DOI: https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.24.3.2

Original scientific paper

Received: October 23, 2023

Accepted: December 8, 2023

Abstract: The advent of the digital revolution has introduced several means for the collection, spread, and dissemination of information within the realm of communication, thus transcending geographical and time constraints. The swift digitization and transformation of contemporary societies have created an unusual security landscape, exerting its influence across every facet of human, societal, economic, and political life. Technology stands as a pivotal variable in the dynamic evolution of terrorism.

Cyberspace has emerged as a fertile domain for the amplification and continuation of terrorist activities, representing a profound “transformation” at the operational level over recent decades. Terrorists have adeptly seized upon the potential of cyberspace, strategically imitating successful tactics employed by like-minded, assimilating lessons from past mistakes, and adapting to exigencies of both the present and future. The extensive deployment of information communication and technologies (ICTs) has substantially facilitated terrorists’ activities in a multitude of ways. This includes cost reduction, the generation of operational efficiencies, broader access to novel target demographics, the provision of anonymity, heightened security measures, the dissolution of organizational barriers, and the amplification of the scope and reach of their actions. The full spectrum of cyber activities conducted by terrorists can be comprehensively encapsulated within a model titled the “Digital Jihad”. This paper intends to apply this model in the context of examining the activities and strategies of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS).

Keywords: Digital Jihad, ISIS, virtual radicalization, strategic communication, hacking, social media, cyberterrorism.

Introduction

With over 5,3 billion users in cyberspace, constituting 66% of the global population, its indispensability in our daily lives is essential. In an era dominated by selfies, snaps, likes, hashtags, and shares, the ICTs have transformed the way of communication and spread of ideas. The swift digitalization of society is creating a new security landscape, posing significant challenges across all aspects of our lives. The impact of digital technology extends to the realm of security, with terrorism undergoing a profound transformation in the last decades. Terrorism has emerged as one of the major security threats due to the size, frequency, and scope of its actions, and adaptive capabilities. The rise of Jihadist groups, integral parts of global networks like Al Qaeda and ISIS, further underscores the complex challenges posed by the digital era.

Over the past decades, terrorism has advanced with the extensive use of ICTs, since every extremist movement across the ideological spectrum has exploited digital technology, thereby digitalizing their actions. Hence, there is a dominant relationship between terrorism and cyberspace (Hoffman, 2017, p.56). The digital era facilitates those who want to amplify violent physical actions swiftly and easily into the information environment, solely via digital technology. It is safe to argue that many terrorist organizations owe their survival and expansion to digital technology. This leads to the assertion that terrorism leaves a distinct ‘digital footprint’, considering the interconnectivity of society (Kapsokoli, 2023). Thus, cyberspace is a potential field where terrorism can flourish. Terrorists demonstrate remarkable resilience in the digital sphere, positioning themselves as effective adopters of digital technology. Their adaptability allows them to adjust their modus operandi as per the political and social imperatives, ensuring their continued existence. It should come as no surprise that terrorists can learn, innovate, and adapt to the new technological imperatives of each era (Kapsokoli, 2019, p.677). Nowadays, these actors have both the motivation (religious faith) for operational action, but also the means for its effectiveness (ICTs) (Kapsokoli, 2023).

There are two approaches to cyberterrorism, a narrow and a broader one. The narrow approach confines cyberterrorism to malicious cyber activities, such as employing ICTs to target critical infrastructure. On the contrary, the broader approach encompasses a wide range of malicious cyber activities, aiming for a more holistic understanding that recognizes the true potential of cyberspace for terrorists (Kapsokoli, 2021, p.40).

This paper aims to examine the utilization of cyberspace by ISIS for its activities. The initial focus involves a comprehensive analysis of ISIS’s digital activities through the ‘Digital Jihad’ model. Subsequently, it reviews empirical evidence about ISIS’s involvement in radicalization, recruitment, operational training, strategic communication, funding, online matching, and hacking. The main research question implicit in the following article is how ISIS utilizes cyberspace for its operational activities through the ‘Digital Jihad’ model.

Analyzing the “Digital Jihad” model

Cyberterrorism reflects the ‘dark realm’ of cyberspace since the latter is used for two reasons. The first is to develop malicious cyber activities, such as cyberattacks. The possibility of a terrorist organization conducting a cyberattack on a military or financial system is considered a major security threat (Yannakogeorgos, 2014, pp.43-62). The second reason is to facilitate a full spectrum of terrorist actions, which provides a fertile ground for the rise of radical ideas that lead to terrorism (Helland, 2000, pp.205-223). In general, terrorists through their actions strive to increase the influence and impact of their messages to attain short-term and long-term goals. Terrorists struggle to gain publicity and recognition to make their existence, tactics, political goals, and ideological background known to the public. Publicity can be generated by the freedom of information in the mass media or the freedom of speech and a broader global audience on social media.

Cyberspace acts as an amplifier of terrorism since it removes traditional physical barriers. Terrorists intend to induce fear and terror in the global society but also serve as an example for other like-minded actors to imitate and mobilize (Briggs, 2011, pp.1-20). The latter is drawn by the terrorists’ actions and the content of their propaganda, they sympathize and express a will to support the terrorists, developing a kind of moral obligation to contribute to the struggle by conducting terrorist actions (Chapsos, 2010, pp. 28-35). Terrorist actions have an impact mostly on younger individuals who are more susceptible to influences that shape their will and personality. Potential terrorists have the appropriate expertise and can successfully become members of a terrorist organization or act independently. Cyberspace reinforces an ideological background with extremist ideas because it is a fertile ground for finding and developing these kinds of ideas (Silber and Bhatt, 2007). Terrorists can express their religion with the use of these means and the construction of digital religious communities.

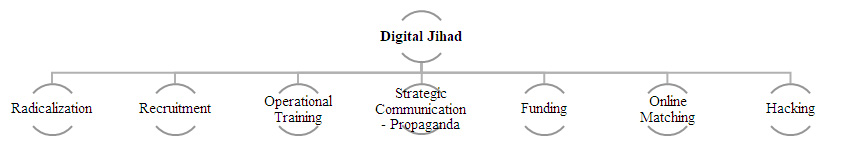

Jihadist groups (e.g., Al Qaeda, ISIS, Hamas, Hezbollah, Boko Haram, Al-Shabaab, etc.) have significantly expanded their presence in the digital sphere and on social media platforms. This evolution has added greater complexity and depth to the landscape of terrorism. These groups have harnessed increasingly decentralized electronic networks to acquire and disseminate technical knowledge. They function beyond the geographical confines of traditional control zones, leveraging emerging technologies, and developing unusual technological strategies when faced with disruptions to their communications and organizational structure. This vicious cycle of operational innovation and adaptation poses a challenge for counterterrorism. In general, terrorists are using cyberspace for operational activities such as radicalization, recruitment, operational training, strategic communication – propaganda, funding, online matching, and hacking. The below figure “Digital Jihad” refers to the main uses of cyberspace by terrorists, which vary on the type of terrorist organization and their political goals (Kapsokoli, 2023).

