u knjizi Blurring the Truth - Disinformation in Southeast Europe / Nehring, Christopher ; Sittig, Hendrik (ur.). Sophia, Berlin: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Media Programme Southeast Europe, 2023.

CROSBI ID: 1265808

Naslov poglavlja u knjizi

Disinformation, Propaganda and Fake News in Croatia

Autor

Akrap, Gordan

Vrsta, podvrsta i kategorija rada

Poglavlja u knjigama, znanstveni

Knjiga

Blurring the Truth - Disinformation in Southeast Europe

Urednik/ci

Nehring, Christopher ; Sittig, Hendrik

Izdavač

Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Media Programme Southeast Europe

Grad

Sophia, Berlin

Godina

2023

Raspon stranica poglavlja

95-113

ISBN

978-3-98574-110-6

Izvorni jezik

Engleski

Znanstvena područja

Informacijske i komunikacijske znanosti, Sigurnosne i obrambene znanosti, Vojno-obrambene i sigurnosno-obavještajne znanosti i umijeće

Ustanove:

Sveučilište Sjever, Koprivnica

Profili:

Gordan Akrap (autor)

Gordan Akrap (autor)

Blurring the Truth - Disinformation in Southeast Europe / Nehring, Christopher ; Sittig, Hendrik (ur.). Sophia, Berlin: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Media Programme Southeast Europe, 2023

Preface:

Disinformation in Southeast Europe

By Hendrik Sittig

Dear Readers,

Disinformation is not a new phenomenon. Disinformation existed hundreds of years ago. Today, however, it is becoming much more widespread and powerful thanks to the internet and social networks in particular. Moreover, the spread of fake news has increased in recent years - and with the Covid pandemic and the Russian war of aggression in Ukraine, it has reached new dimensions. Disinformation and fake news are the digital plague of our time. They threaten our democratic society. They polarize, divide and destroy. And most of the time, they are deliberately produced and disseminated for precisely this reason. Russia, in particular, has made this dirty game a permanent instrument of its politics at the international level. The Kremlin has repeatedly tried to divide liberal democratic societies and to influence elections and political decisions in other countries with targeted campaigns. But also domestically, disinformation is repeatedly used in many countries to discredit political opponents.

It is absolutely clear: democracy relies on pluralism, it needs pluralism - that is, many opinions that lead to a decision in the social process. But the information through which we form our opinion must be true. It has to be true especially when used as a basis for making political decisions. Anything else would be fatal. Viewed from this vantage point, democracy has begun easing into a pathological state when responsible politicians present false information as “alternative facts” and talk about a “post-truth era” in which feelings and personal convictions are more important than facts and the truth.

The countries in Southeast Europe in particular seem highly susceptible to disinformation campaigns. Poorly financed mainstream media, less evolved media competence and a low level of trust in the work of journalists provide an ideal breeding ground for the spread of false information. At the same time, simmering ethnic conflicts, such as the one between Serbia and Kosovo, or the politically complicated situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina are ideal starting points for fueling tensions, sowing mistrust and further destabilising fragile societies.

With this book, the Media Programme of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung aims to give an overview of the current situation in the ten countries that the Media Programme observes in Southeast Europe. What kind of disinformation campaigns are there? How do they spread? What role do foreign as well as domestic actors play? What countermeasureips are already being taken?

I would like to thank to all of the authors, who are proven experts in the field in their respective countries, and especially to Dr. Christopher Nehring, guest lecturer of our Media Programme at Sofia University on “Media, Disinformation and Intelligence Services”, who curated this book.

Hendrik Sittig

Director of the Media Programme Southeast Europe of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung

Sofia, 2023

Introduction: Disinformation Today

By Christopher Nehring

Why Disinformation Matters

When the editors first had the idea to compile this volume, the war in Ukraine and the disinformation that followed in its wake were still a faraway nightmare. Before the Russian attack on Ukraine, disinformation about the COVID-19 pandemic was still topic number one. This changed dramatically during the time the editors and authors of this volume strove to compile an overview of disinformation in Southeast Europe. Yet, as all regional case studies of this volume demonstrate, the topics and content of disinformation may vary, but the patterns, actors and above all, the aim of disinformation is remarkably persistent: by sowing discontent, deepening societal, political, ethnical, racial or economical conflicts and polarizing societies, alliances and partners, disinformation is employed to undermine democracy, its institutions, representatives and foundations. The major threat today’s postmodern, digital and globalized disinformation poses is an attack on the very foundation of democracy. By blurring and undermining categories such as truth, facts or scientific knowledge, disinformation “corrodes the foundation of liberal democracy, our ability to assess facts on their merits and to self-correct accordingly.”1 Hence disinformation is much more than just a bundle of more or less elaborate lies, smear campaigns or covert political propaganda. By attacking our belief in the very existence of truth and facts “disinformation campaigns are attacks against a liberal epistemic order, or a political system that places its trust in essential custodians of factual authority. These institutions – law enforcement and the criminal justice system, public administration, empirical science, investigative journalism, democratically controlled intelligence agencies – prize facts over feelings, evidence over emotion, observations over opinion. They embody an open epistemic order, which enables an open and liberal political order; one cannot exist without the other.”2 This is what makes disinformation so dangerous – and why any modern, digital democracy and media system needs profound knowledge about the purpose, patterns, topics and actors of disinformation. And thus, the study of disinformation leads the way towards a more resilient society, media and politics.

About this Book

This is neither the first nor the last study of disinformation. Yet it differs significantly from others in many regards. Firstly, it is the first and only study summarizing the state of disinformation in Southeast Europe. While regional studies abound, none so far has looked at all countries of the region between the Danube and the Mediterranean in a single comprehensive analysis. Secondly, this volume not only generates a concise overview of disinformation in the SEE region, but does so by explaining specific case studies, addressing current questions, showing the sources, potential, consequences, forms, narratives and a variety of countermeasures against disinformation in the region at large. Hence, the study not only explains and demonstrates the negative effects of disinformation, but also strives to point to approaches on how different countries deal with disinformation and thus how societies can become more resilient against the manipulative use of information.

Even though bringing together 12 authors from as many countries has been a challenging task, this volume is a testament to the successful collaboration of authors with different backgrounds and perspectives. To achieve this, we deliberately decided to present the findings and results of our research, observations and analyses in a language and style understandable to the common reader without prior expert knowledge of either the region or disinformation. To unify all case studies, the editors and authors of this volume agreed upon a common structure for the articles. This structure builds upon six analytical subcategories: (1) Terminology and definitions; (2) Audience and perspective; (3) Narratives, case studies and examples; (4) Media, sources, multipliers of disinformation; (5) Political context; (6) Countermeasures and resilience.

Last but not least, it goes without saying that disinformation is a global and dynamic phenomenon. This means that some of the more specific results or case studies in this volume may become obsolete within a certain amount of time. Yet, its focus on the big picture and general trends of disinformation in Southeast Europe ensure that we will make a significant contribution to a better understanding of disinformation in our time. Here, the Russian war in Ukraine and its repercussions in SEE has once again demonstrated how long disinformation in this region of geostrategic importance has not received the attention it deserves.

Terminology: A Beast with many Names

What is disinformation? Defining what we mean when we use the term “disinformation“ is no easy task. Likewise, focusing on terminology and the definition of disinformation is not a vain academic undertaking. Defining the meaning of “disinformation” is an act of power: The power to accuse an opponent of using improper, illegal and unethical instruments, the power to stigmatize information as untrue or illegitimate and the power to censor, ban or delete this information. Similar to the terms “propaganda” and “fake news”, “disinformation” has turned into a slogan or even polemic used in societal and political discourse and mutual accusations or employed by populist politicians to reject criticism.3 Yet, defining “disinformation” also matters outside of political discourse. Internet companies and social media platforms, for example, not only define “disinformation”, but also to act upon that definition when flagging or deleting certain content. Deleting or flagging a tweet, post or video thus becomes a real-life demonstration of what power over public discourse means – and why definitions matter.

