Hybrid Threats In 21st Century – Theory and Research of The Term In Bosnia And Herzegovina

(Volume 20, br. 1-2, 2019.)

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.20.1-2.9

Autor: Robert Kolobara, PhD, Intelligence and Security Agency of B&H, Bosnia and Herzegovina

This is English language version of the article

https://www.nsf-journal.hr/NSF-Volumes/Focus/id/1270

Abstract

We live in the era of mass technology and global society bombarded by information and now more than ever we need to understand and assess the nature of communication and what it relays. Basis for the use of power and resources distribution has thus changed and it became quite obvious that the new methods of dissemination of messages to great distances, at considerably greater speed, will fundamentally change the nature of human interaction.

In the contemporary world, interest and care for manipulation of public opinion, forming of attitudes and influence on behaviour reached unprecedented levels. Hybrid threats and wars became a first-class security issue of 21st century, and a sign and an indication of the security in the future. This work deals with theory and research of the term hybrid warfare and threats in Bosnia and Herzegovina through a sociological field survey of the population aiming to inductively establish the level of public knowledge on it.

In the contemporary world, interest and care for manipulation of public opinion, forming of attitudes and influence on behaviour reached unprecedented levels. Hybrid threats and wars became a first-class security issue of 21st century, and a sign and an indication of the security in the future. This work deals with theory and research of the term hybrid warfare and threats in Bosnia and Herzegovina through a sociological field survey of the population aiming to inductively establish the level of public knowledge on it.

Keywords: Hybrid threats, hybrid warfare, information operations, security

Introduction

Barnett highlights that during the Cold War, security to the USA and the USSR meant national security from the military and ideological threat by one against the other, while the basic strategy for achieving the security was building and maintaining superiority. In that context, Giacomo Luciani claims that the national security was most commonly defined as the ability to withstand aggression from abroad. Mutimer states that claiming something is a security issue means claiming that it represents the most serious threat possible, existential threat, and if such threat is accepted, it will result in serious political consequences. In the post-Cold War context, perhaps the best definition of security was given by Soroos, who defined security as “people’s conviction that they will continue enjoying the things of utmost importance for their survival and well-being“ (Soroos, 1997, p. 236). Definition of national security according to the last-century discourse was put into question by the new “contemporary” security reference concepts. According to the “new” national security culture of 21st century, the first three positions of the present-day global security threats are taken by the phenomena such as terrorism, hybrid warfare and, what we would call, the state of a failed state. Also, the very current economic issue of sustainable development, having considerable consequences for the national security too, is introduced to the discourse.

Christoper Dent explain how, in the post-Cold War context, (economic) security is focused on the shift from geopolitics to geoeconomics, from the military powers to the economic super-powers, and eventually, from the political-ideological competition to economic competition. Stremlau observed on time: “we are entering an era when foreign policy and national security will increasingly revolve around our commercial interests, and when economic diplomacy will be essential to resolving the great issues of our age“ (Stremlau, 1994, p.18).

Many believe that in the information era, economics and politics are no longer organised in a big, bureaucratic hierarchy, but as a loosely structured horizontal network. Basis for the use of power and resources distribution has thus changed and it became quite obvious that the new methods of dissemination of messages to great distances, at considerably greater speed, will fundamentally change the nature of human interaction.

Two important events marked 2014 as a turning point in the history of international security: Russian interference in the Ukrainian crisis and the rise of the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq. The biggest focal trait and common point of these unrelated events is not necessarily the relative success of political actors (Russia and the Islamic State) in conquering territories, but their success in using the information space through the effective use of new communication opportunities (Friedman, Ofer; Kabernik, Vitaly and Pearce, James C., 2019, p. 1). The Information Revolution, taking place over the last two decades, has finally manifested itself in a way that political actors conduct, interpret and perceive conflicts. The concept of hybrid warfare was one of the first attempts by the professional community to address this rapidly changing character of conflicts, where smart use of new technologies to influence the hearts and minds of the targeted public offers considerably better results than the real action, Friedman said.

Russian strategists and political scientists emphasise two main aspects that characterise the nature of the post-Cold War era confrontations: 1. with a view to crush an opposing nation through gradual erosion of its culture, values, and self-esteem; and 2. emphasis is rather placed on the political, information (propaganda) and economic instruments than on the physical military force (Friedman, Ofer; Kabernik, Vitaly and Pearce, James C., 2019, p. 74).

Hybrid threats and hybrid wars of 21st century

As early as 1996, the US Marine Corps Commander, General Charles Krulak, in his speech at the Royal United Services Institute in London, said that the future of warfare was not the child of the Desert Storm, but the stepchild of Chechnya and Somalia (Krulak, 1996, p. 25). The concept of hybrid warfare describes a situation where external controlling force introduces potential protesting masses (otherwise unaware of being exploited) and different types of destructive opposition forces (e.g. terrorists, extremists and criminal groups) to the forefront of fight against opposing political regimes (Panarin, 2016). Thus, by waging a hybrid war, the external controlling power gains enormous operational opportunities to achieve its military and political goals without escalation into a full-fledged conventional conflict. Hybrid wars are characterised by the simultaneous incorporation of different modalities of warfare - conventional, irregular and terrorist, according to Frank Hoffman. He further adds that these multi-modal forms of warfare can be conducted by both state and non-state actors and the crucial difference is that they can occur at the same time and at the same place, and have non-linear multiple domains above and beyond the physical, including electronic, cyber or even more abstract cognitive or virtual elements. Another major characteristic of the hybrid quality is the combination of tactics and atypical means, such as crime, which is used to maintain the hybrid power, support disruption of the targeted nation, and prolong conflict. These combinations are not a mere coincidence; they are deliberately combined into a strategy designed to produce synergistic effects.

In other words, hybrid warfare, a combination of non-linear actions by the opponent, is not a product of a revolutionary impulse in the military realm, but simply a specialised model that offers more advanced methods and a better structure needed to achieve specific military and political goals, claims Filimonov. This is particularly the case where an external governing force (an international entity) needs to minimise the risk of conventional confrontation and employs various destructive forces, providing them with various types of situational support such as camouflaging the presence and participation of military contingents or by providing a superficial (information) cover up for covert subversive operations (Naumov, 2016, pgs. 73-86).

According to Hoffman, blurring the manner of warfare, blurring the identities of those fighting and the technologies brought in produces a wide range of diversity and complexity we refer to as hybrid warfare (Cf. Hoffman, 2007, p. 14). Hybrid threats incorporate a full range of modes of warfare, including conventional capabilities, irregular tactics and formations, and terrorist acts including indiscriminate violence and coercion, and criminal disorder (Ibid., 29). He defined hybrid threats as: “Any adversary that simultaneously employs a tailored mix of conventional weapons, irregular tactics, terrorism, and criminal behaviour in the same time and battle space to obtain their political objectives. (Hoffman, 2010, p. 443).