Figure 1. “Digital Jihad”

ISIS’s digital character of terror

Al Qaeda in Iraq (later named ISIS) was born after the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, but the turning point was the civil war in Syria and the Arab Spring in 2011 (Cockburn, 2014, p.31). ISIS has been characterized as an anachronistic terrorist organization, and its name became synonymous with brutal violence and imperialist ideas. It managed to adapt to today’s technological, political, and social imperatives and the demands of this era by using contemporary means (cyberspace and ICTs) to promote outdated political goals. Its political goals were intended to restore traditional Islam to contemporary society, to achieve territorial sovereignty in Iraq and Syria (Cronin, 2015, pp.87-98), to spread at the same time their jihadist ideology, to gain publicity, and to have an impact on its actions (McNair, 2008, pp.245-246, 261-262).

Compared to other like-minded terrorist organizations, the technological superiority and sophistication of ISIS is noticeable. It adopted new, efficient, and long-term strategies in the digital world, to be able to expand and preserve its presence in the global chessboard of terrorism. ISIS had taken advantage of the possibilities offered by Web 2.0 in every feasible way to achieve its goals (Kadivar, 2020, pp.1-28). It developed a tremendously sophisticated information campaign with a wide range of global audiences to gain support and instill fear in the public. The oxymoron with ISIS is that it prohibits modern behaviors and means, but it managed to digitalize its operational action uniquely. This turning point happened at a time when people were dependent on ICTs and social media.

Radicalisation

ISIS copied the communication and marketing techniques and strategies of Western companies and tailored its narratives to a diverse audience, especially the youth, who constitute most Internet users. A shared sense of belonging and unity emerged, with the creation of a ‘virtual Muslim community’, where jihadist ideas and practices were freely developed (Meleagrou-Hitchens and Kaderbhai, 2017). The only prerequisites were a smartphone and an internet connection, allowing users to express their ideas freely and openly, without the fear of being deplatformed.

The virtual character of radicalization promotes self-radicalization, in a brief period, facilitated by the extensive and effective use of cyberspace. This resulted in the creation of a completely functional virtual ecosystem, which includes online libraries, Jihadi websites, online fora, chat rooms, filter bubbles, and echo chambers (Wiktorowicz, 2015, pp.75-97). Within this ecosystem, users have access to sources of information [video, magazines, books, manuals, recordings, religious sermons (Khutbas), and Arabic songs (Nasheeds)] intensifying the radicalization process (Gendron, 2017, pp.44-61). This digital material was published in high quality and numerous languages, which was available to a broad and multinational audience. The radical content was directed at both Muslims and non-Muslims, independently of their nationality and language, while the increased number of foreign fighters mitigated the feeling of ‘foreign’ among the new members (Siboni et al., 2015, pp.127-140).

Those responsible for radicalization emphasized the message recipients and their behavior. They formed a digital relationship, which was full of “promises of friendship, acceptance and a sense of purpose”. This facilitated the psychological manipulation and the construction of radical behavior by casting doubts on individuals’ current lifestyles and persuading them to embrace a fresh start offered by ISIS (Winter, 2017, pp.6-46). Radicalized members fulfilled their desire to belong, to regain their lost self-esteem, to give meaning to their lives, to revenge, to increase prestige, and to live an adventure (McCauley and Moskalenko, 2008, pp.415-433). They used the method of “target-groups” to tailor the approach to the social, economic, religious, and ideological demographics of specific groups. Utilizing tactics such as “social mapping” and “profiling” enabled them to collect all the necessary information for a tailored approach (Provost et al., 2011). Users often overlook the daily role of social media, and publish all their personal information unfiltered, thus providing all the needed information to malicious actors. ISIS has created the concept of “Jihadi cool”, which refers to the promotion of an ideal image of the life of the radicalized that is equivalent to a star (Nesser, 2019, 15-21). They created reputations regarding their actions and their political goals based on their general perceptions. This tactic was intended to radicalize young fighters, offering them an alternative way of life based on jihad.

The online magazines of ISIS were the basic means used for the radicalization of fighters, in which references were made to the ideological background, goals, and actions of the organization. All magazines were dated according to the Arabic Calendar (Hijri), had religious content with radical elements, and used Arabic symbolic names, and historical events. Their content was sufficient in promoting the construction of a new identity for potential fighters, by the principles advocated by ISIS (Kapsokoli, 2023). The publications were in different languages (English, French, German, Russian, Hindi, and Arabic) to approach different audiences. Some important examples from ISIS’s digital magazines were ‘Dabiq’, ‘al-Naba’ (The News or The Report), ‘Dar al-Islam’ (House of Islam), ‘Konstantiniyye’, ‘Istok’ (The source), ‘Rumiyah’ (Rome), and ‘Voice of Hind’ (Looney et. al, 2017, pp. 182-193).

In the Western Balkans, a trend emerged by using online platforms for free religious lectures delivered by charismatic and influential Jihadist preachers (Da’is) to attract followers. Digital religious classrooms were established to boost jihadist beliefs. Typical examples were the cases of Safer Kuduzovic and Elvedin Pezic (Bećirević, 2018, pp.9-13). Noteworthy is the role of Anjem Choudary, who served as an ulama in three Islamic organizations, namely, the Al-Muhajiroun (Immigrants), the Al-Ghurabaa (Foreigners), and the Islam4UK, having many supporters. His activity was mostly digital, which confirms once more the contribution of cyberspace to the successful propagation of jihad. He advocated the imposition of Sharia on the United Kingdom, the Islamisation of society, and revenge for all the injustices suffered by Islam (Watson, 2017).

