Author: Dr. Heinz Gärtner

Austrian Institute for International Affairs, Vienna, Austria

ABSTRACT

EU enlargement cannot be halted or indefinitely postponed and the question is: what will be the key concept utilized in the enlargement policy.

It will certainly be a combination of previous element; that is, the candidate countries need markets, democratization, peace, and the opportunity to become a part of post-bipolar Europe. In order to draft their agendas, southeastern European candidates must use already existing EU processes. Security is one such process and CFSP and ESDP are its pillars. The Fiera Council set a goal of a common police force of 5000 men by the year 2003. Aspiring countries must take concrete steps to build confidence, merge resources and knowledge, and harmonize doctrines and assets. Each country must also share information on crime cartels, transport routes, and potential threats in order to create stability and regional confidence.

It will certainly be a combination of previous element; that is, the candidate countries need markets, democratization, peace, and the opportunity to become a part of post-bipolar Europe. In order to draft their agendas, southeastern European candidates must use already existing EU processes. Security is one such process and CFSP and ESDP are its pillars. The Fiera Council set a goal of a common police force of 5000 men by the year 2003. Aspiring countries must take concrete steps to build confidence, merge resources and knowledge, and harmonize doctrines and assets. Each country must also share information on crime cartels, transport routes, and potential threats in order to create stability and regional confidence.

Recent developments in the Common European Policy on Security and Defense

The end of the Cold War compels a reappraisal of national security policies for a continent undergoing major structural changes. Crisis management is the paradigm for the new system of international security, one that faces more threats than during the Cold War. The operational thrust of NATO and the Western European Union (WEU) is now focused on crisis control.

Whether members of an alliance or the Partnership for Peace (PfP), states will participate in crisis management, peacekeeping, humanitarian action, and peace-enforcement operations. All EU members could participate in these activities in the framework of the "Petersberg tasks/' but they would decide. Also, the tasks of the allied and non-allied states would be different.

The old argument that alliances do not survive without clear and continuing threats has used for examples those coalitions against Napoleon, the First World War entente against Germany, and the later league against Hitler. Analysts decided, therefore, that after the end of the East-West conflict, "NATO's days are not numbered, but its years are." But NATO is still active and robust long after the end of the Cold War. Question: How does NATO survive without serious, active opposition?

The answer lies in NATO's capacity for change. Preparing for a coalition war is no longer a first concern; its focus now is on crisis management and response, peace-keeping, humanitarian action, and peace-enforcement. Also the lines of the NATO "area" (Art. VI) are changing; the NATO-led operations in Bosnia and Kosovo/Yugoslavia are a case in point, NATO now focuses on single missions of collective defense as during the Cold War.

NATO's challenges now include international terrorism, the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, the disruption of Gulf oil supplies, and instability along NATO's southern and eastern flanks. These challenges do not represent a direct threat to NATO territory; for NATO's future is no longer in territorial defense but in crisis management. However, NATO is still capable of mobilizing the forces needed to defend against threats in central Europe, but maybe not as capable of supporting forces trained for crisis management or peace keeping operations.'