Hybrid threats are part of a transitional state of hostilities that is close to the direct application of armed violence but is commonly defined as a non-military threat, a possible form of an introduced insurgency by the opponent (Friedman, Ofer; Kabernik, Vitaly and Pearce, James C., 2019, p.61).

Hybrid war is a multidimensional phenomenon that integrates several aspects of combat - military, information, economic, political, and socio-cultural into one domain. What makes it characteristic is a combination of military and non-military influences that simultaneously extend across multiple battlefields and therefore require well-organized multi-vector resistance.

Multifaceted operations combine military measures (irregular insurgent tactics, use of special forces, information and cyberspace warfare, economic and political pressures) with civilian aspects of combat (public protests) (Nevskaya, 2015, pgs. 281-284). The civilian component, accompanied by a range of destructive techniques for dismantling political regimes, plays one of the most important roles in hybrid conflicts. Public protests, recently known as coloured revolutions, is a term that refers to specific techniques used to organize a coup and establish external control over the political situation in the target country. This is commonly achieved by artificially created political instability, where political blackmail is used to exert pressure on the government and where protests by opposition groups represent the strongest destabilising factor. As the demands of the protesters receive more media coverage, this allows for introduction of new political actors who put forward carefully designed political demands in order to bring the situation to a higher level of political confrontation. Therefore, a coloured revolution scenario is predominantly based on the employment of information warfare methods, where intelligence agencies, special forces and other military formations capable of changing the course of events, play a very important role, according to Filimonov. Therefore, the so-called coloured revolutions become the initial level of a much larger hybrid warfare.

Russian theory of hybrid warfare (Gibridnaya voyna) claims that it aims to destroy the political cohesion of the enemy from the inside by using carefully designed hybrids of non-military means and methods that reinforce political, ideological, economic, and other social divisions within the opponent's society, thus leading to its political collapse.

The International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) concludes that hybrid warfare involves: "the use of military and non-military tools in an integrated campaign designed to surprise, seize initiative, and gain psychological and physical advantage by utilizing diplomatic means; sophisticated and accelerated information, electronic and cyber operations; covert and occasionally open military and intelligence operations; and economic pressure” (Military Balance 115, no. 1, 2015, p. 5).

Mikhail Delyagin, Director of the Institute of Globalisation Problems, emphasizes the geopolitical importance of hybrid warfare, which he believes is a euphemism for global competition. He points out that "hybrid war is a fight that seeks to destroy an opponent, completely eliminate the independence of its governance system and put it under total control. A hybrid war seeks to reduce an adversary country (from its status as an independent state) to a territory under your rule” (Friedman, Ofer; Kabernik, Vitaly and Pearce, James C., 2019, p. 30). He further states that the means employed to that end are propaganda, bribe, political intrigue, espionage, political killings, and the staging of civil unrest.

The new information doctrine describes the information environment as a synergistic interaction of three dimensions: physical with infrastructure and links of information networks; informative, representing the actual material transmitted through physical networks; and cognitive, where the human brain gives meaning to a piece of information, and which has been described as the most important of the three (Armistead, 2010, p. 57).

In recent years, the British military has been navigating towards coordinated information operations where psychological and media operations are united behind holistic efforts to achieve clearly defined goals. This stems from the belief that changing attitudes through informative action is not enough. It increasingly emphasizes the goal at the expense of means and a sharpens the military focus on the result of behavioural change. This focus is still on the effects, but some influences now reach beyond the propaganda distribution of information influence distribution to combine with the intentional manipulation of the circumstances or conditions in which people act and make decisions (Briant, 2015, p. 64). It is no longer just about winning the hearts and minds, that is, "whether the Afghan like ISAF soldiers is irrelevant to the influential campaign, which simply seeks to change behaviour, not opinion" (Rowland and Tatham, 2010, p. 2). Matt Armstrong goes on to say that the phrase should now sound like a fight for the hearts and wills of people because the will to act is what matters. He points out that it does not matter whether someone likes you or not, the goal is to change that someone's behaviour. One of the leading thinkers in this field, Nigel Oakes, says that the behavioural revolution has happened inasmuch that the military now understands that changing human behaviour is the ultimate goal. A behavioural approach can potentially engage a wide range of information-related and other activities that only superficially appear to be unrelated to the desired final outcome to create behavioural changes among the targeted audiences. This includes assessing the circumstances under which behaviour will change and then using the influential activities to induce those circumstances, that is, to manage them. The desired change in the behaviour will not be apparent from the undertaken activities and the true intentions will be obscured by the process from an observer. It seeks to create a situation where the target of persuasion begins to make the "right decisions" without being aware that those decisions are the propagandist's wishes, Mackay says. The credibility of a propaganda message often requires the relative invisibility of a campaign within the global media environment.

Information warfare is an explicit and implicit interaction through information between different systems for the purpose of gaining certain benefits in the material sphere, argues Sergey Rastorguyev. He further adds that an information strike is carried out using the information weapons, i.e. such means that enable the intended actions to be carried out by transmission, processing, generation, destruction, and perception of information.

A significant aspect of Russian online information and psychological operations is the use of the so-called "trolls" (people-controlled) and "bots" (automatically-controlled). This broad system of fake accounts on social networks helps provide the necessary points of view in some debates by distracting and altering public attention or suppressing unwanted opinions. Their mimicry is complicated to detect because they accurately and faithfully simulate the behaviour and emotions of common people. As a method of information presentation, they are quite effective for the domestic and external environment and have become an integral part of the Russian information-psychological operations and information conflicts, as pointed out by Oxana Timofeyeva.

The main methods of information presentation for forming appropriate public opinion, as well as for modifying behavioural practices, were conceptualised during the information-psychological confrontation by Yury Kuleshov:

- Straightforward lie aiming to misinform the domestic and international audience;

- Cover up of critical information;

- Dissolution of important information in a plethora of data;

- Simplification, confirmation and repetition (suggestion);

- Terminology substitution: using concepts and terminology with unclear meaning or suffering qualitative changes, making it difficult to form a real picture of an event;

- Making certain types of information and journalism categories a taboo;

- Image recognition: well-known politicians or famous persons can participate in a political event and thus influence the worldview of their fans;

- Providing negative information, which garners more response from the public than the positive information (Fridman, Ofer; Kabernik, Vitaly and Pearce, James C., 2019, p. 158).