Recruitment

Recruitment is no longer done exclusively by experienced veteran fighters in local training centers, mosques, cultural centers, and other convenient places. This process has been digitized and diversified after the military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq, and the long-term presence of foreign military forces in these areas. Terrorist groups lost their military training bases and tried to survive through cyberspace, which was the new field of their action. Initially, the territorial expansion of ISIS occurred in Iraq and Syria, where it established the Caliphate and then tried to expand digitally by creating a “Cyber Caliphate”. This dual-fronted strategy aimed to reinforce jihad both physically and digitally, broaden the scope of its activities, recruit and mobilize members, and unify Muslims of the diaspora.

The organization strategically employed cyberspace and the ICTs for recruitment, transforming ‘traditional terrorists’ into ‘cyber fighters’, because they can develop their knowledge on the use of traditional means but also their cyber skills (Gunaratna, 2016, pp.84-93). Digital tools facilitated decentralized operations, allowing recruiters to disseminate jihadist narratives, network, mobilize, and coordinate offline and online terrorist activities. Digital recruitment had not fully replaced the need for physical presence but also demonstrated greater efficiency within a shorter timeframe.

Recruiters are enabled by the homogeneity of virtual environments, where they can isolate potential fighters into private clusters, from counter-narratives and ensure that they will be exposed to the desired ideas, their ideas. The important factors of recruitment are trust and intimacy to be successful. It has less risk than in the physical world since there is anonymity and encryption methods. The radicalized persons are developing a common digital culture which they apply in their way of communication. Within the realm of online recruitment, several specific methods are employed. These include the dissemination of digital materials, engagement in chat rooms and online forums, maintaining websites and communication platforms, leveraging social media, and even using animations and video-games to attract younger potential fighters.

ISIS focused on new members with specific skills, exemplified by the release of videos of Abu Omar Al Baghdadi. In these videos, titled ‘A Billion Muslims Support the Islamic State’ and ‘Promise to Allah’, Al Baghdadi asked for active public support by Muslims through the publishing of relevant messages, photographs, and videos on social media from his supporters (McCants, 2015). The above also aimed at the recruitment of individuals who possessed skills regarding the use of social media and marketing, to promote the organization’s political agenda (Bloom, 2017, pp.605-608). He called for specialists that could staff the organization’s bases in the Caliphate - ‘judges, as well as people with military, administrative, and service expertise, and medical doctors and engineers of all different specializations and fields’. According to Al Baghdadi, they should not only reflect the practical requirements of establishing this hybrid state but also help underscore its successes (Haroro, 2020).

Social media played a pivotal role in facilitating the recruitment of fighters, with a Brookings Institution study noting more than 46,000 Twitter accounts supportive of ISIS between September and December 2014 (Berger and Morgan, 2015, p.2). Another example was a post on LinkedIn in 2021, from the Media Company Nashir News Group on LinkedIn with opening positions in Caliphate. One of the most important ISIS recruiters was Mehdi Masroor Biswas. He had the role of a ‘jihobbyist’, who supported and promoted jihadism from his Twitter personal account (@ShamiWitness) with thousands of followers without being in direct contact with ISIS (Carter et al., 2014). ISIS’s digital magazines ‘Dar al-Islam’ and ‘Al-Naba’ were responsible for the release of issues regarding the recruitment of supporters to conduct attacks against the organization’s enemies in domestic and foreign locations.

Even within prisons, recruiters use digital tools to coordinate terrorist activities. Prison does not pose an obstacle to terrorist action, but it works like a haven, where like-minded individuals can be successfully recruited. An indicative example was Ab-dullah Basith (Khattab Bhai or Khurasani), who was one of the prime handlers and recruiters of ISIS for the area of India. In 2018, he was imprisoned in Tihar and recruited new fighters via a smartphone (Deshpande, 2020). Examples of successful ISIS digital recruitment were evident in various terrorist incidents such as in Paris (November 2015), London (June and August 2017), and Tunisia (2020).

Operational training

ISIS provided both physical and digital platforms operational training. The operational training in the digital sphere complemented traditional methods conducted in physical training camps, through the establishment of a ‘virtual training camp’. This digital training enabled remote access to training materials and programs for geographically distant supporters. The organization created ‘virtual organizers’ that remotely provided proper information and material to fighters to plan, support, and conduct an attack (Nesser, 2019, p.19). Online training materials encompassed diverse formats such as audio-visual material, digital magazines [(Al-Anfal (Spoils of War, Earnings, Savings, Profits), Haqq, Rumiyah, Huroof (Letters)], training series (Silsilat) and videos, digital technology (global navigation systems, satellite images of the area taken by Street View, or 3D panoramic photos), simulation systems and videogames.

The digital magazines like ‘Al-Anfal’ and ‘Rumiyah’, distributed on encrypted communication platforms such as Telegram, provided detailed information on weapons usage, including biological weapons, knives, vehicle attacks, or making Molotov cocktails made from household items (Al Hayat Media Centre, 2017). Training videos are self-produced by fighters or from media companies and cover instructions for conducting attacks and making conventional weapons. A notable example is ISIS’s video titled ‘You Must Fight Them, Believer of Allah’ where a French-speaking fighter describes ways that knives could be used in attacks and gives instructions on how to make improvised explosive devices by using household items (Loaa, 2016).

However, an emphasis should be on the effective tactic of operational training, ‘gamification’, which was Al Qaeda’s inspiration. ISIS adapted Western-produced videogames (e.g., Call of Duty, Grand Theft Auto, and Hurtlocker) to disseminate its ideological background, tactics, and goals to the players. ISIS videogames were ‘Call of Jihad’, ‘Huroof’ (Letters), ‘ARMA3 3D FPS’, and ‘Salil al-Sawarim’ (The Clanging of the Swords 1, 2, 3, and 4), which achieved significant sales (Tassi, 2014). They created trailers for the videogames and disseminated them from mass-media companies to social media in several non-Arabic languages to ensure a greater impact (Lakomy, 2019, pp.383-406). The fact that a terrorist organization had created a trailer for the promotion of a videogame was quite contradictory and innovative. The videogames served as a means of radicalization and recruitment because the players remained active and dedicated to jihad. Moreover, the players were able to receive proper digital training to conduct terrorist attacks, because videogames offered a kind of simulation. In this virtual battlefield, players could fight the organization’s enemies (internal enemies, Shiites, Jews, etc.) in shoot footage similar to the areas of Iraq and Syria (Fisher and Prucha, 2019, pp.71156).