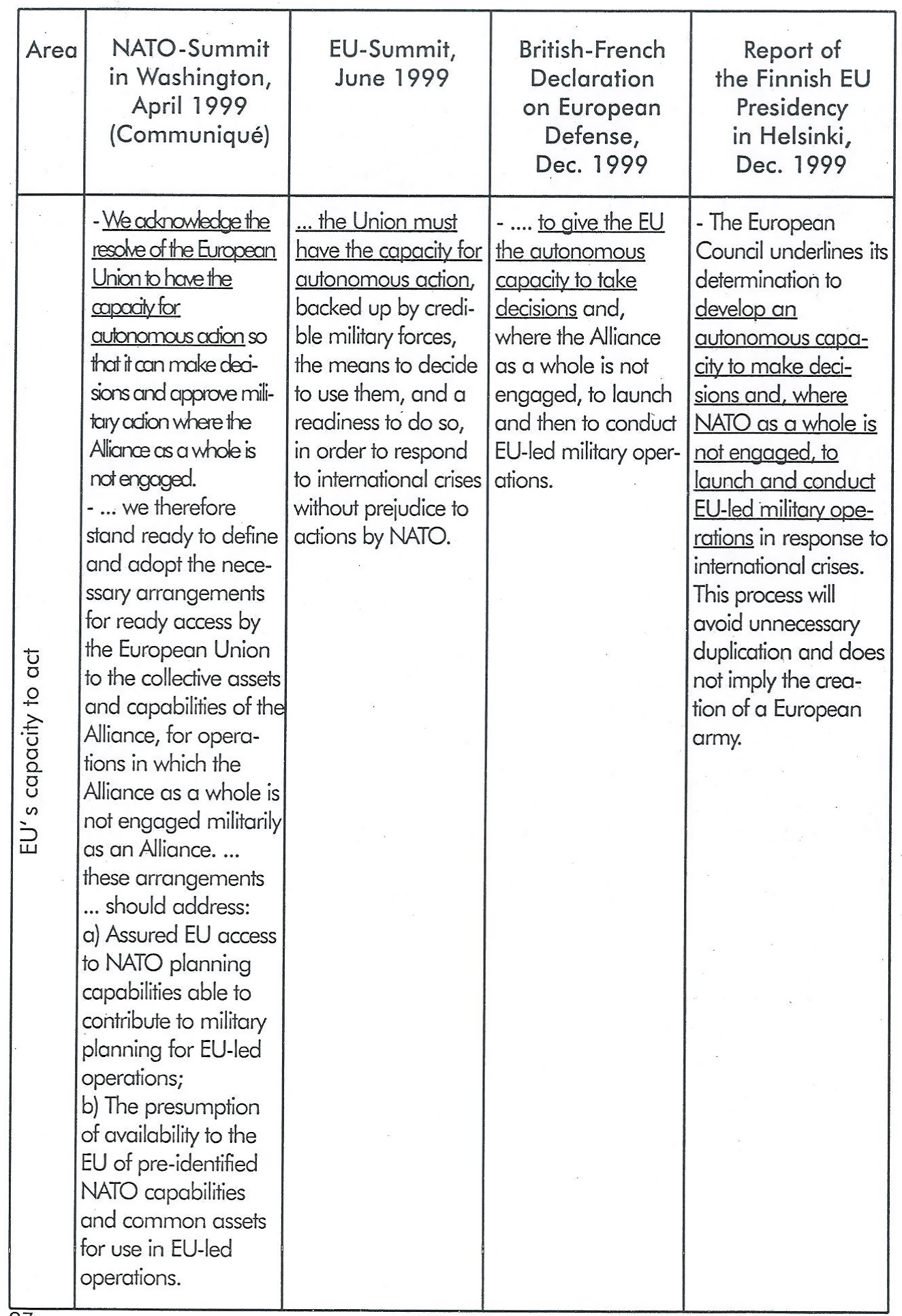

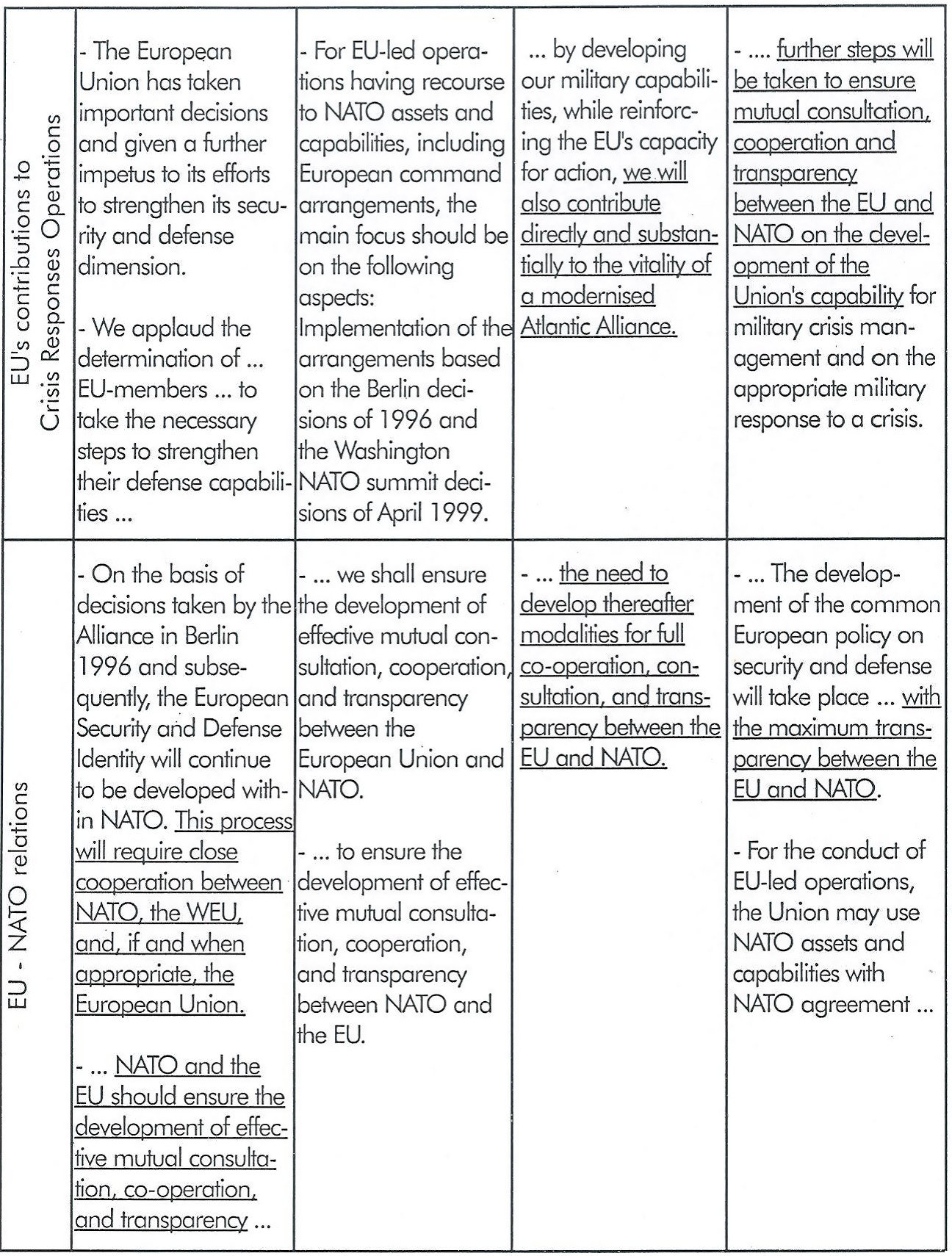

The Washington Summit Communique (April 19992) and NATO's new Strategic Concept3 stress that NATO will be larger, more capable, and more flexible. NATO will still be committed to collective defense, but will also be engaged in conflict prevention, crisis management, and crisis-response operations.

The Partnership for Peace (PfP) program has been designed according to the new requirements. More than merely a new form of cooperation, NATO's new instruments and tasks will blur the differences between members and non-members (i.e. partners). PfP/EAPC offers most of the benefits of NATO except the collective security guarantee articulated in Art. V of the Washington Treaty. As Perry, the former U. S. Defense Minister, foresaw during a meeting (December 1996) of NATO Defense Ministers in Bergen, "The difference between membership and non-membership in NATO would be paper-thin." In some cases non-NATO members may play a more important role in the new operations than NATO members, as NATO's focus gradually shifts from Art. V missions (territorial defense) to non- Art. V missions (crisis management).4 Washington believes that PfP/EAPC will draw Partners much closer to NATO in the areas of peace operations, humanitarian intervention, and crisis management. Non-NATO states could participate in missions while retaining their current defense profile.