The so-called new wars theory claims that modern wars are qualitatively different from those of the past. Israeli military historian Martin van Creveld argues that modern wars are no longer primarily fought between states and their large professional armed forces, but involve a range of non-state actors including bandits, guerrillas and terrorists. He also argues that topics surrounding identity, such as ethnicity, religion, and gender, have become more central to conflicts than the traditional political and economic issues on which traditional analyses of war have been based. Kaldor agrees with Creveld, pointing out that new wars should not be confused with civil wars because new wars are confused and complicated and blur the lines between internal and external. Domestic violence can be perpetrated by external participants and can often be transnational links between state and non-state actors. As such, conventional concepts of conflict between states and within states are inadequate to explain contemporary conflicts, Kaldor believes. He states that the number of civilian casualties cannot be reliably determined at all in new conflicts.

Military theorist Evgeny Messner argues that in the future, the battle lines of conflict will be dissolved across the territories of conflicting countries, thus transforming political, social and economic aspects into the predominant dimensions of war. At the same time, a greater role will be given to the destructive influences on the civilian population:

"Every conflicting party will create and nurture partisan movements within its opponent's territory, promoting various opposition and defeatist parties and offering them ideological, material, financial, and propaganda support. All available means and methods would be employed to encourage civil disobedience, sabotage, subversion, and terror...” (Cf. Messner, 2004, p. 57). Sergey Konopatov and Vladimir Yudin believe that the new wars have a "velvety" hidden nature as they are more violent, intense and faster than previous ones. A significant feature of new wars is their longevity, and the reason for this persistence lies in the fact that participants in new wars often profit more politically and economically from committing violence rather than from simply winning. Kaldor emphasizes another important feature, namely, that old wars were associated with state-building, while new wars are a common opposite, they tend to contribute to the dismantling of a state and are often responsible for the downfall of states (Cf. Kaldor, 2013, p. 3).

Information operations and media as means

Fifty years ago, political efforts were about the ability to control and transmit scarce information. Today, political efforts are about creating and destroying credibility (Report of the Defence Science Board Task Force on Strategic Communication, September 2004, p. 20). The position of information in relation to national security was described by Neilson and Kuehl through the definition of information base: "Use of information content and technology as strategic instruments to shape fundamental political, economic, military, and cultural forces on a long-term basis to influence the global behaviour of governments, supra-governmental organisations and societies for the purpose of supporting national security” (Neilson and Kuehl, 1990, p. 40, in Kolobara, 2017, p. 81). Information has always been an element of power and often viewed as an enabler or component of support, not as a decisive factor in the conduct of operations; however, in this new era, it has the possibility considered to be crucial for the success of national security policies (Kolobara, 2017, p. 53). "Information power is difficult to categorise because it cuts across all military, economic, social, and political resources of power, in some cases diminishing their power, in others multiplying it" (Nye and Owens, 1996, p. 22). Understanding the power of information is more important than ever, because the contemporary world is now witnessing an onslaught of manipulative images, where nations, groups, and individuals are trying to manage the messages they receive.

Much of the information provided today, research, facts, statistics, explanations, and analyses eliminate the personal judgment and the capacity of an individual to form own opinion more certainly than the most twisted propaganda. This may come as a shock, but the fact is that excessive data does not enlighten the reader or the listener, but rather drown them, Ellul argues.

Former US Director of the Information Operations Institute, Jole Harding, described the range of possible information operations activities: "honestly ... the goal of what you are trying to do is limited by your imagination and special forces tend to think a little differently... Information can be used to terrorise someone, or to create conditions where one does not want to do something, or all kinds of things” (Briant, 2015, p. 12). He further explains that such actions, especially on the battlefield, can create chaos, distrust, suspicion, and even giving up the fight for one's cause.

Modern information and communication technologies enable the production, transmission and storage of information in a way practically impossible to control by the states. National borders are completely porous for all types of information flows, and barriers, artificial or natural, that once protected domestic public from unwanted foreign messages simply no longer work. World wide web and other erupting communication networks forever destroyed the power that once only governments had, and today's asymmetry gives the power of information to everyone.

Al-Qaeda and other terrorist organizations have made good use of the new media, harnessing the hunger of satellite television companies for news and using it to spread propaganda, show hostages and otherwise gain publicity. On the other hand, they count on the media to help them spread terror. Thousands were killed in the 9/11 attacks, but millions were terrified by the images provided by the media. Ayman al-Zawahiri once said, "that we are in a battle, and that more than half of this battle is taking place in the battlefield of the media; a media battle in a race for the hearts and minds of our Umma" (Arquilla and Borer, 2007, p. 86). Many argue that Al-Qaeda's success as a true player on the regional and global scene is more the result of an effective information strategy than of the military capabilities or inseparable political support it possesses. "Had Bin Laden had no access to global media, satellite communications and the Internet, he would have been just a grumpy guy in a cave," anti-terrorism expert David Kilcullen claims.

However, according to experts, Al-Qaeda has become much more than an organisation. Due to an effective information strategy, it has become a powerful idea. "It is obvious that media warfare is one of the most effective methods in this century; it can actually achieve 90% of the results in the preparation for a battle," Osama bin Laden said (Gordan Akrap, Special War 1).

Influencing the minds of the target audience requires identifying their psychological points or vulnerabilities. What can psychology do for warfare? A psychologist can pay attention to a particular person, to those elements of the human mind that are otherwise kept aside. They can show how to turn lust into anger, individual resourcefulness into mass cowardice, trust into distrust, prejudice into anger. They do so by going to the unconscious state of mind for the source of material. Secondly, a psychologist can set up techniques to discover how the enemy truly feels. Some of the worst misconceptions in history were the result of misjudgement on the state of the adversary’s mind. Beaufre argues that, with the addition of material factors, the art of battle consists of retaining and strengthening the psychological cohesion of one's troops while at the same time interfering with the enemy’s, hence the psychological factor is the key to success (Beaufre, 1965, p. 57).

If, for example, one group is presented with fake documents or facts, fake statements of its leaders on the things that matter to them, this can create a sense of weakness that can very quickly lead to despair and be a tipping point that will result in the breaking of their will. Also, the perception of injustice is one of the strongest motives for encouraging attacks, including aggression and war. "The perception of injustice arises when there is a discrepancy between the real destiny and the one that an individual thinks (s)he deserves" (Lerner, 1981, p. 11). As the basic human motivation, people try to restore justice, including resorting to violence and aggression, especially when injustice is perceived as a threat to one's own worth (Baumeister and Boden, 1998, p. 111). History of warfare is the history of perceived injustice, be the injustice real, made or imaginary, Pratkanis points out. Forced influence creates anger and resistance. We have a general tendency to react against coercive influence, be that coercion based on the use of force or deception or is the result of other manipulative processes. This tendency, defined as psychological inductive resistance, arises when an individual perceives that his/her freedom or behaviour is restricted; it is a repulsive condition that motivates behaviour in order to restore the threatened freedom (Brehm, 1966).