In today’s political and public discourse there are many different terms used to describe forms of information manipulation and the manipulative use of information. Or in other words: disinformation is a beast with many names! So many names that they are often – and incorrectly – being used interchangeably. The most prominent terms include: Disinformation, fake news, misinformation, hybrid warfare, information war, propaganda, active measures, strategic communication, influence operations, psychological or political warfare and deception operations. Yet, while all forms of information manipulation and the manipulative use of information share some common features, not all of them are disinformation. One might even argue that blurring the understanding of what disinformation is and what, for example, sets it apart from propaganda, is an effect of disinformation itself.

Probably the most common definition of disinformation in today’s political discourse was put forward by the European Commission in 2019: “Disinformation is false, inaccurate, or misleading information designed, presented and promoted for profit or to intentionally cause public harm.”4 And while this definition certainly captures most features commonly associated with disinformation, it misses some: First of all, one can argue that the definition also applies to propaganda, fake news or (dirty) PR-campaigns; secondly, it does not include any information about the actors and origins

of disinformation; and, thirdly, it misses the main purpose and aim of disinformation: to not (only) cause public harm or generate profit, but to exert influence. This influence most often (but not exclusively) is political, and most often achieved by “negative” means, i.e., by sowing discontent, deepening societal, political, ethnical, racial or economical conflicts and polarization and undermining trust in democracy, institutions, facts etc.5

Taking the EU definition of disinformation as a basis, this study will use the term as meaning “false, inaccurate, decontextualized and misleading information COVERTLY and DELIBERATLY designed, presented, promoted and spread to manipulate and exert political, financial or other influence”. This definition has certain advantages. First of all, it specifies that disinformation – unlike misinformation – is knowingly and deliberately designed and spread as a means to exert influence.6 Secondly, it focuses on the exertion of influence as the main purpose of disinformation which includes other purposes, such as profit or causing public harm. And thirdly, this definition specifies that disinformation, unlike, for example, propaganda, usually disguises its origins and authors via elaborated schemes. This is also what sets propaganda—today understood as strategic manipulation of a large audience by governments or powerful actors7—aside from disinformation. There are extended debates in academic discourse whether disinformation should be categorized as a subcategory of propaganda or whether propaganda is another form of disinformation. This study argues the former. US institutions, for example, up until the 1980’s used the characteristic of hidden and covert origin of information meant to influence political and other events, organizations or groups, as their main criteria to differentiate between various forms of political influence: Covert or “black” propaganda” was opposed to official, overt or “white” and “grey” propaganda via semi-official institutions.8 Historical approaches to disinformation have focused on the genesis of disinformation as military and intelligence deception operations and hence correctly asserted that due to its clandestine nature and covert origin “disinformation was, and in many ways continues to be, the domain of intelligence agencies.”9

Applying this definition to certain Russian actors of disinformation may demonstrate the significance the question of covert or overt origin of manipulative information has: Official or semi-official Russian media outlets such as RT or Sputnik – while certainly deliberately spreading untrue or decontextualized information to manipulate and exert influence – have to be labelled “grey propaganda” or simply “propaganda”, as their relation to a state actor pursuing an official agenda is known. Accordingly, disinformation is the term reserved for manipulative information spread by actors such as, for example, “Redfish” or “Maffick Media”, front companies who pose as PR-companies or media outlets, while in fact being directly linked to the Russian state and covertly spreading misleading information to exert political influence.10

Thus, the question of definition and terminology is very important for the articles in this volume. It is one of the goals of this study to show and discuss the most common terms and definitions used in the countries of Southeast Europe and ask the question who and how has defined what disinformation has come to mean. In this regard, the results of the case studies highlight the problem: in general, definition and terminology receive little attention in Southeast Europe – with severe consequences for the fight to make societies more resilient against manipulative information. In most countries, the generic term “fake news” – meaning everything from covert political propaganda to poor and sensational journalism – is the most common term used to describe the manipulative use of information. In Montenegro, for example, the term has even found its way in the Criminal Code, while, at the same time, remaining unspecified. It thus comes as no surprise that malevolent politicians and pressure groups in the region happily apply and reinforce the term “fake news” to discredit any criticism and/or attack from the media, journalists or political opponents. This trend also shows that having a clear definition and distinction between different kind of manipulative information might be a first step in the fight against disinformation and towards a more resilient society.

Narratives and Case Studies of Disinformation

What is the content of disinformation campaigns and which geopolitical narratives does disinformation promote in Southeast Europe? This is one of the key questions every author of this study has attempted to answer and describe by drawing on empirical examples.

While Propaganda seeks to incite and rally support for a cause and to persuade a given target group of an idea, ideology or product, the content and narratives of disinformation are negative and disruptive. Instead of rallying support for Communism (which was the task of official and unofficial propaganda), for example, Soviet disinformation narratives focused on undermining Western democracy, liberalism or capitalism. This trend continues in today’s Russian disinformation whose general narratives focus on undermining trust in and credibility of democracy, the state of law and liberalism and all its institutions.11 The majority of disinformation today appears as “anti-narratives”: anti-US, anti-NATO, anti-EU, anti-natural-Covid-origin, anti-Covid-vaccinations, anti-Ukraine, anti-LGTBQ, anti-pluralistic etc. Disinformation feeds on conflict while trying to intensify conflict, cleavages, differences, mistrust and discontent.

As all case studies of this volume suggest, there are three main topics and narratives that dominated disinformation in Southeast Europe during the past years: (1) Covid-related disinformation; (2) Nationalism and ethnic conflict; and (3) the Russian war in Ukraine and its repercussions throughout the region.

Introduction: Disinformation Today

These three narratives are explained at length for each country of the region in the studies include in this volume.

In general, disinformation narratives show a high degree of adaptiveness and flexibility, always adjusting their focus to the latest hot topic and the headlines of the day. Today’s digital disinformation does not strive to create long-lasting, holistic and elaborated master narratives. Today’s disinformation narratives are loud, shrill, fast, often contradictory and seemingly provide easy answers to complex political and societal problems. Russian disinformation, for example, adapted the 1980’s disinformation campaign about an alleged artificial origin of the AIDS-virus as an US-bioweapon-experiment both during the Covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine.12 China, on the other hand, tried to spread narratives during the Covid-19 pandemic that stressed an alleged failure of Europe’s Covid containment measures as a marker of the inferiority of European democracy as opposed to “the Chinese model”.13 And Covid disinformation itself has two majors narratives. The first, which has lost both in quality and in quantity over the years, focused on an alleged artificial origin as a part of a global (Chinese, US, Russian, big money- or other) conspiracy; and the second on discrediting anti-Covid vaccines.14

Another very important and representative example of disinformation narratives in Southeast Europe is nationalism and ethnic conflict. While ever since the days of Imperialism the big powers have used conflicts between ethnic groups and nationalism as a tool to instigate and activate conflict, this narrative is particularly important in the Southeast Europe today. As the studies of this volume clearly show, nationalist groups in all countries of the region are particularly active in using and spreading disinformation. Here, they can also count on official and covert Russian support, since nationalist movements of the region are opposed to both NATO and the EU (which in turn serves Russian interests). Nationalist movements are not only active in spreading disinformation. Nationalism is also one of the most important narratives and content of disinformation in the SEE region. The studies of this volume provide ample evidence for that, for example the Bulgarian-North Macedonian conflict over EU-accession or the study of Bosnia where political elites use disinformation to uphold ethnic division and electoral ethno-national mobilization.