The Treaty of Amsterdam of the European Union (June 1997) included the "Petersberg tasks." It states in Art. 17 that "the Union can avail itself of the WEU to elaborate and implement decisions of the EU on the tasks referred to...." These are "humanitarian and rescue tasks, peace-keeping tasks, and tasks of combat forces in crisis management, including peacemaking." The Treaty did not merge the WEU and EU. It simply states that "the WEU is an integral part of the development of the EU. The EU shall ... foster closer institutional relations with the WEU with a view to the possibility of the integration of the WEU into the Union..." The precondition is a European Council decision and its adaptation of such a decision by the Member States only "in accordance with their respective constitutional requirements." The Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) of the EU will, according to the treaty, "include all questions relating to the security of the Union, including the progressive framing of a common defense policy ... which might in time lead to a common defense, should the European Council so decide." Such a decision has to be "in accordance with [the Member States'] respective constitutional requirements."

Based originally on a Swedish-Finnish proposal, the Treaty allows "all (EU) Member States contributing to the tasks in question to participate fully on an equal footing in planning and decision-taking in the WEU." Membership in the WEU, therefore, is not necessary to participate in the "Petersberg" tasks.6 The European institutions, WEU and EU, will limit their defense activity to the creation of a separate force for crisis management. The federal approach still plans to merge the EU and WEU; Art. V (collective defense and binding security guar-antees of the WEU treaty) should be incorporated into the EU. This would lead to the creation of a new military alliance.7 But a radical development is unlikely and not a present option. The EU after Amsterdam focused on the "Petersberg missions," including crisis management, peace-keeping, humanitarian action, and peace-enforcement, rather than Art. V operations (collective defense and security guarantees).

The European Council in Helsinki (December 1 999) adopted the two Presidency progress reports on developing the Union's military and non-military crisis management capability as part of a strengthened common European policy on security and defense. The Finnish presidency8 of the EU has given priority to the mandate of the Cologne European Council to strengthen the European policy on security and defense in the area of military and non military-crisis management. The document stresses that the Atlantic Alliance remains the foundation of the collective defense of its members. The common European headline goal is a military capability (based on, a British and French proposal) consisting of a European rapid reaction force of up to 60/000 troops deployable within 60 days and capable of operating without outside help.

The European Council is determined to develop the autonomous capacity (where NATO "as a whole is not engaged") to launch and conduct EU-led military operations in response to international crises. This ability avoids unnecessary duplication, but does not imply the creation of a European army.