No one has done a better job of harnessing the anguish of Americans than the phrase war on terror, which the Bush administration frequently used between 2001 and 2009, Glassner claims. In this regard, former US National Security Advisor, Zbigniew Brzezinski, wrote for the Washington Post (25th March 2007), “The little secret here is that the vagueness of the phrase was intentionally calculated by its sponsors. The constant reference to the war on terror achieved one important goal: it stimulated the emergence of a culture of fear. Fear blurs reason, intensifies emotions and makes it easier for demagogic politicians to mobilise the public in the name of the politics they wish to pursue." Whenever a group uses fear to manipulate another group, someone profits and someone pays, Brzezinski observes.

One of the paradoxes of the culture of fear is that serious problems remain largely unnoticed, even though they actually pose a real threat to what the public fears most. The White House received the support it needed to attack Iraq by fuelling public fear of terrorism and associating it with Iraq. In the days before the attack, public support for the George W. Bush administration was 75%. Saddam Hussein was so successfully linked to the September 11 terrorist attacks in the public mind that in a New York Times poll in September 2006, long after the administration officially acknowledged that Hussein had nothing to do with the attacks, one third of Americans still thought that the Iraqi President was personally involved in them. FBI Director Robert Muller, when testifying before the Congressional Committee in February 2005, failed to emphasise the absence of terrorist attacks, failure to locate Al-Qaeda cells in the USA, or a report by his agency suggesting that Al-Qaeda may not have enough strength for a series of serious attacks in the USA. Instead, he was concerned. "I remain very concerned about what we don't see," he said. In his book Overblown, political scientist John Muller commented this by saying, "for the Bureau Director, the absence of evidence is clearly proof of existence." Other government agencies also had their own interests in inflating the threat of terrorism. Some did so to protect budgets. The DEA (Drug Enforcement Administration) made presentations how drug trafficking profit funds terrorism while the Office of National Drug Control Policy spent millions on a campaign that labelled teenagers using marijuana as terrorist financiers (Cf. Gardner, 2009, pgs. 266-270 in Kolobara, 2017, pgs. 62-63).

When it comes to the power of global media in creating public opinion, it is important to emphasise that the attention given to a particular party, or topic, statements taken from participants in an event or movement, greatly influence and create public opinion, mainly because one side of the “truth” is being pushed for, and only "what suits us" is singled out from the other side, thus providing (viewed from the aspect of journalism) objective reporting but aimed at provoking a specific emotion in viewers, which ultimately causes that viewer(s) to take a side and be susceptible to the propaganda messages coming from that side. This type of reporting, when an audience for the first time comes across a topic or a particular phenomenon, comes as the initial information that becomes established as the truth and becomes a base camp from which certain activity starts, either intellectual or operational. When a viewer with an already established negative or positive attitude about something encounters the influence of the media reporting differently from his/her attitude, (s)he (generally) automatically dismisses such reporting as incorrect and false and creates an even stronger conviction about the correctness of his/her opinion (Kolobara, 2017, p. 198).

Information operations’ impact

Public opinion is the king, Sorenson argues, pointing out that from the White House to other major centres of power, everyone is waiting and establishing their actions on public opinion. It can lift people and ideas to great power but also break them overnight. Sometimes it can cause wars and sometimes it can stop them. For example, on the night that Congress voted on the Iraq war, President Bush told the nation and the Congress that Iraq is an evil nation that threatens American security. Over the next few years, all key members of his administration made similar warnings in their speeches. According to the Congressional Special Investigation Report for Rep. Henry A. Waxman on public statements made by Bush administration officials, namely Bush, Dick Cheney, Rumsfeld, Colin Powel, and Condoleezza Rice, these five officials made 237 specific false and misleading statements about the Iraqi threat in 125 public appearances (Iraq on the Record: The Bush Administration's Public Statements on Iraq). Bush claimed that the very survival of the United States was at stake. Tony Blair went further, saying that the entire West faces a danger that is "real and existential" (Gardner, 2009, p. 13).

Attempts to isolate methods that are effective in changing strong beliefs show us that the key is in the volume and timing of the placement of contradictory information rather than in the quality. Large amounts of information presented in a short period of time have the greatest impact, Myers argues. The September 11 attacks on the United States are a prime example of the beliefs and attitudes that influence a final conclusion. Many enemies of the United States have come up with numerous theories that the US government had its fingers in the attack in some way. Of course, this is not true, but it turns out that the prejudice of those who dislike the United States have a key susceptibility to anything negative about the country. Rumours are most effective when triggered in a number of locations at the same time and in such a way that they go back and forth, with each new report apparently confirming the previous ones, claims Nigel West. Rumours circulated among Iraqis about how US soldiers used their night vision goggles to spy on Muslim women and distributed pornographic content to children, played a major role in starting the fierce fighting in Iraqi Fallujah. A local Iraqi bakery acknowledged that "these rumours affected people in a negative way... They encouraged people to use their weapons against Americans" (Los Angeles Times, 14th June 2003).

Commenting on Western media coverage of Syria (2016), Canadian journalist Eva Bartlett said that "everything you hear and read in corporate media is the exact opposite of the reality." She points out that corporate Western media is engaged in planning regime change in Syria. She also said that she had been throughout Syria several times and that the people were giving a great deal of support to the President of the country, "and that this is contrary to what you read in corporate media like the BBC, the New York Times or The Guardian." She further states that those media reports are completely opposite to the reality and that they aim to demonise Assad and Russian support for Syria. In particular, Bartlett points out that all of those media rely on the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights as its source, which is in fact a British organisation based in Coventry, England, with only one member. Bartlett cited the so-called White Helmets as an example of manipulation and explained that it was an organisation formed in 2013 by a former British officer and funded with $ 100 million from the US, UK and the EU. "They are supposed to be rescuing civilians in East Aleppo, but no one has heard of them there! The White Helmets are allegedly independent, but you can see them carrying weapons and standing next to the bodies of dead Syrian soldiers (Assad supporters). Their videos show the same children they use for different reports, so you may notice the girl Aja, who appears at different times in different locations” (www.bljesak.info, 15th December 2016).

For example, in 2015 and 2016, numerous articles written by journalists were published in various Russian media, commenting on the Ukraine-EU deal. In short, the story was that in exchange for a visa-free regime with the EU, Ukraine committed to accepting refugees from the Middle East to its territory. Cover pages of newspapers in Russia were more than colourful, "EU will force Ukraine to accept migrants from Africa and Middle East", "Ukraine was offered to have migrants settle in exchange for visa-free regime with EU", "Ukraine started building camp for Syrian refugees” (Friedman, Ofer; Kabernik, Vitaly and Pearce, James C., 2019, p. 161). Oxana Timofeyeva states that this is an example of a long-lasting information and psychological operation that revealed methods of direct lying and transfer of conclusions and derivatives, which is a specific case of transformation as well as the method of finding facts, that is, mixing fiction and reality. The main objective of this operation was to reconstruct the image of a negative future in the minds of the audience and discredit the government’s intentions using the European "problem" in Ukraine.