As the studies also show, the Russian war in Ukraine and the following EU and NATO initiatives for increased cooperation and EU enlargement in the SEE region has triggered a new wave of anti-NATO, anti-EU- and pro-Russian disinformation. It is no surprise, as all studies mention, that the second side of Russian disinformation following the war in Ukraine sees increased ethno-nationalism and an intensification of ethnic and national conflict. Again, the disinformation over the conflict of EU accession of North Macedonia and the Bulgarian veto against it is one of the most obvious examples.

The Target Groups of Disinformation: Audience and Perspectives

Most studies of disinformation focus on the perpetrators – the authors, producers and distributors of disinformation. And while identifying and understanding their strategies, instruments and motives is certainly of the utmost importance, we should never forget that disinformation is custom-made and specifically designed for an audience. The challenges and problems disinformation pose vary according to the perspective of the observer and the recipients of disinformation: for journalists, the challenge is to judge the trustworthiness and truthfulness of information and not to allow themselves to be instrumentalized as an accelerator and mouthpieces of disinformation. For them checking facts, recognizing and debunking disinformation as well as countering disinformation with proper journalism are the most important tasks. As studies suggest, it is in fact quality media that is the most powerful (yet unintentional) multiplier of disinformation. So, for example, one of the most powerful images published by the Russian troll factory “Internet Research Agency” during the Trump election campaign, the so-called “Jesus-ad”, did not reach more than a handful of followers on Facebook – but an audience of millions when published on the frontpage of the New York Times as part of

an article on Russian election interference.15 This poses a huge dilemma for serious journalism: with their reporting, even if debunking, journalists may actually help disinformation reach a significantly broader audience outside its own echo chambers.

While multiplying disinformation may be the biggest challenge for journalists and the media, the main problems for their readers—and viewers and for political and public discourse in general—is that they are the main targets that disinformation seeks to influence. For these target groups, the main challenge is to recognize disinformation and the rationale behind it and to become resilient against the manipulative use of information and attempts at exerting covert influence. In this volume, each author takes these different perspectives and target groups into account and assesses the challenges disinformation poses in his/her country from their perspective, discussing how they are being dealt with. As the studies reveal, a major problem for all target groups of disinformation in the SEE region is their interconnectedness. Politicians, for example, are not only a main target of disinformation, but they and the political parties they belong to are also a major force in spreading disinformation. In Bosnia, for example, several examples of party-political “troll farms” with interconnected farms of web portals have come to light. Hence, the same is true for journalists and the media in general: while quality media is the second main target group of disinformation, tabloids, party-political outlets or notable foreign propaganda, such as the Russian Sputnik in Serbia, are themselves dynamic actors in spreading disinformation. As a result, the general public, which is the third main target group for disinformation,

is confused, disorientated, disappointed and easily mislead. While surveys from most countries show that the majority of people think they come into contact with manipulated information on the regular basis, they have a hard time defining what disinformation is, where it comes from and, most of all, to attribute disinformation to its origins. Media illiteracy is a major factor in all SEE countries and plays a very important role in the reaction of the public towards disinformation. Mistrust, disbelieve and confusion in the public domain and political communication are a result of this complex situation.

Media, Sources and Multipliers of Disinformation

Disinformation is in many ways closely tied to and shaped by the media via which it is spread. Classic, analogue disinformation was spread via press articles, books, posters, leaflets/flyers, letters, movies, documentaries, rumours, interviews or radio shows. Today, the overwhelming majority of disinformation – in Southeast Europe just like anywhere else – is spread online via websites, posts, images, videos, commentaries, leaks, ads or memes. The head of the Soviet intelligence service’s disinformation unit Ivan Agayants is reported to have stated: “Sometimes I am amazed by how easy it is to play these games. If they did not have press freedom, we would have to invent it for them.”16 A postmodern modification of Agayants’ saying might read: “If the internet did not exist, we would need to invent it for disinformation.”

In many ways, online communication and digital culture form the perfect conditions for disinformation. Due to the characteristics of online communication the online sphere has made disinformation a lot faster, easier, cheaper and more direct. Facilitation, amplification, acceleration and globalization are thus some of the main features of digital disinformation. “Troll factories”, such as the infamous Russian “Internet Research Agency”, or automated programmes designed to manufacture and spread disinformation (bots)” are two of the most obvious testimonies of this development.

Furthermore, the digital sphere provides the actors and authors of disinformation with easier and better cover of anonymity compared to the analogue world. Amongst the most famous methods and tools of digital disinformation are, for example: “Hacking and leaking secret information” and setting up huge quantities of fake websites, fake accounts and fake profiles. High-profile actors of disinformation even use “false flag”, “double deception” or “spoofing” techniques, copying the technology, language, symbols and outlets of known hacker groups, terrorist organisations, intelligence services or serious media outlets.17 In other cases, known state propaganda outlets create affiliates, officially engaging in PR, journalism or advertising, while in fact being run by government-affiliated journalists and spreading political disinformation. Some examples include the Berlin-based media outlets “Maffick Media” or “Redfish”, daughters of RT’s video outlet “Ruptly”, staffed with RT-journalists.18 And while Russia and China19 are suspected to be the main actors of disinformation in the SEE region, tracking disinformation all the way back to its true origins and attributing it to an institution or individual has become a lot harder (and often impossible). Just like hacks, cyberattacks and acts of cyber espionage, the fight against disinformation struggles with its very own “attribution problem.”20

Playfulness, gamification and cross-mediality are other characteristics of today’s disinformation that are heavily influenced by digital media.21 Social media memes or video-clips about the war in Ukraine, designed to spread false or misleading information and trigger strong emotions amongst a (mostly very young) audience22, are a case in point. Here, text, images, memes, caricatures, sounds and videos are employed to spread disinformation. In the age of social media, the content and the form of digital disinformation have thus become increasingly interwoven.

Last but not least, one of the most important characteristics of disinformation in the digital age is that unlike disinformation during the Cold War, disinformation today does no longer present or advance “master narratives” about events, conflicts or persons. Disinformation in the digital era presents a plurality of different “alternative explanations”, none of which is holistic, all-encompassing or even coherent, but all of which combined, seek to undermine the very existence of truth or facts as such.23 Covid-related disinformation as opposed to AIDS-related disinformation in the 1980’s are a telling example: during the 1980’s the Soviet secret service KGB invented and spread the conspiracy theory according to which the then new human insufficiency virus (HIV) had been artificially created by the US Pentagon as a bioweapon and spread around the world after being tested on prisoners.24 At the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, a plurality of adapted versions of this “artificial origin theory” were spread. Yet, the differences soon became apparent: Covid-related disinformation did not seek to present one singular, coherent “Covid master narrative” about the pandemic and its consequences. Instead, Covid-related disinformation pushed for broad variety of different narratives, such as the “Wuhan-Lab-Theory” or vaccination-related conspiracy theories (“microchips and Bill Gates”). None of these theories were elaborate enough to incorporate the origin, the political and economic consequences AND the new vaccines at the same time. Instead, disinformation focused on undermining public trust in everything – public health systems, science, the political system, vaccination or the pharmaceutical industry. This cacophony of crude theories was not meant to persuade – it was meant to plant doubt, to distract and disturb, to spread mistrust, fear and uncertainty. And, as all studies in this volume suggest, in SEE countries, Covid-19 disinformation, sadly enough, was very successful. Mistrust against governments and political communications, the instrumentalization of the pandemic in election campaigns and media illiteracy played a crucial role for Covid disinformation across the entire region. As a result, vaccination rates in all countries in the region remained low, while death rates remained above the European average.