Strategic communication

Strategic communication via cyberspace offers distinctive advantages, such as its range and scope, creating an almost global digital arena, surpassing other traditional media. This medium offers freedom of expression in a world where its users do not ‘filter’ their ideas and opinions. ISIS’s strategic communication strategy is more successful than other terrorist organizations. It managed to exploit Al Qaeda's communication heritage and utilize digital technology to promote jihad. They transformed a local terrorist organization into a global brand, operating a Western-style business approach.

ISIS’s narratives can be divided into three main themes - political, religious, and social. The political narrative encompasses references to political aspirations, such as the self-proclaimed Caliph Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the vision of the Caliphate, the unity of Muslims, the revenge of opponents, and the broadcasting of their successful activities. The broadcasting of their success offers visibility and publicity, portraying ISIS as a powerful organization and fostering the radicalization of new fighters. Additionally, it includes references to ongoing political topics for the Muslim community, exploiting conflicts in the Middle East and South Africa to symbolically present opponents as ‘enemies of Islam’. The religious narrative centers on promoting radical Islam, framing jihad as the religious duty of all Muslims (Colombo and Curini, 2022, 5). ISIS presented a carefully constructed image of its actions and rhetoric by using a particular vocabulary with many religious and historical Arabic events (Dabiq’s fight, Syria’s conflict, etc.), and Islamic symbols (the black banner from the Abbasids and the seal of Muhammed) for the ‘awakening’ of believers to become fighters (Styszynski, 2016, 171-180). It is a type of religious indoctrination to justify their horrible terrorist actions and sectarian war based on references to the Quran and Sunnah. By presenting itself as the main political and religious authority in the Sunni community, ISIS aimed to succeed in a ‘religious legitimacy’. The social narrative emphasizes the promotion of fighter’s daily life and their operational training. Through this social content, ISIS tried to portray an ideal life within the Caliphate, which could be used to influence the younger audiences, who wish to have more momentous roles and true meaning in their lives.

The goals of ISIS’s strategic communication included religious indoctrination, promotion of Salafism-Jihadism, establishing itself as a religious authority, enhancing reputation, showcasing authority, marketing the Caliphate to enhance migration, constructing a new jihadist identity, fostering the unity of Muslims, boosting online and offline attacks, and instilling global terror. These goals and the strategic use of media in multiple languages underscore ISIS’s comprehensive and sophisticated propaganda campaign aimed at advancing its political agenda and recruiting supporters across linguistic and cultural boundaries.

They used the below means to promote their narratives: digital radio (Al-Bayan, A'maq Ikhbariyya), newsletters (Al Naba), religious sermons, songs (Salil al-sawarim, province of Aleppo, Deadly Arrows, The Killings of Shiites, My Ummah, Dawn Has Appeared), online books and manuals (Islamic State 2015, Anarchist Cookbook), jihadist online groups and websites, and digital magazines (Dabiq, al-Naba, Dar al-Islam, Konstantiniyye, Istok, Rumiyah, Voice of Hind) (Winter, 2015a, pp.6-15; Ajroudi, 2020). They also disseminated their digital content in various languages through various audio-visual production companies, such as Αl-Hayat Media Center, Al-Furqan Islamic Heritage Foundation for Media Production, Amaq News Agency και Central Media Department (Siboni et al., 2015, pp.127-140). They created songs to glorify jihad, its actions, and its fighters. Abu Yaseer released two songs online, ‘Salil al-Sawarim’, which had more than 1.5 million views, and ‘The Words Are Now about Action and Hence Words of the Sword’ with 3.5 million views (Fisher and Prucha, 2019, pp.71-156).

It is worth mentioning that for ISIS, it was crucial to have the support of the Arab-speaking people in the digital world for several reasons. Firstly, the leaders and most members of ISIS are Arabs, and the affiliated groups of the organization are in Arabic countries. Therefore, the group is trying to expand its territory authority in Arab-inhabited lands. Moreover, the official language of the organization is Arabic, and its religious and ideological system is based on the Arab Sunni community.

ISIS’s videos were based on Hollywood-style imagery (western cultural standards), conforming to Western cultural standards, incorporating cinematic motifs, use of Islamic music, and having a duration of less than five minutes (Wood, 2019). The organization had a massive production of audio-visual material from 2013 to 2016, with more than forty videos. The videos can be categorized into those featuring more ‘emotional and tender images’, and those depicting ‘brutal content and horrific images’. The former paradoxically promoted quite emotional and tender images contrasting the organization’s jihadist rhetoric and political objectives. Some videos showed soldiers taking care of kittens or eating products of Western origin. The intended perspective was that the fighters were not just terrorists but defenders of peace and prosperity as well. The publication of warm images of ISIS fighters holding animals in their arms was a good trick for radicalization. The latter category was designed to instill fear in the audience and reinforce the radical behaviour of fighters. It contained elements of raw violence, such as kidnapping and executions of individuals, battlefield scenes, explosions, etc. These images were accompanied by provocative and threatening statements by fighters (Yeung, 2015, pp.1-18). There are many videos with brutal content and horrific images [E.g.: James Foley (2014), Lend Me Your Ears (2014), Flames of War I, II (2014 & 2017), Paris Has Collapsed (2015), The End of Sykes-Picot (2014), There is no life without jihad (2014)].

The digital footprints of ISIS’s supporters prove the transformation of the traditional form of terrorists into social media influencers. ISIS exploited the power of social media to disseminate their narratives, recruit sympathizers, provoke violence, and facilitate decentralized, interactive, and broad-spectrum communication (Sinai, 2015, pp.196-210). Fighters’ social media accounts provided essential information and references for the organization’s activity (Shori Liang, 2017). They could express their radical ideas anonymously to a wider audience without any filter or restriction to freedom of expression. Platforms such as YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Ask.fm, TikTok, WhatsApp, Snapchat, Telegram, Rocket.Chat, Riot, TamTam, Tor, and Tumblr were essential for their strategic communication (Winter, 2015a, p.4). In 2022, 14% of ISIS’s propaganda was on decentralized web services and over 8,500 URLs containing ISIS propaganda content on more than one hundred platforms (Tech Against Terrorism, 2022). Twitter and Facebook proved particularly useful for ISIS because they enabled the organization to disseminate its messages to a worldwide audience with little to no censorship.