Igor Nikolaychuk, on the other hand, gives examples of the Russian-American relations. He alleges that the US media demonized the Russian authorities in the case of Dima Yakovlev in 2012 and 2013. For every twenty to twenty-five negative articles on Russia, there came only ten neutral ones, with absolutely no positive articles. When it comes to the Ukraine case, the US media again labelled Russia the axis of evil. In August 2015, for every thirty to thirty-five negative articles came ten neutral ones. In September, after operations in Syria, there were ten neutral articles for every twenty-five negative ones about Russia (Nikolaychuk, Yakova and Yanglyaeva, 2016, pgs. 12-24).

Research

During October 2019, a sociological field survey was conducted on a sample of 600 citizens in three large BiH cities, Banja Luka, Sarajevo and Mostar. The aim of the research was to examine the public's level of knowledge about the terms and topics of hybrid threats and warfare and related activities. A total of 603 persons participated in the research, of which 48% were male (N = 286), 52% were female (N = 316), while one participant (N = 1) did not state his/her view when prompted.

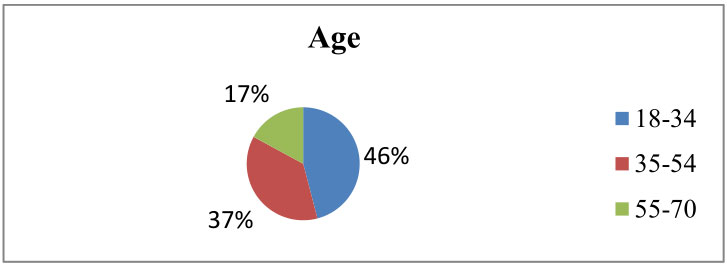

As for the age distribution, 46% (N=277) of the participant are aged 18-34, 37% (N=223) are aged 35-54, and 17% (N=103) are aged 55-70.

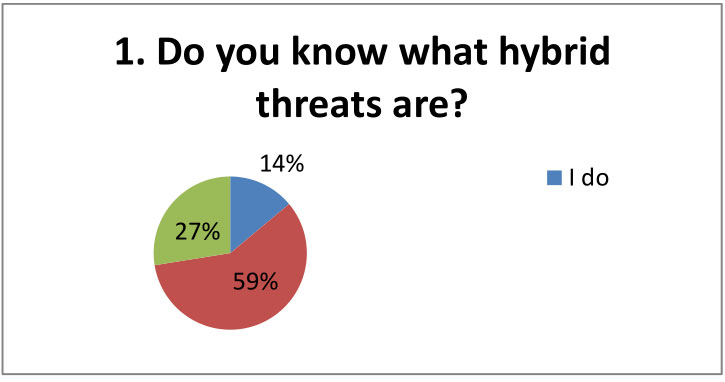

When asked, Do you know what Hybrid threats are, 59% (N = 353) of the participants said they did not know, 27% (N = 166) knew about them, but did not know enough about it, and 14% (N = 84) said they knew what they were.

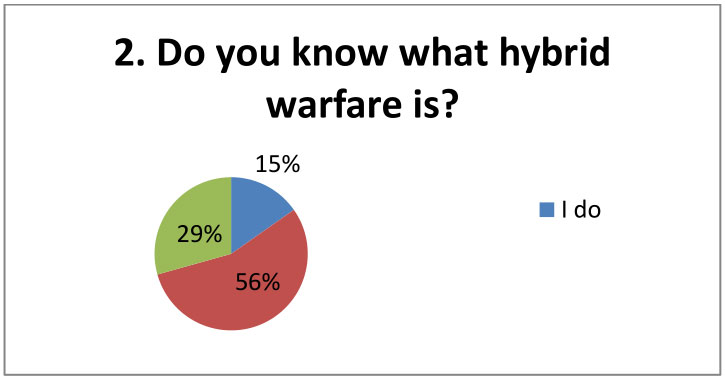

When asked Do you know what hybrid warfare is, 56% (N = 334) of the participants stated that they did not know, 29% (N = 177) that they knew, but did not know enough about it, and 15% (N = 92) said they knew what it was.

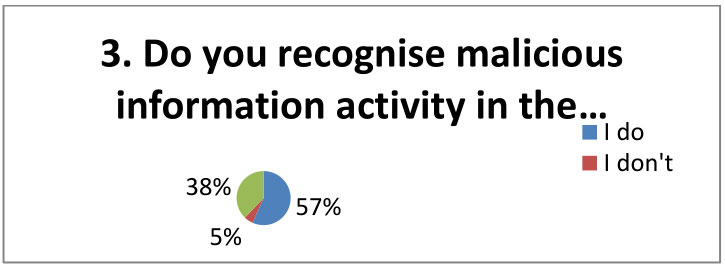

When asked, Do you recognize malicious information activity in the media, 57% (N = 342) of the participants stated that they recognised it, 5% (N = 33) did not recognise it, and 38% (N = 228) recognised it partially.

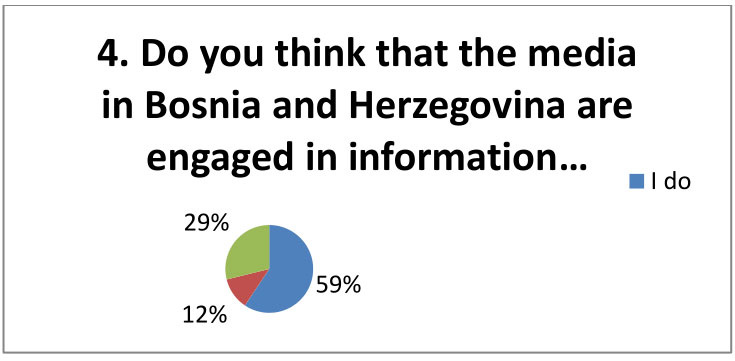

When asked, Do you think that the media in Bosnia and Herzegovina are engaged in information warfare, 59% (N = 358) of the participants stated that they thought it was, 12% (N = 71) did not think that, 29% (N = 174) did not know.