A last important feature of digital disinformation is its privatization and commercialization. Most public and academic discourse focuses on state organized and state sponsored disinformation. Yet, at the same time, commercial disinformation is very often overlooked, but no less problematic. Not every pro-Russian or Covid-denialist website is run by the Russian state or PR-companies secretly owned and run by intelligence officials. In the digital age, posting and spreading crude, extremist, denialist, anti-liberal or pro-Russian disinformation has turned into a lucrative business model. While

in Germany, for example, marketing and PR companies offer fake online ratings for all sorts of businesses25, and the French football club Paris St. Germain was accused of entertaining its very own “troll factory” to smear players, agents and journalists26, Southeast Europe knows several examples of commercialized political disinformation run by private, non-state affiliated individuals for monetary reasons. The town of Veles in North Macedonia, for example, became world famous for its “fake news industry” during the 2016 US-presidential election. Several dozens of websites, posting and reposting pro-Trump and/or anti-Hillary Clinton content were run by smalltown adolescents, some of which earning the poor youths more than 10.000 US-$ month.27 A similar model, but with Russia-related content was revealed to journalists in Bulgaria: “Dimitar”, a private operator of numerous fake news websites, had also set up websites and social media profiles posting and re-posting pro-Russian and anti-Western disinformation for the solemn reason of generating clicks and online user interaction which earned him money via ad placements.28 Commercial disinformation like this is not only often overlooked, but also frequently dismissed as less harmful or less important. Yet, while commercial disinformation might be only the “ugly cousin of political disinformation”, it is disinformation nonetheless with anonymous authors intentionally repeating, designing and spreading malign content. And even though their personal interest might not be political, the results certainly are. Commercial disinformation revolves around and feeds on political disinformation like a parasite, accelerating and amplifying its magnitude and effects. Thus, in many ways the commercialization of disinformation, turning old-fashioned dezinformatsiya into todays “disinformation industry” with an economic model of its own, is the very epitome of the interconnectedness between disinformation and media, between content and form – between disinformation and the internet.

Political Context

Today’s digital disinformation is a truly global phenomenon. However, its forms, content and underlying mechanisms are designed to affect smaller entities such as national states or specific groups in society. There, regional specifics play an important role. Producing, adapting and designing disinformation

for SEE countries needs to take into account the particularities of the region. When political movements, parties or other actors are being supported as part of influence campaigns or when politicians or other important figures are smeared and discredited, political and media culture play an important role. Insider reports and investigations of the infamous Russian troll factory “Internet Research Agency” in St. Petersburg, for example, have shown how the production of large-scale disinformation is organized by different departments within one larger unit, each department focusing on one region, country or language.29

This is what we mean when we talk about the political and national context of disinformation, which is an important point of reference for our analyses. Struggling with national and ethnical conflict and being at the geographical crossroads between Europe and Asia and political crossroads between NATO and EU on the one hand and China and Russia on the other, Southeast Europe is today a hotspot for disinformation. The analyses presented in this volume show remarkable results regarding the political context of the most thriving topics of disinformation during the past years:

Disinformation about the Covid-19 pandemic reflects global conspiracy theories and disinformation, and needed little adaption to the political context of SEE countries.

Quite the contrary is true for disinformation about the Russian war against Ukraine. Here, narratives, topics and campaigns are designed for each country and its political landscape individually. This plays an important role for the content of disinformation, for example, whether a country is a member of NATO and the EU or not. This was not only true for the question of embargos and sanctions, but also concerning general anti-NATO sentiment or “neutralist” or “sovereigntist rhetoric” (e.g. in Romania). Disinformation about the war in Ukraine is heavily influenced not only by regional and national political context, but also by the wider geopolitical context. One example of this are disinformation campaigns against the accession to the EU of several countries in Southeast Europe, e.g. in Bulgaria and North Macedonia.

Nationalism and ethnic conflict (or nationalistic conflict with neighbouring countries) are perhaps the most important element of the political context against which disinformation in the SEE region is produced and spread. In Bosnia, for example, conflict between the three main ethnic groups is the most important point of reference for disinformation.

In most countries foreign countries – Russia and, to a lesser degree, China and Turkey – are very active actors of disinformation. Domestic groups, parties or movements, however, also play a crucial role: one the one hand, they often function as proxies for foreign (mostly Russian) interests. On the other hand, they also utilize disinformation as a weapon in domestic politics and as means to pursue their own interests. In Bosnia and Montenegro, to name only two, parties are known to have their own “troll farms” with an interconnected system of websites, portals and social media profiles as outlets for (domestic) disinformation. In Romania, similar mechanisms are used by political parties and business interests to discredit anti-corruption measures as being part of a “deep-state conspiracy”.

Countermeasures and Resilience

How to fight disinformation and make our societies more resilient against the manipulative use of information? There are various approaches to fighting disinformation, each with its own advantages and disadvantages, some dating back decades, some children of the digital age. This study identified eleven such countermeasures:

Institutional approaches: This state-centred approach of establishing a state agency in charge of monitoring, analysing and countering disinformation has been around for a long time. The first example was the “Active Measures Working Group” installed by the US Government during the 1980’s to engage with Soviet disinformation.30 In 2021, both the Swedish and French governments, for example, revived this approached and founded state agencies engaged in identifying and debunking disinformation (“Swedish Psychological Defense Agency” and “VIGINUM”).31 Likewise, the German government established an interagency working group (AG “Hybrid”) that serves as a platform for exchange of information on developments in disinformation between security agencies and several ministries.32 The Bulgarian reformist government elected in late 2021 had similar plans to establish an interagency group of disinformation specialists, who should exchange expert knowledge, engage in debunking disinformation and making public administration more resilient.33

Since intelligence agencies are important actors in spreading global disinformation, it comes as no surprise that security policy – counterintelligence and investigative police work together with penal prosecution – has traditionally been a tool to fight disinformation.34 Yet, it seems that today’s troll factories, masquerading as PR companies or media outlets, are harder to deal with for law enforcement than old-fashioned, officially recruited “agents of influence”35. For security services to engage with disinformation there needs to be a legal basis for prosecution, e.g. anti-disinformation laws (2a) or other laws providing a legal basis to investigate and prosecute disinformation.

Debunking disinformation is another, very common approach to tackling disinformation. Engaging with disinformation, exposing its fabrication, malicious messages and untruthfulness and correcting its content seems like one of the most natural ways to counter disinformation. Here, fact-checking has been one of the most popular tools in recent years. As this volume shows, various debunking- and fact-checking-initiatives exist in almost all countries in Southeast Europe. One famous example is the fact-checking and debunking-initiative run by the European Commission’s External Action Service “https:// euvsdisinfo.eu/”. Many, but not all public media in Europe, entertain similar outlets. Yet, there is no centralized or unified approach to fact-checking and debunking, but a plurality of different initiatives and outlets within European countries. Some of them are transnational and cross-media cooperation networks of platforms and initiatives tasked with fact-checking and debunking by major European news agencies or social media networks.36 Fact-checking as a tool to fight disinformation has gained such popularity that some perpetrators of disinformation have tried to seize the format and turn it fact-checking into disinformation by developing “fake fact-checking outlets”.37

Forms of censorship, in its most neutral sense, understood as the deliberate repression of information notwithstanding the quality or origin of its content, are also one way to fight disinformation. Censorship may take on various forms, for example the legal ban of media outlets, such as the EU’s ban of RT or Sputnik after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, or the deletion of content such as posts, tweets or commentaries.