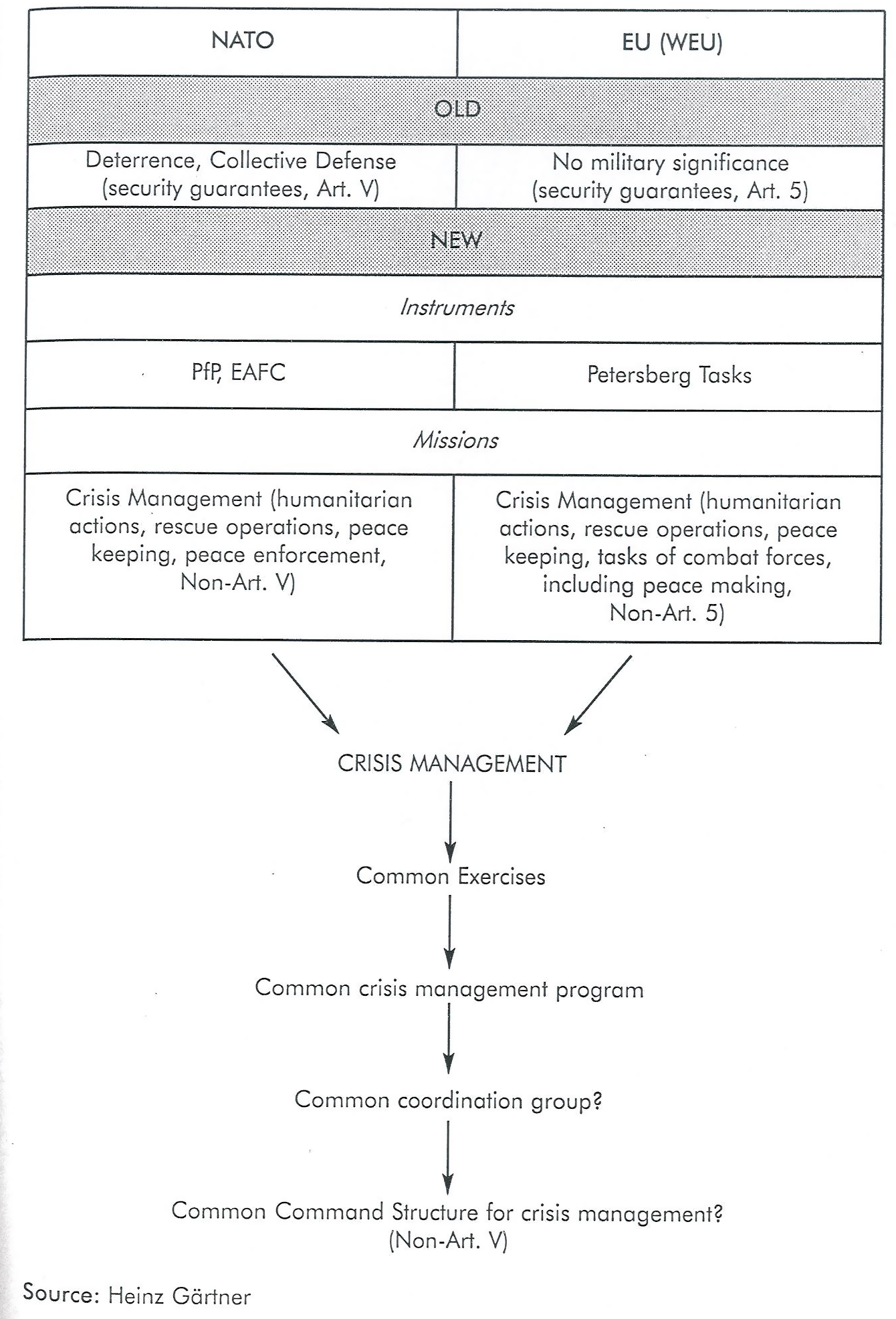

We have bifurcation in NATO and EU (WEU): that is, both collective defense and crisis management. There is also duplication of missions: the Amsterdam Treaty with the inclusion of the "Petersberg" tasks here and the new NATO with PfP and EAPC there. Add to these crisis management here and crisis management there, non-Art. V of the WEU here and non-Art. V of NATO there. To avoid this overlapping, it would be more logical to merge the non-Art. V missions and combine "Petersberg" and PfP instead of to merge WEU and EU. Europe and America face identical challenges: the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, disruption of world energy resources, international terrorism, transnational organised crime, and ethnic conflicts. All affect US and European interests.

A new command structure (based on NATO and WEU) could be created to deal only with non-Art. V operations. Such a command structure would be based on both NATO and WEU. A political "coordination group" would plan the crisis management tasks. The command would alternate between America and Europe. Member states would assign trained forces, based on the Combined Joint Task Forces (CJTF) that focus on non-Art. V operations. The CJTF has become an agent in NATO crisis management, but still maintains a European identity.

A first task could be a program for joint NATO-WEU crisis management. The first major crisis management exercise (CMX 2000) followed a "Petersberg" mission scenario (peace support mission) and made use of NATO assets and capabilities. It was designed to test WEU and appropriate NATO crisis management mechanisms and procedures, as well as the communication apparatus between WEU and NATO (i.e., the interaction between each organization's headquarters and WEU/NATO nations.) More exercises will follow.