ISIS employed three significant tactics on social media to disseminate its narratives. The first involved ‘Hashtag or Textual Hijacking’, which involves utilizing hashtags and serves the purpose of digitally grouping users and guiding them toward malicious content. The ‘Event Crashing’ capitalized popular events to gather essential information from the targeted accounts. The tactic of ‘Persona Poaching’ entailed creating troll accounts using real social media profiles for anonymous propaganda. Typical examples are the 2014 FIFA World Cup, the successful military intervention of ISIS in Mosul, the referendum on the independence of Scotland from Great Britain, and the Paris attacks.

In addition, ISIS used digital tools that limited the tracing of digital fingerprints, such as Tor, Tails, DuckDuckGo, StartPage, PhotoMe Beta, ExifTool, MetaNull, Jitsi, and JustPaste. It, Silent Circle, etc. The application ‘The Dawn of Glad Tiding’ was an innovative action that allowed users to maintain their digital presence on social media. Simultaneously, it provided them with access to personal data and allowed other malicious users to exploit the data. The application enabled its users to reactivate their accounts within a minute and continue posting unhampered (START Report, 2014; Marks, 2014). In this way, they were able to bypass the security barriers of social media. This application was available in the Google Play Store for a brief period in 2014, with thousands of accounts having access to it. The application was removed from Twitter in June 2014, deactivating thousands of accounts that were supportive of ISIS (Berger and Morgan, 2015, p.25).

Funding

ISIS stands out as one of the most financially endowed terrorist organizations in the annals of terrorism. It managed to establish a state (Caliphate), intertwining religious and political tenets rooted in the Islamic economy and governance systems (Neumann, 2016a, pp.83-84). Its economic ascendancy paralleled territorial expansion, capitalizing on vital resources within its occupied lands and leveraging economic support from members via propaganda-driven initiatives (Woertz, 2014, pp.1-5).

During its initial phase, ISIS garnered substantial revenue through bank robberies and the control of oil and natural gas fields. The organization’s occupation of Eastern Syria’s oil fields of Eastern Syria facilitated the sales, including transactions with the Syrian government (BBC, 2014). By 2014, it controlled 60% of Syria’s and 7% of Iraq’s oil reserves (Neumann, 2016b, p.88). Additional funding sources encompassed possession of foreign assets, ransom from high-profile abductions, donations from wealthy supporters and members, and the sale of looted artifacts from archaeological monuments (Gerges, 2021). Contributions from foreign fighters, the imposition of a tax of faith (zakat), money laundering through online gambling (emoney, ekash, PayPal, etc.), and the trafficking of drugs and arms were important sources of funding (Lazopoulos Friedman, 2016, pp.1068-1098).

In the subsequent phase, ISIS used cyberspace to increase its economic resources. The dark web served as a clandestine platform for the illicit trade of arms and antiquities, capitalizing on limited access, encrypted software, and anonymity (Weimann, 2016, pp.40-44). Notably, artifacts from the archaeological site of Palmyra ended up in London through Turkey, fetching exorbitant prices in private collections via eBay, Skype, WhatsApp, and Kik (Shabi, 2015; Harmansah, 2015, pp.170-178). Another example is that the Al-Hayat Media Center disseminated links on the dark web via Telegram, fostering over 700 channels with more than 10,000 viewers by March 2016 (Shori Liang, 2017, pp.11-20). ISIS has employed crowdfunding campaigns on various online platforms to raise money for its activities. These campaigns may be disguised as humanitarian efforts or other seemingly legitimate causes to attract donations.

The organization’s supporters and members fulfilled their religious obligation and supported operational activities by paying the tax of faith digitally (Woertz, 2014, pp.1-5). While not strictly digital, it has also utilized informal money transfer systems, known as ‘hawala networks’ (Mowatt-Larssen, 2016). In addition, it conducted illegal online transactions of cars, guns, houses, travel documents, and tangible assets, mostly to foreign fighters with the use of cryptocurrencies like Bitcoins (Stern, 2016, pp.195-214). Furthermore, its hackers conducted cyberattacks on financial systems and individual accounts to collect financial resources. There have been cases where ISIS engaged in online extortion, threatening individuals, or organizations with cyberattacks unless they pay a ransom in cryptocurrency.

Online matching

The pivotal involvement of women within ISIS is evident through their integral roles in conducting terrorist activities and fostering recruitment and radicalization. The orchestrated process targeting the radicalization and recruitment of women from Western societies, primarily through social media, communication, and dating platforms, is called ‘online matching’. This trend was introduced by ISIS, aiming to identify women suitable as partners for its fighters in the Caliphate by the promise of a better life (Binetti, 2015, pp.2). During their communication, they used a coded vocabulary, such as the use of words “Umm” (mother) and “Zora” (dawn) on Twitter, to avoid being noticed on social media by counterterrorism (Stern and Berger, 2016, pp.59-61). Upon becoming ISIS members, women were precluded from engaging with technological means to prevent the dissemination of images contradicting the prescribed narrative of the organization (Binetti, 2015, 6).

Recognizing the essential role of women in the building and preservation of the Caliphate, ISIS tailored its propaganda to appeal specifically to this demographic. They promoted marriage and childbirth, contributing to the growth and expansion of the Caliphate but also the restoration of Sharia. Women assumed responsibility for the upbringing of their offspring and the spreading of radical ideology to cultivate authentic and dedicated supporters, including future members of ISIS (Vale, 2019). They used phrases such as ‘You are the hope of the ummah and the ummah will not rise without your help’ (Winter, 2015b). Dabiq magazine featured articles expounding on the purportedly ideal life of women in the Caliphate and their ability to support the organization’s actions (Shori Liang, 2017). Their content of propaganda did not display elements of raw violence but, in favor of softer elements such as pink and purple backgrounds and scenic images (Pearson, 2016, 19).

Despite accusations of misogyny and horrendous acts against women, ISIS succeeded in recruiting them through a multifaceted approach. The push factors of radicalization and recruitment encompassed several elements. Primarily, individuals sought a renewed sense of identity and belonging following social exclusion and marginalization exacerbated by the proliferation of Islamophobia. Furthermore, the Caliphate was marketed as a haven where religious women were established and could lead a fulfilling life irrespective of their national or religious affiliations. A significant reason was ISIS’s promotion of the notion that Western society was threatening the Islamic community. Hence, supporters of the organization were obliged to wage war against the West to protect the rest of the Muslims. For example, a woman posted on Twitter that there are only two camps in the world, the one of Islam and the one of the infidels, and nothing in between (Bakker and De Leede, 2015).