Technological, i.e. automated software, solutions play an ever more important role in this. Social media platforms have already started to employ automated software to either flag and mark and/or delete content deemed as disinformation.38 These solutions mainly tackle the technological side of disinformation such as automated “bots” spreading disinformation or so-called “deep fakes”39. Other technological countermeasures may be directed against the “economy of disinformation” and the business models behind it. Such measures include control of automated ad placement and other regulatory measures of social media platforms and “big tech” companies. Simply banning, deleting and “shadowing” them will always come late, while control or prohibition of automated distribution of advertisement provides a proactive solution against the business model behind disinformation.

While these five approaches focus on engaging with and fighting disinformation (“negative approaches”), others promote proactive solutions designed to make societies more resilient against disinformation in the first place (“positive approaches”). Here, we can observe a shift from “debunking” to “pre-bunking”, from post factum investigations and fact-checking towards “information vaccination” and “inoculation”40:

As journalists and fact checkers have asserted, simply deleting or flagging online content is not sufficient. Juxtaposing malign and questionable content with quality information and trustworthy news might be one way to break through self-reinforcing cycles of filter bubbles and echo chambers. This way, algorithm-fuelled automated content generation, suggesting “ever more of the same information” can be substituted by a “more of something else” principle.41

High quality journalism, high level journalistic education, press ethics, press freedom or, in short, quality journalism. This is true not only for the domestic realm of any given country, but also for the big Western foreign news broadcasters such as Voice of America, BBC World, Deutsche Welle or Radio Free Europe. Quality journalism generally helps make readers, viewers, politicians and also journalists less susceptible to disinformation. And while often neglected or overlooked in their own countries, quality Western foreign news outlets broadcasting quality information to all parts of the world, thus countering and juxtaposing disinformation and propaganda with quality information, may be one of the most important instruments in the global information war.

Another key element in making societies and media more resilient against information manipulation is media literacy. Modern, digital media in all its playful forms accelerate, modified, facilitated, amplified and globalized disinformation. And each new media comes with new challenges and specificities concerning the quality and credibility of its content. Without establishing at least a minimum of media education and media literacy one can hardly imagine how societies may catch up or even keep pace with the developments in the digital disinformation domain. Without media literacy resilience against disinformation may not be possible. One example of specific media literacy initiatives designed to “vaccinate” or sensitise readers and viewers against mis- and disinformation are video games designed to explain and demonstrate how and why disinformation works. Studies have shown that games such as “Bad Media” and “Harmony Square” had a positive effect on educating their players about how disinformation works and making them less susceptible to false information. “Vaccinating” readers with serious news as a means to reaching the same effects – an approached that is actually quite old – showed, on the contrary, only mixed results.42

Almost the same is true for general education of the population. While it may seem like a platitude, recent studies have again suggested that education and pre-existing knowledge make people less susceptible to disinformation.43And since disinformation may touch on any field of knowledge and topic, a broad and firm general education can help to make populations more resilient against disinformation.

Trust building measures. Public mistrust against politicians, authorities and the media is a major factor that makes disinformation successful. Such mistrust a major problem in most societies in Southeast Europe and has deep historical roots in the mistrust against the Ottoman Empire, corrupt officials and Communist authorities and media. This most probably has also played a crucial role for significant parts of the population during the Covid-19 pandemic: On the one hand, public information repeating WHO information about the virus was often deemed “state propaganda”, while conspiracy theories, on the other hand, found fertile ground and were often broadcasted even by serious news outlets. Building trust is hence a major task, for politicians, media and journalists in the region. This may take the form of a professionalisation of political communication as well as the establishment of (and adherence to) high standards of journalism. Yet, as all authors in this volume point out, such measures are either rare, unsuccessful or simply too isolated as compared to massive political propaganda and bad journalism in Southeast Europe.

Development and dissemination of own narratives. With the Russian war against Ukraine and the return of Cold War-style confrontation and political propaganda, focusing on Russian narratives and disinformation will most probably not be enough. To convince and “inoculate” domestic and foreign audiences against malicious information warfare, propaganda and disinformation, positive narratives about (inclusive) identities, values, beliefs and policy goals are strongly needed. Such narratives might make populations more resilient against harmful disinformation trying to sow discontent, exploiting weaknesses and cleavages. Without such a (Western, European and national) narrative, efforts to counter e.g. Russian or Chinese propaganda will only be partly successful. The dire need for such positive narratives about Europe and its role in the world is particularly strongly felt in the countries of Southeast Europe, where EU aspirations had been high for more than a decade and where strong feelings of disappointment have spread in recent years (e.g. in North Macedonia).

However, all of these approaches and countermeasures come with specific problems and challenges: For example, while there is almost no alternative to debunking at least some disinformation, both debunking and fact-checking are “reactionary” responses to disinformation, i.e. they are always belated and bound to reach a smaller audience than the original disinformation. In other cases, debunking and fact-checking (or even simple reporting) may significantly increase the spread and amplify disinformation. And very often it is almost impossible to judge beforehand which of these risks of either not engaging at all or a possible amplification of disinformation is the lesser evil.44 Another problem of debunking and fact-checking is that both are rational tools, appealing to reason, common sense, knowledge and fact-based judgement. However, disinformation and propaganda very often play on and with the irrational —a with emotions, feelings, moods, trends, fears and desires. Hence, strictly rational approaches to counter disinformation may have problems reaching the same audience and meeting its expectations.45

Another problem, e.g., for a strict security policy and counterintelligence approaches to disinformation, is the “attribution problem” of disinformation. As mentioned above, digital disinformation, like cyberattacks, is often very hard or even impossible to attribute with 100% certainty to an author, origin or source. The secrecy of clandestine disinformation thus impedes efforts to investigate and prosecute it.

Censoring disinformation, either by automated deletion and flagging of content, by banning certain news outlets altogether and by passing “anti-fake news laws” or “anti-disinformation laws” also faces serious problems: defining what is to be censored as disinformation may open the door for unscrupulous lawmakers to utilize the fight against disinformation for their own purposes. Defining what disinformation is, may led the path to “Truth Ministries” claiming an ultimate power to decide what is true or not, thus infringing with basic democratic principles. This was, for example, the main reason the EU for years did not decide to censor even the worst Russian propaganda outlets and why Turkey’s anti-disinformation law of 2022, making the spread of false or misleading information about public health, internal or external security a punishable crime, was so contested.46 Making disinformation illegal by law may create opportunities for unscrupulous politicians and officials to exert their own version of political censorship. Even with automated IT responses, such as automated deletion, these problems cannot be solved entirely: artificial intelligence software too needs to have a human-induced basic notion of what disinformation is and is thus not free from human flaws or influence. In other words: artificial intelligence does not necessarily have an easier time recognizing disinformation. Incidents of automated deletion of satirical content mistaken for disinformation by algorithms demonstrate ostensibly that while software may be better at recognizing deep fake images, it may as well have a harder time to draw a line between human humour and disinformation.

How Successful is Disinformation and what Does that Mean for Countermeasures and Resilience?

Even after decades of analysing disinformation, there is still no definitive answer on how to measure its “success” (or better: damage) and effectiveness. Measuring the success or even the effects of disinformation has always been difficult as there is no clear-cut toolset or methodology on how to determine what “success” means and how to measure it. The Soviet secret service KGB, for example, would rate its disinformation efforts a success if their planted pieces of disinformation: (a) were picked up by any other than the original source; and (b) by the quantity of citations or reprints.47 As insider accounts revealed, the infamous Russian troll factory “Internet Research Agency (IRA)” also followed this pattern and rate its success according to the number of posts, profiles, tweets, followers or reposts their original disinformation pieces received. Yet, as for example research into the influence of the IRA’s activities on the 2016 US-presidential elections showed, only 8,4% of all IRA online activity during the time of the election campaign was related to the election and the bulk of all IRA output was: (a) devoted to audience-building; and (b) stayed within its own echo chambers.48 Was that successful disinformation? Probably not.