Table 1: Key Areas of EU and NATO

Source: Heinz Gartner. The author received important suggestions from Johann Pucher.

.

The advantages of a new Command Structure

- The old part of NATO and WEU - the collective defense -would remain intact. Traditional functions and obligations would continue. Also PfP could demonstrate that it has a role and a rationale and is not just a waiting room for membership.

- NATO Secretary General, Robertson10 (the WEU Ministerial, Luxembourg, November 23, 1999) called for complementary efforts by European institutions to achieve the new command structure's three principles: improvement in European defense capabilities; inclusiveness and transparency for all Allies; and the indivisibility of Trans-Atlantic security.

- Non-members of NATO and WEU (Austria, Sweden, Finland, Ireland) could participate in the new command structure, for only Art. V commitments are inconsistent with their non-aligned or neutral status. The Gulf War, IFOR/SFOR in Bosnia, and KFOR in Kosovo showed that international coalitions responding to crises in or out of Europe may include non-members. These states should participate in the decision-making process.

- It would also further EU enlargement in the field of securi¬ty by including non-members of the EU that are partici¬pants in PfR For NATO members who are not in the EU (Hungary, Poland, Czech Republic, Turkey, Norway, Iceland), participation is voluntary.

- The new structure would not threaten Russia. It could be included at a later stage.

- Participation by NATO members in the new command structure is optional. Those who decline can still take part in collective defense missions.

A common command structure could obviate the problem of WEU using NATO assets and capabilities for its own interests, a scenario the US wants to avoid. Such operations require a UN or OSCE mandate. A new crisis management command structure would therefore ensure NATO's effectiveness, preserve the Trans-Atlantic link, and develop ESDI.11 The overriding imperative is to put in place a new force that is mission oriented. It also would meet NATO Secretary General Robertson' s three "I’s”: an improvements European Security and Defense; the inclusion of all Allies; and the indivisibility of Allied security. It would also meet former US Foreign Minister Albright's three "D's": no decoupling of European from Trans-Atlantic security commitments; no duplication of defense assets; no discrimination vis-a-vis non EU NATO members.

Notes

1 Dieter Mahncke, "The Role of the USA in Europe: Successful Past but Uncertain Future?" European Foreign Affairs Review, Vol. 4, Issue 3 (Autumn 1999), 353-370, here 364-365.

2 "An Alliance for the 21 st Century," Washington Summit Communique, Issued by the Heads of State and Government participating in the meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Washington, DC on 24th April 1999.

3 The Alliance's Strategic Concept, Approved by the Heads of State and Government participating in the meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Washington DC on 23rd and 24th April 1999.

4 F. Stephen Larrabee, NATO Enlargement and the Post-Madrid Agenda (RAND, Santa Monica: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

5 Stephen J. Blank, "NATO enlargement between rhetoric and realism," International Politics, Vol. 36, No.l, March 1999, 67-88, here 69.

6 Austria presently occupies observer status in the WEU.

7 The WEU-Treaty prohibits such a development, however. Art. IV states that "recognising the undesirability of duplicating the military staffs of NATO, the Council and its Agency will rely on the appropriate military authorities of NATO for information and advice on military matters."

8 The Finnish Presidency, Presidency Report to the Helsinki European Council:

Strengthening of the Common European Policy on Security and Defense: Crisis Management, Helsinki, Dec. 11-12, 1999.

9 David C. Gombert / F. Stephen Larrabee (eds.), America and Europe, A Partnership for a New Era, Cambridge 1997, p. 237.

10 Secretary General's Address at The WEU Ministerial In Luxembourg, 23 November 1999.

11 General Klaus Naumann, "NATO's new military command structure," NATO Review, Spring 1998, No. 1, p. 11.

Table 2: Common CRISIS MANAGEMENT