When women migrated to the Caliphate, they stayed in a safe house, called ‘central offices’ (maqar). In these central offices, they received proper training, including the manipulation of social media and information systems for recruitment and the propagation of jihad (Spencer, 2015, p.79). Despite initial impressions conveyed through online propaganda of an idyllic life in the Caliphate with promises of luxury, financial stability, security, and the possibility of forming a family, women soon discovered that all were fake (Binetti, 2015, pp.3-6). They could not escape and were forced to remain and to ensure the survival of their families. The ideal society presented on social media served as a ‘deceptive façade’, that served to persuade women to join the organization.

Hacking

The unprecedented expansion of ISIS encompassing technical support, training, and other facets, is underpinned by the collaborative efforts of supporting hacking groups. In parallel with their military operations, ISIS’s affiliated groups strived to reinforce its digital presence. Their members operated independently, as ‘lone operators’ of cyberspace, selecting their targets. It is assumed that ISIS’s hacking groups were able to launch effective and vulnerable cyberattacks against the critical infrastructure of formidable states. These groups were also broadcasting the successful activities of ISIS and maximizing its prestige. Notable hacking groups are the Cyber Caliphate Army, Sons of Caliphate Army, United Caliphate Cyber, Rabitat Al Ansar, Islamic State Hacking Division, Islamic Cyber Army, Fighter Moeslim Cyber Caliphate, Anon Terror, Cyber Caliphate Ghosts, and Anshar Caliphate Army (Alkhouri et al., 2016, pp.3-18).

The Cyber Caliphate Army was an early hacking group of ISIS, and its representative was Junaid Hussain, also known as Abu Hussain al Britani. Hussain, a British hacker, emerged as a leading figure in the field of ISIS propaganda, recruiting hackers to conduct cyberattacks. His vision was the establishment of a ‘digital Caliphate’ through the training of corresponding ‘digital fighters’ (Alkhouri et al., 2016, p.4). Notably, he conducted a cyberattack against US Central Command’s Twitter and YouTube accounts, replacing users’ profile images with masked fighters, accompanied by messages such as ‘Je suis ISIS’, ‘Cyber Caliphate’, and ‘I love you ISIS’ (EFSAS, 2018).

The Sons of Caliphate Army released a 25-minute video titled ‘Flames of the Supporters’ (Flames of Ansar), depicting pictures of Mark Zuckerberg, the founder of Facebook, and Jack Dorsey, the founder of Twitter, covered with bullet holes (Nance and Sampron, 2017, pp.69-74). This release was prompted by the deplatforming of thousands of the organization’s accounts by these platforms. The group claimed responsibility for hacking 10,000 Facebook accounts, 150 Facebook groups, and over 5,000 Twitter accounts (Manusaga, 2016).

The United Caliphate Cyber constituted the organization’s digital operational arm and conducted several cyberattacks for nearly a year targeting individuals, military entities, and corporate accounts to leak data to the Internet. Digital campaigns, such as #KillCrusaders, #Gazwa:Reloaded, #Op_Gaz_Chamber, and #Demolishing_Fences, were initiated, soliciting supporters for attacks against specified targets (Nance and Sampron, 2017, pp.27, 75).

The League of Supporters (Rabitat Al Ansar) released a video in May 2015 titled ‘Message to America: from the Earth to the Digital World’, utilizing hashtags #ISIS and #CyberAnsar. This video proclaimed their intent to wage cyberwar against the USA and its allies (Liv, 2019, pp.1-35).

Table 1. ISIS’s ‘Digital Jihad’

|

Radicalization

|

Cyber-Caliphate, target groups, social mapping, profiling, social media,

chat rooms, online preachers and preaching, online magazines, and videos.

|

|

Recruitment

|

Digital material, audiovisual

material, development of lone wolves, digital jihad, books, manuals.

|

|

Operational training

|

Development of cyber and

traditional operational skills, live training without the use of physical

presence, digital classrooms, high-quality videos, online magazines, and

gamification (video games).

|

|

Strategic Communication

– Propaganda

|

high-quality audiovisual

material with short duration, digital campaigns, religious sermons, websites,

fora, communication platforms, encryption and mapping applications, social

media, hashtag campaigns, persona poaching, video crashing, event crashing,

emotional/violent videos, digital radio, books, songs, media companies for

its production and promotion.

|

|

Funding

|

Payments of taxes of faith

through cyberspace, sponsorships, donations, charities with digital

campaigns, cyberattacks on financial systems, use of cryptocurrencies, and

sales on the dark/deep web.

|

|

Online Matching

|

Social media, dating apps, and

communication platforms.

|

The Cyber Caliphate Ghosts released a video that declared cyberwar against Western societies. In addition, it published a list on Telegram containing personal information regarding students and professors at the University of Michigan (Lee, 2016). Finally, the Anshar Caliphate Army conducted cyberattacks on 160 websites, 110 Facebook accounts, and 20 Instagram accounts in various countries, within the context of the #OpTheWorld campaign. All the above-mentioned hacking groups developed hacking capabilities and conducted a series of malicious cyber activities, in contrast with other similar terrorist organizations.

Conclusion

This article undertakes an examination of ISIS’s activities within cyberspace via the ‘Digital Jihad’. The empirical data encompasses basic operational activities such as radicalization, recruitment, operational training, strategic communication-propaganda, funding, hacking activities from the organization’s affiliated groups, and online matching. ISIS embraced a modern digital culture and combined its physical and digital operational activities. Paradoxically, despite the organization’s hard stance on matters of religion and the envisions of an Islamic Caliphate - it fully adopted every technological innovation and followed the current modernization to ensure its expansion and preservation, to gain the desired publicity, to promote its political goals, to have effective operational activities and to instill fear and terror to its opponents. Along with this, it strived to shield its identity and ideological background from the ‘corruption’ of Western ideas and values. The modus operandi applied by ISIS will serve as a legacy for future terrorists.

A comprehensive review of the above empirical evidence leads to some important conclusions. In the early 2000s when terrorist organizations such as ISIS disseminated propaganda that referred to events against the Muslim community, it is noteworthy that the fighters were often of elementary school age. Thus, it is not rational that they would seek revenge for their grievances during the operations of the Global War on Terror, because they did not have a personal experience. These fighters were recruited through digital means and lacked military experience. Their motivation primarily stemmed from an expressed desire to participate in the jihadist struggle of ISIS. Moreover, ISIS stands out as the initial terrorist organization that, alongside establishing a ‘physical Caliphate’, created a ‘digital Caliphate’. The digital domain provided supporters a means to participate unhampered in the latter if they could not join the former. Their operational training no longer demanded physical presence but only ‘cyber-fighters’ that received real-time training or watched relevant digital audiovisual material. The growth of the organization’s capital inflow and the funding of its terrorist actions took place unconstrained via cyberspace. Despite its territorial losses due to 2017 military interventions and local conflicts with rival terrorist organizations, ISIS remains a persistent threat to global security. Adapting to contemporary social-political conditions, ISIS extensively integrated ICTs into its operational activities.