Any assessment of the “success” of disinformation needs to keep in mind that the original purpose of disinformation is not mere quantity, but also the quality of influence it achieves. And here, the balance sheet of disinformation quite patchy. Just like modern digital disinformation, a lot of Cold War KGB disinformation stayed within its own echo chambers and was repeated only by media that were on their side all along. It seems like even the ludicrous increase in quantity of disinformation in the digital age does not necessarily equal an increase in quality, effect or effectiveness. Disinformation in the digital era, as one scholar put it, has become “more active, but less measured”49.

Determining what “successful disinformation” is and how effective disinformation it is, is of the utmost importance with regard to countermeasures and resilience. Disinformation, just like any other form of malign, bad or manipulative information, has always been with us. Yet, it is: (a) the increase of quantity of disinformation in the digital age; and (b) the increase in quality, that is actual influence and real-life consequences of disinformation campaigns in recent years, that are troublesome. Countering the quantity of disinformation is something that may easily be achieved by the aforementioned “negative countermeasures”, such as automated deletion, deep-fake recognition and censorship. It needs to be clearly stated, however, that these measures may work to reduce the quantity of disinformation, but will neither make disinformation as a whole go away, neither solve the quality issue, i.e. the actual amount of influence achieved. Yet, the quality of disinformation and its impact on attitudes and beliefs, electoral behaviour, etc. is a lot harder to both measure and counter. Here, the aforementioned “positive countermeasures”, such as quality journalism, media literacy and general education, may provide a solution.

We need to be clear that disinformation will neither vanish, nor will there be a flawless or singular “catch-all”-approach to deal with it. So far, media, political and academic discourse have focused on such approaches more or less in isolation and individually or have placed high hopes on technological solutions alone. Yet, the complexity of disinformation, its mechanisms, forms, content, its necessary predispositions as well as the complicated metrics of its “success” suggest that an integrative approach, that is a combination of all countermeasures promises the best results for a resilient society.

Therefore, the editors of this volume decided to include all of the above-mentioned approaches to fight disinformation and ask the question how (and if at all) they are being implemented in the countries of Southeast Europe. Yet, the results are somewhat disheartening. Most case studies clearly point to a lack of media literacy, general education and malicious intent of domestic

political actors as main factors for the far-reaching effects of disinformation in Southeast Europe. Fact-checking initiatives are the most common tool against disinformation, yet in all countries these initiatives are rather small, understaffed, underfinanced and nowhere near reaching a broad audience.

Far-reaching problems in the media sector, strong foreign influence, poor journalism and above all the lack of political will and initiative to effective fight (and not exploit) disinformation are, on the other hand, important factors for the increase of disinformation during the Covid-19-pandemic and the war in Ukraine. Yet, there are also signs of hope on the horizon. For example, the“Registry of Professional Online Media” published by the Council of Media Ethics of North Macedonia to provide the public with a list of professional media outlets (as compared to mere portals and self-created sites). In Kosovo, to give another example, media literacy has recently been made an elective subject in high-school education. Despite several problems with the organisation and execution of media education, Kosovo is thus one of the first countries in Europe trying to put efforts of improving media literacy of pupils into action.

The case of Albania

By Rrapo Zguri

Introduction

Disinformation is a global challenge that has created problems in both established and new democracies. It has also been used as an instrument of geopolitical influence. Election campaigns in different countries have often been damaged by disinformation, creating a veil of doubt in the liberal-democratic system itself. The manipulation of information has also undermined social and political solidarity in response to global challenges, such as the recent COVID-19 pandemic.

In few places is this threat more acute than in the Western Balkans –as a February 2021 European Parliament Report notes: “As a theatre of geopolitical dispute and sharply polarized politics, characterized by weak governance and fragile civil societies, the Western Balkans are a uniquely attractive target for both foreign and domestic actors seeking to alter, undermine or delegitimize the outcomes of democratic processes. Disinformation affects many areas of social and political life in the Western Balkans, but still, it is not the case that disinformation is the cause of democratic breakdown. Rather, it is the lack of commitment to democratic governance by domestic political actors that opens the door to the productive use of disinformation as a tool of political competition.”50

Within this broad context, disinformation and manipulation of information in the Albanian public sphere have enjoyed considerable success. The delay in the maturation process of democracy and the gaps in democratic culture, associated with the abuse of new communication technologies, as well as the efforts of third parties to penetrate the country, have been among the main factors that have influenced the presence and spread of disinformation in Albania.

The aim of this article is to offer an overview and summary of definitions, contents and narratives as well as countermeasures against disinformation in Albania. The collection of empirical data for the needs of this study is based on online keyword research as well as on the monitoring of some specific case studies. The search is limited to the last 5 years.

Terminology and Definitions of Disinformation in Albania

Manipulation of information is not a new development for Albania. During the nearly 50-year period of totalitarianism, the population was exposed to an unprecedented wave of disinformation and propaganda aimed at casting the communist regime in a positive light and presenting it as superior to liberal-democratic systems. But disinformation has been present even during the years of the post-communist transition, its reach increasing in lockstep with the proliferation of new information and communication technologies.

The term “disinformation” itself is a relatively new addition to the Albanian language. It gained currency after the fall of Communism, when Albanian scholarly studies in the field of mass communication and information began and when pluralist mass media first emerged. In Albanian, the term is more part of the academic and scientific lexicon, but it is increasingly finding a place in the political lexicon and in the media as well as in interpersonal communication. Traditionally, to express the concept of disinformation

in the Albanian language, the term “keqinformimi” has been used, which literally translates to “mal-information” in English. Although they have already entered the Albanian language, the corresponding words for “disinformation” (Albanian: dezinformim) and “misinformation” (Albanian: ç’informim) are missing in the Dictionary of the Albanian Language.51 Depending on the context, the term “keqinformimi” in Albanian expresses and represents both the meanings of the word “mal-information” and those of the words “dis-information” and “mis-information”, thus serving as a polysemantic term.

In recent years, and especially after the translation into Albanian of Information disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making a Council of Europe publication authored by Claire Wardle and Hossein Derakhshan,52 Albania has begun to differentiate: “dezinformim” is used to mean “disinformation”, “ç’informim” is used for “misinformation” and “keqinformim” for “malinformation”. The nuances of meaning expressed by these terms parallel those of their English counterparts, as follows:

- Dezinformimi (English: Disinformation) - Information that is false and deliberately created to harm a person, social group, organization or country.

- Ç’informimi (English: Misinformation) - Information that is false, but not created with the intention of causing harm.

- Keqinformimi (English: Malinformation) - Information that is based on reality, used to inflict harm on a person, organization or country.

Meanwhile, unfortunately, there is still no definition of disinformation proposed by Albanian authors, institutions and public discourse. For the purposes of this study, the basic definition is the one that defines disinformation as “false, inaccurate, decontextualized and misleading information COVERTLY designed, presented and DELIBERATLY promoted and spread to manipulate and exert political, financial or other influence”.53

In some studies conducted by Albanian authors, the term “disinformation” is also used in association with, or instead of, the word “propaganda”, meaning “misleading information”, which is also a feature and part of propaganda information.

In normative or legal documents in the Albanian language, for example, the code of ethics of the media, the criminal code or the civil code, disinformation has not yet been established as a separate term, notion and practice. Thus, the Code of Ethics of Albanian Media has three paragraphs dealing with disinformation-related issues, as follows:

Media should not mislead the public, and they should clearly indicate where manipulated texts, documents, images and sounds have been used.