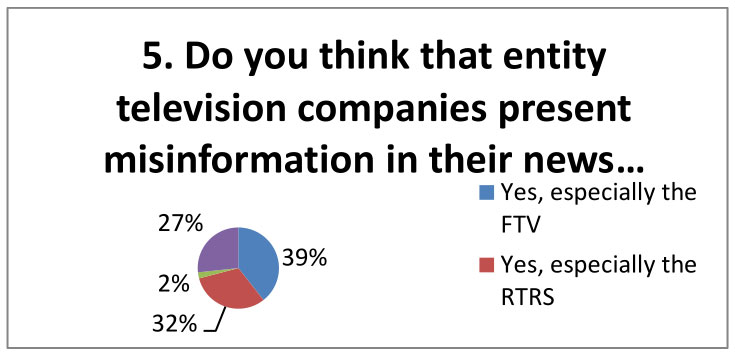

When asked, Do you think that entity television companies present misinformation in their news programmes, 39% (N = 310) of the participants said Yes, especially the FTV (the FBiH television, whose editorial policy is predominantly influenced by the Bosniak political elite); 32% (N = 248) Yes, especially RTRS (Republika Srpska Television, whose editorial policy is predominantly influenced by the ruling Serb political elite); 2% (N = 19) No, and 27% (N = 210) answered, I don't know.

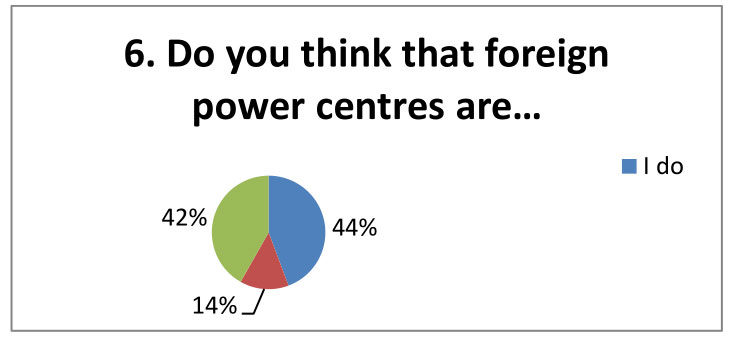

When asked, Do you think that foreign power centres are conducting hybrid warfare in BiH, 44% (N = 267) of the participants said they thought they were, 14% (N = 84) did not think that, while 42% (N = 252) did not know.

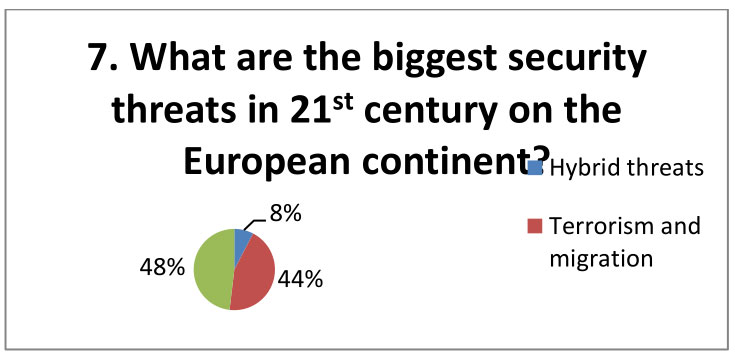

When asked, What are the biggest security threats in 21st century on the European continent, 8% (N = 55) said hybrid threats, 44% (N = 318) answered terrorism and migration, 48% (N = 346) said political extremism.

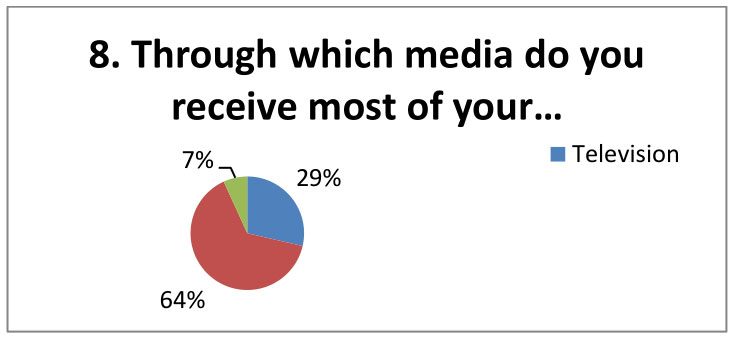

When asked, Through which media do you receive most of your information, 29% (N = 210) said via television, 64% (N = 474) via the world wide web and social networks, and 7% (N = 50) said via radio and newspaper.

Testing the relevance of difference in answers to the questions in view of gender

Statistically relevant difference were established in view of gender in the responses to the question Do you recognise malicious information activity in the media (c2 =4,23; df=1, p<0.05). More men, compared to women, said they recognised it, 63% of men to 51% of women; and in the responses to the question Do you think that foreign power centres are conducting hybrid warfare in BiH? (c2 =2,18; df=1, p<0.05). More men, compared to women, said they did, 50% of men to 39% of women.

Statistically relevant difference were established in view of gender in the responses to the question Through which media do you receive most of your information (c2 =3,85; df=1, p<0.05). More men in comparison to women said they received information via television, while more women received information via world wide web and social networks.

1. Through which media do you receive most of your information?

|

Gender

|

Men

|

Women

|

|

Responses

|

N (%)

|

N (%)

|

|

Television

|

138 (48)

|

72 (22.78)

|

|

World

wide web and social networks

|

143 (50)

|

242 (77)

|

|

Radio and

newspaper

|

4 (2)

|

2 (0.22)

|

In case of other questions, no statistically relevant differences were found in the responses in view of gender.

Testing the relevance of difference in answers to the questions in view of age

Statistically relevant difference were established in view of age in the responses to the question Do you know what hybrid threats are (c2=3,46; df=2, p<0.05). More older respondents (35-24 and 55-70) said they knew, when compared to the younger respondents (18-34).

2. Do you know what hybrid threats are?

|

Age

|

18-34

|

35-24

|

55-70

|

|

Responses

|

N (%)

|

N (%)

|

N (%)

|

|

I do

|

14 (5)

|

46 (21)

|

24 (23)

|

|

I don’t

|

192 (69)

|

101 (45)

|

60 (58)

|

|

I’ve

heard about it, but I don’t know enough about it

|

71 (26)

|

75 (34)

|

18 (19)

|

Also, in responses to the question Do you know what hybrid warfare is (c2 =2,86; df=2, p<0.05), more older respondents (55-70 and 35-24) said they knew, when compared to the younger respondents (18-34) 20% and 28% to 7%.

|

Age

|

18-34

|

35-24

|

55-70

|

|

Responses

|

N (%)

|

N (%)

|

N (%)

|

|

I do

|

19 (7)

|

44 (20)

|

29 (28)

|

|

I don’t

|

182 (66)

|

97 (44)

|

55 (54)

|

|

I’ve

heard about it, but I don’t know enough about it

|

75 (27)

|

81 (36)

|

18 (18)

|

Statistically relevant difference were established in view of age in the responses to the question Do you think that entity television companies present misinformation in their news programmes (c2 =2,11; df=2, p<0.05). More older respondents (55-70 and 35-24) responded that it was the entity TV station FTV.