In order to effectively counter the multifaceted operational activities of terrorist organizations such as ISIS, it is imperative to conduct a comprehensive analysis of their digital activities and trace their evolution through the extensive use of ICTs. The countermeasures require focused efforts including technological means, strategic communication tactics, and effective censorship, to defame and disorganize terrorist activities. The achievement of these goals relies on the collaborative efforts of states, international organizations, as well as the private sector, including social media platforms, cybersecurity companies, and various organizations. Only through such effective collaboration and the development of specific measures will terrorist activities be diminished. A crucial aspect of this effort is the deconstruction of radical religious ideas that lead to terrorism through the creation and widespread dissemination of effective counter-narratives in the digital sphere.

Cite this article:

APA 6th Edition

Kapsokoli, E. (2023). Isis’s Digital Jihad. National security and the future, 24 (3), 39-66. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.24.3.2

MLA 8th Edition

Kapsokoli, Eleni. "Isis’s Digital Jihad." National security and the future, vol. 24, br. 3, 2023, str. 39-66. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.24.3.2

Chicago 17th Edition

Kapsokoli, Eleni. "Isis’s Digital Jihad." National security and the future 24, br. 3 (2023): 39-66. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.24.3.2

Harvard

Kapsokoli, E. (2023). 'Isis’s Digital Jihad', National security and the future, 24(3), str. 39-66. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.24.3.2

Vancouver

Kapsokoli E. Isis’s Digital Jihad. National security and the future [Internet]. 2023 [pristupljeno: DD.MM.YYYY.];24(3):39-66. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.24.3.2

IEEE

E. Kapsokoli, "Isis’s Digital Jihad", National security and the future, vol.24, br. 3, str. 39-66, 2023. [Online]. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.24.3.2

Literature:

1. Ajroudi, A. (20 May 2020). It sounds like BBC’: ISIS seeks legitimacy via ‘caliphate’ radio service. Al-Arabiya News.

2. Al Hayat Media Centre. (January 2017). The flames of justice. Rumiyah, no.5.

3. Alkhouri, L., Kassirer, A. and Nixon, A. (2016). Hacking for ISIS: The emergent cyber threat landscape. Flashpoint.

4. Bakker, E. and De Leede, S. (2015). European female jihadists in Syria: exploring an under-researched topic. ICCT.

5. BBC. (2 August 2014). Syria Iraq: The Islamic State militant group.

6. Bećirević, E. (2018). Extremism Research Forum: Montenegro Report.

7. Berger, J.M. and Morgan, J. (2015). The ISIS Twitter Census Defining and describing the population of ISIS supporters on Twitter. The Brookings Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World Analysis Paper, no.20.

8. Binetti, A. (2015). A new frontier: human trafficking and ISIS’s recruitment of women from the West. Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security, pp.1-8.

9. Bloom, M. (2017). Constructing expertise: terrorist recruitment and “talent spotting” in the PIRA, Al Qaeda, and ISIS. Studies in conflict and terrorism 40, no.7, pp.603-623.

10. Briggs, R. (2011). Radicalisation, the role of the internet, pages 1-20. Institute for Strategic Dialogue.

11. Carter, J.A., Maher, S. and Neumann, P.R. (2014). #Greenbirds: Measuring Importance and Influence in Syrian Foreign Fighter Networks. ICSR, pp.7-30.

12. Chapsos, Ι. (2010). Suicide Terrorism. Journal of European Security and Defence Issues 1, no.3, pp.28-35.

13. Cockburn, P. (2014). The Jihadis return. Metaixmio Publications. (In Greek).

14. Colombo, M. and Curini, L. (2022). Discussing the Islamic State on Twitter. Palgrave Macmillan.

15. Cronin, A.K. (2015). ISIS is not a terrorist group. Foreign Affairs 94(2), pp.87-98.

16. Deshpande, Α. (19 September 2020). Hyderabad-based Islamic State handler operates from Tihar through a smartphone. The Hindu.

17. EFSAS. (July 2018). Cyber-radicalization: Combating terrorism in the digital era.

18. Fisher, A. and Prucha, N. (2019). A Milestone for “Islamic State” Propaganda: “The Clanging of the Swords, part 4”. Religion and transformation in Contemporary European Society 14, pp. 71-156.

19. Gendron, A. (2017). The Call to Jihad: Charismatic Preachers and the Internet, Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 40, no.1, pp.44-61.

20. Gerges, F.A. (2021). ISIS: a history. Princeton University Press.

21. Gunaratna, R. (2016). Countering Daesh Propaganda: Action-Oriented Research for Practical Policy Outcomes. The Carter Center.

22. Harmansah, O. (2015). ISIS, Heritage, and the spectacles of destruction in the Global Media. Near Eastern Archaeology 78, no.3, pp.170-178.

23. Haroro, J.I. (2020). The charismatic leadership phenomenon in radical and military Islamism. Routledge.

24. Helland, C. (2000). Religion-Online and Virtual Communities. In Religion on the Internet: Research Prospects and Promises, eds. Jeffrey K. Hadden and Douglas E. Cowan, JAI Press, pp.205-223.

25. Hoffman, B. (2017). Inside Terrorism. 3rd ed. Columbia University Press.

26. Kadivar, J. (2020). Daesh and the Power of Media and Message. Arab Media & Society 30, pp.1-28.

27. Kapsokoli, E. (2019). The Transformation of Islamic Terrorism through Cyberspace: The Case of ISIS. In Proceedings of the 18th European Conference on Cyber Warfare and Security, eds. Ti-ago Cruz and Paulo Simoes, University of Coimbra.

28. Kapsokoli, E. (2021). “Cyber-jihad in the Western Balkans”, National Security and the Future 22, no.3, St. George Association.

29. Kapsokoli, E. (2023). “Cyberterrorism: A New Wave of Terrorism or Not, Ferrag, M.A., Kantzavelou, I., Maglaras, L. and Janicke, H. (eds.) Hybrid Threats, Cyberterrorism, and Cyberwarfare, 1st Edition, CRC Press book, Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, chapter 4.