Media should not distort or misuse statements made in a specific context. Media should not publish any image, audio, or visual arrangements that distort the ideas or facts of the source, with the exception of caricatures, cartoons or comic plots.54

Note that the Code of Ethics addresses the problems related to disinformation but does not mention or distinguish it as a term or as a category of information manipulation. In the Criminal Code issues related to disinformation are touched upon in Article 120, entitled “Libel”, as follows:

“Intentional dissemination of statements, and any other pieces of information, with the knowledge that they are false, affect a person’s honour and dignity, shall constitute criminal misdemeanor […”]55

Apparently, the intersection of meanings between the various terms related to the information disorder create a situation in which, on the one hand, similar but distinct terms are used interchangeably and, on the other hand, older terms are preferred to newer terms not only in the academic literature but also in normative and legal texts.

The Target Group(s) - Audience and Perspective of Disinformation in Albania

Being spread mainly through the media, disinformation has called into question the public’s trust in them. An opinion poll conducted in Albania on February 2021 by IPSOS Strategic Marketing with a sample of 1010 adult respondents and followed by a focus group of six journalists and editors from various media outlets, revealed that spreading disinformation is the primary reason for distrust in media.56

Source: IPSOS, 2021

When asked why they distrust media outlets, the public seemed to have a concrete answer: almost half of them (48%) cited “the spread of disinformation” as their main reason.57

The level of public trust in the media is determined to a large extent by the level of fulfilment of its public mission. Especially when the media fails to be, even partially, representative and a servant of the public interest, a crisis of trust begins to form. A fundamental question that could be asked in this context is: How much has the media in Albania served democracy and the democratization of the country?

A survey undertaken by the Albanian Media Institute (AMI)58 in 2019 reveals that the vast majority of the Albanian public (70%) agrees that the media environment is of great importance for a country’s democracy. But even though they recognized the media in general as having a very important role in relation to democracy, only about half of the respondents (48.6%) said that in fact the Albanian media have been serving democracy and the public interest to some degree. Also, only about half of the public (46.4%) said that the media have to some degree being helping the fight against corruption, thus exposing a significant deficiency in this aspect of the media’s public mission. This reflects the deficits of the Albanian media in relation to democracy and is evidence of a limited role in its development and protection.

Besides damaging the media’s role and reputation, disinformation has also influenced the journalistic profession and the production of news. One of the main impacts of disinformation is on journalists’ sourcing techniques. In surveys and interviews with journalists most of the journalists queried declared that the current news environment made them increasingly careful about their sources in general. They describe the motivation to double-check sources as both a reaction to disinformation and as a way to protect themselves from accusations or from being labelled as “fake news.”59

Another downstream effect is increasing distrust of sources and the accompanying increased time spent validating sources. Many journalists report that their job now takes more time due to increased information and increased awareness of the circulation of false information. Sources also seem to be more distrustful of members of the media.

A major effect outlined by journalists concerning the production of news is the increased transparency regarding the journalistic process. Many mention an ongoing push in the industry to more clearly label opinion and news articles to avoid readers conflating them and form heightened perceptions of journalistic bias that can foster increased distrust.60

In addition to its effect on journalism and journalistic practices, disinformation has been posing great challenges for audiences and media users too. “Audiences may be misled as to the authenticity of the purported facts of the matter (e.g., ‘vaccines cause autism’) or the source of the material (e.g., ‘reputable scientists say vaccines cause autism’), and factual material may be taken out of context in order to provoke a particular response,” according to a European Parliament report.

“Even the nature of the distribution channel itself may be a lie (such as the recently uncovered ‘Peace Data’ website). In all cases, however, the goal is the same – ‘to manipulate a target population by affecting its beliefs, attitudes, or preferences in order to obtain behaviour compliant with political goals.’”61

The outlook becomes even clearer if we take into account the low level of media literacy among the Albanian public. It is well known that the lower the level of knowledge that the public has about media and news, the higher the risk of disinformation and manipulation through the media.62 The “Media Literacy 2021” index ranks Albania 33rd among European countries, outdoing only Bosnia Herzegovina and North Macedonia. This proves once again that Albanian citizens continue to be among the most vulnerable citizens in Europe when it comes to fake news and disinformation. Even the fact that the percentage of people in Albania who believed in conspiracy theories about Covid-19 was the highest in the Balkan region63 shows the problems that exist in the general public regarding the understanding of the messages conveyed by the media. The situation calls for improvements in media literacy among the general public, starting from students to the elderly. The continuing delays initiatives for the implementation and dissemination of media literacy in the country have experienced are deepening the risk of informational manipulation of the public.

The spread of disinformation has led to increased control efforts as well as to attacks on the media by the government and by politicians. The last few years have seen a definite uptick in Albanian political leadership denigrating the media in their speeches. The “cauldron” metaphor the Albanian prime minister uses in his arguments against some media outlets and certain actors is notable in this context.64 This sort of language on the one hand seems to exert increased pressure on critical voices in the media; on the other hand

it has tightened political control over the media.65 It has also resulted in a decrease of trust in the media. The “fake news” phenomenon meanwhile has encouraged politicians, business executives, and others in the public eye to label unfavourable investigations as “fake” and has emboldened their attacks on the credibility of critical reporters. This has led to an environment in which harassment of journalists is increasingly accepted.66

Narratives, Case Studies and Examples of Disinformation in Albania

Disinformation in Albania takes a range of shapes and forms, but, as our research reveals, the most prominent types of it are: (1) Domestic political disinformation; (2) Crisis disinformation (such as the context of Covid-19); (3) Disinformation coming from third-state actors; and clickbait disinformation.

(A) Domestic Political Disinformation

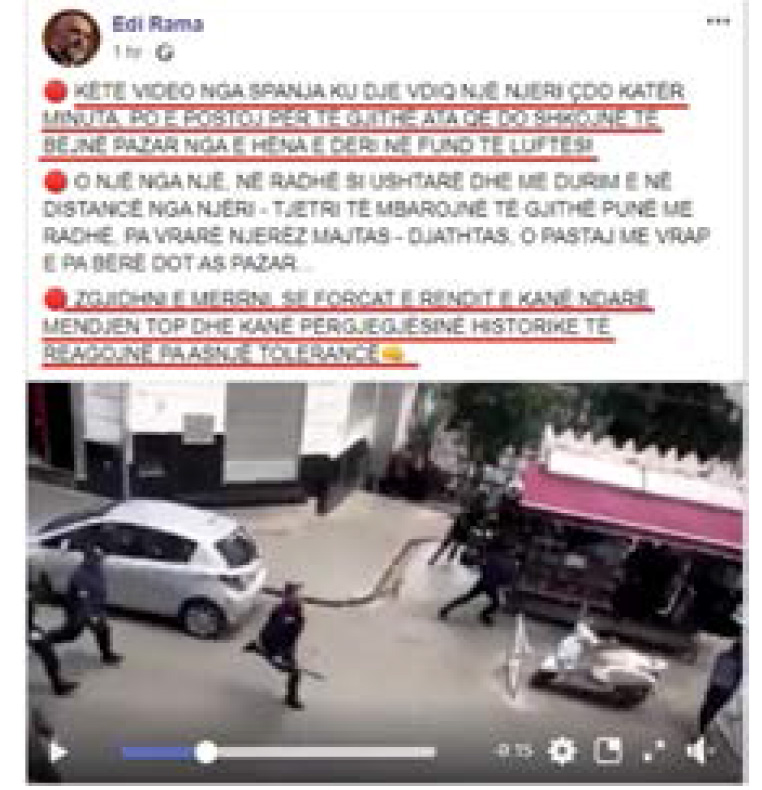

The most widely used type of disinformation in Albania is the one that is produced and disseminated for political purposes by domestic actors. Numerous politicians across the spectrum have used disinformation to damage the image of their political rivals, to gain visibility or to put their own activities in a positive light. In March 2020, when the Covid-19 pandemic had just started to spread in the country, the Albanian government took very strict measures to limit the movements of citizens by imposing a kind of curfew in residential areas. These extraordinary measures were heavily criticized by the media and sparked public outrage. In order to justify these measures, the Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama published a video on Facebook that showed, he claimed, the Spanish police violently dispersing a citizen’s protest against similar restrictive measures. Research by the Albanian fact-checking platform Factoje revealed that the violent footage was taken during the dispersal by the police of a citizens’ protest in Algeria.67