When asked Do you think that foreign power centres are conducting hybrid warfare in BiH (c2 =4,72; df=2, p<0.05), more older respondents (55-70 and 35-24) responded yes, 57% and 66% to 28% (18-34).

Statistically relevant difference were established in view of age in the responses to the question Through which media do you receive most of your information (c2 =7,36; df=2, p<0.05). More older respondents said they received information via television, when compared to the younger respondents, while the youngest respondents (aged 18-34) receive most of their information via world wide web and social networks.

3. Through which media do you receive most of your information?

|

Age

|

18-34

|

35-24

|

55-70

|

|

Responses

|

N (%)

|

N (%)

|

N (%)

|

|

Television

|

57 (21)

|

94 (42)

|

59 (57)

|

|

World

wide web and social networks

|

220 (79)

|

124 (56)

|

42 (41)

|

|

Radio and

newspaper

|

0 (0)

|

4 (2)

|

2 (2)

|

Note: c2 – value of hi squared; df- degrees of freedom <0.05 considerably at 5 %

Conclusion

Information operations always present themselves to be what they are not. Their ideological base, while seemingly incoherent at first, is essentially an imitation of theological concepts of action targeting audience with only short-term activities that can be caused time and again. They are in fact a laboratory example of perfect copying, that is, imitation of what was relayed, into another context of action. In a religious context, any questioning of religious authority is considered impermissible, and one who does so is described in the worst terms. The same was manage to be achieved in information operations. The only credible source right now is the position of authority (media, that is, institutions and other positions of the ruling elite) that draws authority over “truth”, which must not be doubted, from the very position of authority and need not rationally justify it. It is enough that it is convincingly repeated countless times, that is, presented in different ways in order to create the illusion of intellectual diversity. Media information should only be viewed as an appearance on the surface, as a form filled with content of interest character packed into a seemingly objective phenomenon. Judging the most important things on the basis of the first impression and media rumours is often a bad and incorrect judgment precisely because based on what you saw you can only discern the surface (which is often deceptive), while based on what you hear, you can only discern misinformation that suggests a completely opposite conclusion. The sharpness of judging the effect of an information action is inversely proportional to the immediate proximity of the object in a development. The closer you are, the less reasonably you see, and more act in the heat of the moment, while things get clearer the more you move away and the less emotionally involved you are. The goal of the present-day media information operations is to overthrow reality, i.e. to establish imposed perceptions and understandings that lead to the same way of thinking that will ultimately trigger the desired action. The nature of the targeted information for a particular recipient will always be negative from at least one point of view, because its value determinant is formed depending on the position of interpretation. We primarily need to be interested in the structure of information in the whole context of events, in its awareness and then in its content.

Criticisms of modern security concepts navigates towards attacking the universal supervision introduced by states as a practice. Emphasis is placed on the fact that our constantly monitored behaviour is reduced to slow simmering in the world of convenience, to conformist behaviour, self-censorship, and mere consumerism presented as freedom of choice. Emphasis is also on the fact that our whole personality is presented to the public, and that all those who think they should not be afraid because they are doing nothing wrong will realise over time that they have been manipulated. In the end, it all comes down to the individual's autonomy being erased under the guise of the individual as a new reference object of security. The contemporary intelligence apparatus no longer needs (to such an extent) agents who will "hunt" citizens (targets) around the country. Nowadays, this is done by the computers monitoring their activities through smartphones, social networks, CCTV, credit cards, etc. Security thinking and positioning must be updated in line with technological changes. In the past, human political aspirations were aiming for freedom, while "in the political present day" they are permanently imprisoned in the domain of safety and comfort. If the theory that history is the teacher of life is correct, then countries do not have to wonder whether there will be a war, but when it will begin. Therefore, the military category of security for the state (in the broadest sense), in the long run, still remains, or must remain, in the first place.

Hybrid threats and wars are the new security modus operandi of the 21st century and will certainly remain a current topic for several decades to come. They have demonstrated their effectiveness and pervasiveness in numerous international conflicts and operations, irreversibly affecting their final outcome. It is the diversity, the polyvalence of the tools they use, and the totality and the omnipresence of the operational knowledge, skills and reach they produce that make them the scary category of operational threats that represents all the best that military, intelligence, propaganda, and cyber capabilities and experiences can deliver today.

Research conducted in BiH on knowledge of the concept and terms of hybrid threats and warfare and related activities found that the general population is largely unaware of what hybrid threats and hybrid wars are. Thus, many of those who answered affirmatively about their knowledge (mostly the older population) most often confused hybrid threats with agricultural terminology and actions in the comments they made orally after completing the survey. 44% of respondents believe that foreign power centres are conducting hybrid warfare in BiH and express negative opinions and emotions about the interference of the foreign political factor in BiH. Only 8% of respondents identify hybrid threats as the biggest security threat in the 21st century on the European continent, while the majority 48% label political extremism as the greatest threat to European security in 21st century. The survey also found that 64% of those surveyed use the world wide web and social networks as their main source of information, compared to 29% of those who use television. Majority of respondents rated themselves as recognising malicious information activity in the media, found that the media in BiH (referring to state entity broadcasters) were conducting information warfare and labelled the FBiH Television (39% of respondents) as the one broadcasting misinformation in its news programme. Accordingly, a conclusion can be reached that entity television reporting should be viewed using a holistic approach, that is, one that says that details and particular phenomena must always be viewed in a context. There is no doubt whatsoever that this context is driven by some particular interest(s) and for someone’s benefit.

In the end, the human psyche works the same way it did 2 or 3 thousand years ago. People have not changed, only technology has. Today, we need a security-information capability to see, to discern, and consequently, not respond. You cannot change the way foreign security and political media gravity works, but you can adapt and utilise it. If something sounds as a fact it does not necessarily mean it is a fact. After all, facts no longer matter, only narrative does.

Bibliography

- Arquilla, John - Borer A. Douglas (2007.) Information Strategy and Warfare - A guide to theory and practice. Routledge, New York and London.

- Armistead, Leigh (2007.) INFORMATION WARFARE - Separating Hype from Reality; Potomac Books, Inc. Washington, D.C.

- Akrap, Gordan, Specijalni rat - Sve o spregama politike i tajnih službi u 20. stoljeću u cilju oblikovanja javnog mišljenja, Večernji list, Oreškovića 6H/1, Zagreb.

- Alexander Naumov, „Soft Power and Color Revolutions“, Rossiyskiy zhurnal pravovykh issledovaniy 6, no. 1 (2016): 73-86.

