliya Shokh, Marta Kepe, Jonathan W. Welburn, and Khrystyna Holynska, (2022) Rivalry in the Information Sphere: Russian Conceptions of Information Confrontation. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation

17. Julie Celine Bergaust & Stig Rune Sellevåg (2023) Improved conceptualising of hybrid interference below the threshold of armed conflict, European Security, DOI: 10.1080/09662839.2023.2267478

18. Kešmer Meliha (2022) Globalna teroristička pretnja raste, navodi EUROPOL, Radio Slobodna Evropa, Svijet https://www.slobodnaevropa.org/a/terorizam-evropa-prijetnja-balkan/32462667.html, accessed 20.11.2023.

19. Harris, K.R.(2022), Real Fakes: The Epistemology of Online Misinformation. Philos. Technol. 35, 83 https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-022-00581-9

20. Kenyon Jonathan, (2021) Exploring the role of the Internet in radicalization and offending of convicted extremists, Ministry of Justice Analytical Series, London

21. Li, J., Chang, X. (2023), Combating Misinformation by Sharing the Truth: a Study on the Spread of Fact-Checks on Social Media. Inf Syst Front 25, 1479–1493 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-022-10296-z

22. Mitchell, K. J. & Johnson, M. K. (2009) Source monitoring 15 years later: what have we learned from fMRI about the neural mechanisms of source memory? Psychol. Bull. 135, 638–677

23. Životić I., Obradović D. (2023), SPREAD OF SOFT POWER BY AUTHORITARIAN REGIMES ON WESTERN BALKAN IN CONTEXT OF GLOBAL COMPETING, Security Horizons, Faculty for Security, Skopje DOI: 10.20544/ICP.2.5.21.P18

24. Životić I., Obradović D. (2023), SPREAD OF THE RUSSIAN PROPAGANDA ON WESTERN BALKANS – CASE STUDY IN SERBIA, Security Horizons, Faculty for Security, Skopje DOI: 10.20544/ICP.3.7.22. P15

25. Zivotic, I.(2022) Dojave o bombama, šta smo naućili, Centar za stratešku analizu, Beograd Available at https://www.czsa.org/single-analysis/88/dojave-o-bombama-u-srbiji-sta-smo-naucili accessed 20.11.2023.

26. Pantazi, M., Kissine, M. & Klein, O.(2018) The power of the truth bias: false information affects memory and judgment even in the absence of distraction. Soc. Cogn. 36, 167–198

27. Rogers, R. (2020). Deplatforming: Following extreme Internet celebrities to Telegram and alternative social media. European Journal of Communication, 35(3), 213–229. doi:10.1177/0267323120922066

28. Tucker, Robert C., (1957), The Psychological Factor in Soviet Foreign Policy. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation,

29. Trauthig, I. K. (2022, March 27). Chat and Encrypted Messaging Apps Are the New Battlefields in the Propaganda War. Lawfare.

30. Đukić Simeon, (2023) On line radikalizacija na Zapadnom Balkanu, Trendovi i Odgovori, Evropska Komisija

31. Živanović, M., Komarčević,D.(2022) Kako su Proruski i Ruski Telegram Kanali Širili Dezinformacije o Kosovu, Radio Slobodna Evropa-Srbija Aviable at https://www.slobodnaevropa.org/a/kosovo-rusija-telegram-proruski-drustvene-mreze-dezinformacije/31969041.html,accessed 30.11.2023.

Figures :

32. Similarweb (2023), Popularity of communication applications in Serbia, Available at https://www.similarweb.com/top apps/google/serbia/communication/ accessed on 12.12.2023.

33. DFRLab (2023), List of Russian Telegram channels created with same purpose for different countries, Available at https://medium.com/dfrlab/networks-of-pro-kremlin-telegram-channels-spread-disinformation-at-a-global-scale-af4e319bd51e accessed 5.11.2023.

Cite this article:

APA 6th Edition

Životić, I. i Obradović, D. (2024). Telegram as a Specific Playground of the Kremlin's Information Operations in Serbia. National security and the future, 25 (1), 65-92. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.25.1.3

MLA 8th Edition

Životić, Ilija i Darko Obradović. "Telegram as a Specific Playground of the Kremlin's Information Operations in Serbia." National security and the future, vol. 25, br. 1, 2024, str. 65-92. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.25.1.3. Citirano DD.MM.YYYY.

Chicago 17th Edition

Životić, Ilija i Darko Obradović. "Telegram as a Specific Playground of the Kremlin's Information Operations in Serbia." National security and the future 25, br. 1 (2024): 65-92. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.25.1.3

Harvard

Životić, I., i Obradović, D. (2024). 'Telegram as a Specific Playground of the Kremlin's Information Operations in Serbia', National security and the future, 25(1), str. 65-92. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.25.1.3

Vancouver

Životić I, Obradović D. Telegram as a Specific Playground of the Kremlin's Information Operations in Serbia. National security and the future [Internet]. 2024 [pristupljeno DD.MM.YYYY.];25(1):65-92. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.25.1.3

IEEE

I. Životić i D. Obradović, "Telegram as a Specific Playground of the Kremlin's Information Operations in Serbia", National security and the future, vol.25, br. 1, str. 65-92, 2024. [Online]. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.25.1.3