30. Lakomy, M. (2019). Let's Play a Video Game: Jihadi Propaganda in the World of Electronic Entertainment. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 42, no.4, pp.383-406.

31. Lazopoulos Friedman, L. (2016). ISIS’s Get Rich Quick Scheme: Sell the World’s Cultural Heritage on the Black-Market Purchasers of ISIS-Looted Syrian Artifacts Are Not Criminally Liable under the NSPA and the McClain Doctrine in the Eleventh Circuit. University of Miami Law Review 70, no.4, pp.1068-1098.

32. Lee, M. (19 November 2016). Michigan State University Hacked, Student Data Stolen. Forbes.

33. Liv, N. (2019). United Cyber Caliphate. Interdisciplinary Center (IDC).

34. Loaa, A. (28 November 2016). Video: ‘You Must Fight Them O Muwahhid’, ISIS tutorial on killing disbelievers.

35. Looney, S., Parker, J. and Conway, M. (2017) “Online Jihadi Instructional Content: The Role of Magazines” in Conway, M., Jarvis, L., Nouri, L. (eds.) Lehane O Terrorists' Use of the Internet, IOS Press, pp.182-193

36. Manusaga, S. (23 February 2016). Apple vs FBI: Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, John McAfee and more taking stands. Los Angeles Times.

37. Marks, P. (25 June 2014). How ISIS is winning the online war for Iraq. New Scientist.

38. McCants, W. (2015). The ISIS Apocalypse: The History, Strategy, and Doomsday Vision of the Islamic State. St. Martin's Press.

39. McCauley, C. and Moskalenko, S. (2008). Mechanisms of political radicalization: pathways toward terrorism, Terrorism and Political Violence 20, no.3, pp.415-433.

40. McNair, B. (2008). Introduction to Communication Policy. Katarti Publications. (In Greek).

41. Meleagrou-Hitchens, A. and Kaderbhai, N. (2017). Research perspectives on online radicalisation, a literature review 2006-2016, International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation.

42. Mowatt-Larssen, K. (2016). Black Hawala: Confronting ISIL on the Financial Front. American University American University National Security Law Brief 6 (2), pp.58-80.

43. Nance, M. and Sampron, C. (2017). Hacking ISIS: the war to kill the cyber-Jihad. Skyhorse Publishing.

44. Nesser, P. (2019). Military interventions, jihadi networks, and terrorist entrepreneurs: how the Islamic State terror wave rose so high in Europe, CTC Sentinel 12, no.3, pp.15-21.

45. Neumann, P. (2016a). Radicalized: new jihadists and the threat to the West. IB Tauris.

46. Neumann, P.R. (2016b). The new jihadists, Islamic State, Europe, and the next wave of terrorism. Diametros Publications. (In Greek).

47. Pearson, E. (2016). The Case of Roshonara Choudhry: Implications for Theory on Online Radicalization, ISIS Women, and the Gendered Jihad. Policy and Internet 8, no.1, pp. 5–33.

48. Provost, F., Dalessandro, B., Hook, R., Zhang, X. and Murray, A. (2011) Audience Selection for Online Brand Advertising: Privacy-friendly Social Network Targeting, Proceedings of the 15th ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery and data mining.

49. Shabi, R. (3 July 2015). Looted in Syria and sold in London: The British antique shops dealing in artifacts smuggled by ISIS. The Guardian.

50. Shori Liang, C. (2017). Unveiling the “United Cyber Caliphate” and the Birth of the E-Terrorist. Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, pp.11-20.

51. Siboni G., Cohen D. and Koren T. (2015). The Islamic States strategy in cyberspace. Military and Strategic Affairs 7, pp.127-140.

52. Silber, M. and Bhatt, A. (2007). Radicalization in the West: the homegrown threat. New York City Police Department.

53. Sinai, J. (2015). Innovation in Terrorists, Counter-Surveillance: The Case of al-Qaeda and Its Affiliates, in Ranstorp, M. and Normark, M. Understanding Terrorism Innovation and Learning, Routledge, pp.196–210.

54. Spencer, A.N. (2015). The hidden face of terrorism, an analysis of the women in Islamic State. Journal of Strategic Security 9, no.3.

55. START Report (2014). The Islamic State of Iraq and Levant: Branding, leadership culture and lethal attraction.

56. Stern, J. (2016). ISIL and the goal of organizational survival in Matfess, H. and Miklaucic, M. (eds.) Beyond Convergence, World without Order, pp.195-214.

57. Stern, J. and Berger, J. (2016). ISIS: The state of terror. Ecco Trade.

58. Styszynski, M. (2016). ISIS’s communication strategy. Przeglad Strategiczny, no.9, pp.171-180.

59. Tassi, P. (20 September 2014). ISIS Uses 'GTA 5' In New Teen Recruitment Video. Forbes.

60. Tech Against Terrorism. (2022). Trends in Terrorist and Violent Extremist Use of the Internet 2022.

61. Vale, G. (2019). Women in Islamic State: From Caliphate to Camps. ICCT Policy Brief.

62. Watson, R. (2017). Has al Muhajiroun been underestimated? BBC News.

63. Weimann, G. (2016). Terrorist migration to the dark web. Perspectives on Terrorism 10, no.3, pp.40-44.

64. Wiktorowicz, Q. (2015) A genealogy of radical Islam, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 28, no.2, pp.75-97.

65. Winter, C. (2015a). The virtual Caliphate, understanding the Islamic State’s propaganda strategy. Quilliam Foundation.

66. Winter, C. (2015b). Women of the Islamic State, a manifesto on women by the Al Khansaa Brigade. Quilliam Foundation.

67. Winter, C. (2017). Totalitarian Insurgency: Evaluating the Islamic State’s in theatre propaganda operations. CIWAG Case Studies 15, pp.6-46.

68. Woertz, E. (2014). How long will ISIS last economically? Notes Internationals CIDOB 98, pp.1-5.

69. Wood, G. (2019). The way of the strangers. Random House.

70. Yannakogeorgos, P.A. (2014). Rethinking the Threat of Cyberterrorism. In Cyberterrorism: Understanding, Assessment, and Response, eds. Thomas M. Chen, Lee Jarvis and Stuart Macdonald, Springer, pp.43-62.

71. Yeung, C. (2015). A critical analysis of ISIS media strategies. University of Salford.