Screen-shot of the Albanian Prime Minister’s post

On the other side and at about the same time, the leader of the opposition, Sali Berisha, posted a video of doctors in a hospital, claiming that this was how the government, and the Albanian health system, were being prepared to cope with the pandemic. It turned out the footage had been filmed in Iran and had nothing to do with Covid-19.68

Being part of a polarised environment, political actors in Albania have used their satellite media to publish manipulated information, often coming from manipulated sources. Standard.al, a major online news outlet linked to the opposition Democratic Party, published a report that alleged Rama’s government had allowed the import of 1300 tons of toxic waste that had disappeared from Italy in early 2017.69 The source of this false information was an anonymous online portal based in Italy that disappeared as soon as questions started being asked.

In other cases, pictures from different contexts or different times are used to mislead the public and to create wrong perceptions about actual events. Research also identified several cases of photos that had been staged, that had been doctored, or that distorted facts through manipulative shooting angles. Last year, for example, a pro-government media outlet tried to downplay participation in a protest organized by the opposition through drone footage taken from a misleadingly high angle. Pro-opposition media tried to exaggerate participation in the same protest through shooting from a low angle. Shooting angle, viewpoint and perspective, we can see, can be used as tools of manipulation, as tools to add or subtract “truthiness”.

However, even though it is the most widespread type, domestic political disinformation in Albania has never taken the form of a coordinated and sustained campaign. Examples are generally opportunistic in nature, and the goals are shallow.70

(B) Crisis Disinformation and Covid-19

The various crises the country has been facing have also served to inspire disinformation. A typical example is that of the Covid-19 pandemic. The most widespread type of disinformation related to the pandemic in Albania has been the one involving conspiracy theories. According to a BIEPAG survey, Albania was the country with the highest number of supporters of conspiracy theories in the Western Balkans during the Corona crisis. Every individual false narrative, no matter how incoherent, had a greater number of supporters in Albania than elsewhere. The number Albanians who believed at least one conspiracy theory reached 59.4% of the population.71

The most important narratives of disinformation related to pandemic in Albania were the following:

- COVID-19 was created in and emerged from a Chinese laboratory in Wuhan.72

- The Corona virus was created by the White Brotherhood or by the “Deep State” to reduce the world’s population.73

- The Corona virus was created by Bill Gates, who wants to use vaccines to install microchips in people, which will allow him to exercise global control.74

- The aim of installing of 5G mobile networks was to speed up the spread of the virus.75

- COVID-19 is either a hoax or a harmless ailment similar to the common flu, exaggerated by governments or by special groups for nefarious secret purposes.

In addition to conspiracy theories, disinformation during the pandemic in Albania also appeared in the form of made-up news, for example reports about miracle drugs that can cure Covid-1976 or about the healing effect of various herbal remedies.77

It appears that the main actors that have contributed to the spread of conspiracy theories are different media outlets as well as some controversial individuals who used the opportunity to promote these theories. In contrast to many countries where the main channels of spreading these types of disinformation were social networks and online media, in Albania, unfortunately, the mainstream media were also involved in this process. As a BIRN report emphasis, the country’s leading television channels rolled out the red carpet for conspiracy theories against vaccines.78 Typical here is the case of Top Channel, which for more than two years has offered screen time to Alfred Cako, a well-known conspiracy theorist. Cako appears on a talk show every Sunday and freely promotes his disinformation theories.79

According to a report issued by the State Intelligence Service of Albania (SHISH), meanwhile, the Corona crisis was also used by third players to exert their influence in the country. Without naming any specific country or actor, the service noted that “non-Western global actors have exploited the situation caused by COVID-19 for their geostrategic goals, strengthening their position as international actors, disrupting EU/NATO and international cohesion, and supporting each other’s narratives in the information environment according to their goals. Also, they used a wide spectrum of hybrid tools to undertake information operations throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, such as: undertaking media campaigns, circulating fake news, promoting and spreading conspiracy theories through the media and social networks, engaging the services of intelligence and state and non-state cyber actors.”80

(C) Disinformation from Third-State Actors

“In the early 2000s, everything indicated that the countries of the Western Balkans were destined to integrate into the common European project as soon as possible,” according to the Albanian analyst Liridon Lika. “But the enlargement process has slowed down due to delays in the implementation of reforms as well as political and economic problems between Western Balkan countries, coupled by an ‘enlargement fatigue’ within the EU. In the context of this slowdown in EU accessions, new emerging powers tried to fill that void, such as Russia, China and Turkey, and extend their influence in the region.”81

The main lines of disinformation discourse coming from third parties are those that aim to damage the image and reputation of the EU, the USA and NATO in the countries of the Western Balkans and in Albania. An online comment on the Nagorno-Karabakh crisis, for example, alleges a weakening and declining role of the EU in the region and the world. In the case of Nagorno-Karabakh “…the biggest loser is in fact the European Union… The EU has again managed, in a spectacular way, to fail to play the role of a relevant actor and peacemaker on its eastern suburbs,” according to a comment with the headline “Why the biggest loser in Nagorno-Karabakh is the European Union.”82

Another story goes even further, saying that “over the last five years, the OSCE or even the EU and the US have not managed to successfully negotiate on any conflict, revealing significant weaknesses on their part. The US and the EU have also failed to negotiate a solution in a region very close to their area of influence, like Kosovo, while Ukraine is still in a limbo. Two more states have been added to the list of countries in crisis, Libya and now Belarus, a country in a twilight situation that defies any definitions, where stability is determined by actors like Russia.”83 The minimization of relations and official communication between Albania and Russia has resulted in the latter having a negligible influence in Albania. The few articles in Albanian media that still seek to promote some kind of pro-Russian agenda are either driven by nostalgia for the Soviet Union or appear in media influenced or financed by foreign actors.

One Albanian news site claimed, for example, that “Russia has been coherent in its stance on Kosovo, adhering to UN Resolution 1244. Likewise, it has been coherent since the beginning of the dialogue between Pristina and Belgrade, stating that Russia itself would support any agreement reached between them, and that it would behave as if ‘more Serbian than the Serbs themselves.’ Unlike the Albanians who have sometimes shown that they are more ‘American than the Americans themselves,’ or as we commonly used to say ‘more catholic than the Pope himself’.”84 This sort of reporting, in addition to consistently serving Russian interests, spreads disinformation when it comes to Russia’s stance towards Kosovo, and sneaks denigrating rhetoric about Albanians in between the lines for good measure.85

Anti-EU rhetoric an article published in online media turns to history to support their claims, arguing that “those who tore us to pieces in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century were the same countries that now constitute

the core of the EU, plus England.”86 This quote was pulled from a piece of commentary that praised the “historic contributions” of Russia to Albanian statehood, which in fact is clear disinformation.