- Andre, Beaufre (1965.) An Introduction to Strategy, New York, Praeger.

- A. Silke, „Analysis: Ultimate Outrage“ The Times (London), May 5, 2003.

- Briant, Emma Louise (2015.) Propaganda and Counter-Terrorism – Strategies for Global Change. Manchester University Press, Manchester, UK.

- Baumeister, R. F. - Boden, J. M. (1998.) “Aggresion and the self: High self-esteem, low selfcontrol, and ego threat”, u: R.G. Geen - E. Donnerstein (ur.), Human Aggresion, San Diego, Academic Press, str. 37-111.

- Baudrillard, Jean. (2001.) Simulacija i zbilja. Zagreb: Naklada Jesenski i Turk.

- Christoper, Paul (2008.) Information operations - Doctrine and Pratice (A Reference Handbook), Contemporary Military, Strategic, and Security Issues; Praeger Security International; Wetport, Connecticut, London.

- Charles, Krulak, „The United States Marine Corps in 21 st Century“, RUSI Journal 141, no.4 (1996): 25

- Collins, Alan (2010.) Suvremene sigurnosne studije. Politička kultura, Zagreb.

- Gardner, Daniel (2009.) The SCIENCE of FEAR, Penguin Group, London, England.

- „Editor's Introduction: Complex Crises Call for Adaptable and Durable Cababilities“, The Military Balance 115, no. 1 (2015): 5.

- Evgeny Messner, „Worldwide Subversion-War, (Moscow: Zhukovskoye Pole, 2004), p. 57.

- Fridman, Ofer; Kabernik, Vitaly and Pearce, James C. (2019.) Hybrid Conflicts and Information Warfare – New Labels, Old Politics. Lynne Reinner Publishers, Boulder London, UK.

- Freedman, L. ‘Conclusion: The Future of Strategic Studies’, in J. Baylis J. Wirtz E. Cohen C. Gray (eds), Strategy in the Contemporary World: An Introduction to Strategic Studies, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002, 328– 342.

- Gardner, Daniel (2009.) The SCIENCE of FEAR, Penguin Group, London, England.

- Hoffer, Eric (1989.) The True Beliver: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements, New York: Harper Perennial.

- Hough Peter, Shahin Malik, Andrew Morgan and Bruce Pilbeam (2015.) International Security Studies – Theory and Practice. Routledge, New York.

- Hafez, Kai (2007.) The Myth of Media Globalization. Cambridge: Polity.

- Hoffman, Frank, „Hybrid Threats: Neither Omnipotent nor Unbeatable“, Orbis 54, no. 3 (2010): p. 443

- Hoffman, Frank (2007.) Conflict in the Twenty-First Century: Rise of Hybrid Warfare (Arlington, VA: Potomac Institute for Policy Studies).

- Igor Nikolaychuk, Tamara Yakova and Marina Yanglyaeva, „Media as a System-Trend: New Approaches im Medialogy“, Mediaal 'manakh, no. 1 (2016): 12-24.

- Igor Panarin, Hybrid War Against Russia, 1816-2016, Moscow: Goryachaya Liniya-Telekom, 2016).

- „Iraq on the Record: The Bush Administration's Public Statements on Iraq“, prepared by the House of Representatives Committee on Goverment Reform – Minority Staff's Special Investigations Division, March 16, 2004, available at www.reform.house.gov/min/

- Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Doctrine for Information Operations, Joint Publication 3-13 (Washington, DC, February 13, 2006), I-1.

- Jon B. Alterman, "The Information Revolution and the Middle East" in The Future Security Enviroment int he Middle East: Conflict, Stability, and Political Change, eds. Nora Bensahel and Daniel L. Byman (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2003).

- Kolobara, Robert (2017.) IDEOLOGIJA MOĆI – informacija kao sredstvo, Udruženje za društveni razvoj i prevenciju kriminaliteta - UDRPK, Mostar.

- Kaldor, M. ‘In Defence of New Wars’, Stability: International Journal of Security and Development, vol. 2, no. 4, 2013, 1– 16.

- Lerner, M.J. (1981.) „The justice motive in human relations: Some thoughts on what we know and need to know about justice“, u: M.J. Lerner – S.C. Lerner (eds), The Justice Motive in Social Behavior (pp. 11-35), New York, Plenum.

- Nye, J.S., and W.A. Owens. "America's Information Edge." Foreign Affairs 75 (March/April 1996): 20-36.

- Pingeot, L. Dangerous Partnership: Private Military and Security Companies and the UN, Global Policy Forum, www.globalpolicy.org/ images/ pdfs/ GPF_Dangerous_Partnership_Full_report.pdf, 2012 (Accessed 28.6.2014).

- Panarin, Igor (2012.) Mass Media, Propaganda and Information Warfare, Moscow: Pokolenie.

- Rowland, Lee and Tatham, S. (2010.) Strategic Communication & Influence Operations: Do We Really Get It?, Shrivenham: Defence Academy of the United Kingdom.

- Soroos, M. (1997.) The Endangered Atmosphere: Preserving a Global Commons, Columbia: University of South Carolina Press.

- Stremlau, J. (1994.) „Clinton's Dollar Diplomacy“, Foreign Policy, No. 97, 18-35.

- Schwartz, M. and Church, J. ‘Department of Defense’s Use of Contractors to Support Military Operations: Background, Analysis, and Issues for Congress’, Congressional Research Service, www.fas.org/ sgp/ crs/ natsec/ R43074. pdf, 2013 (Accessed 28.6.2014).

- Seib, Philip. (2008.) The Al Jazeera Effect – How the new Global media are reshaping world politics. Potomac Books, Inc. Washington, D.C.

- Thomas L. Friedman (2003.) Longitudes and Attitudes: The World int he Age of Terrorism, New York: Anchor Books.

- Tatyana Nevskaya, „The Information Component of Hybrid Wars“, Vestnik Moskovskogo universiteta, Seriya 18, Sotsiologiya i politologiya 4 (2015): 281-284.

- U.S. Department of Defense, Office oft he Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics, "Report oft he Defense Science Bord Task Force on Strategic Communication" (September 2004), 35.

- Vladimir Lisichkin and Leonid Shelepin, (2003.) The Third World (Information-Psychological) War, Moscow: Eksmo, Algoritam.

- Waller, J. Michael ed. (2008.) Strategic Influence – Public Diplomacy, Counterpropaganda and Political Warfare. The Institute of World Politics Press, Washington.

- www.bljesak.info/rubrika/vijesti/članak/kanadska-novinarka-otkrila-zapadni-mediji-lažu-o-aleppu-i-siriji/179925 Thursday 15. December 2016. 13:06